PS In 2003, when Kamala Harris was in a run-off for District Attorney against Terence Hallinan, her campaign manager, a woman named Rebecca Prozan, made a weird gaffe. On Nov. 30, trying to play spy, Prozan sent an e-mail signed “Jeff” to the Hallinan campaign website. She thought she was being slick, but her name appeared at the top.

“Hello, I am a gay man who supports Terence because of his support of medical marijuana. Please tell me how I can help this week. Go Hallinan!!”

Hallinan’s campaign manager, Laurie Beijen, gleefully replied, “Thanks for your offer of help. We are having a campaign rally at Ocean Beach at Judah tonight at 10 PM- midnight. Please come and hold up a sign for Terence. Thanks!!”

On Dec. 1 the still unwitting Prozan e-mailed: “I just got your message and I was too late. Is there anything else I can do this week? I work, so I’m not available during the day or at 10pm on a Sunday. Thanks. Jeff.”

At this point Beijen notified a Chronicle reporter, who informed Prozan that she’d been exposed. “People make mistakes,” was her lame excuse. “I’m on a campaign. I’m just fighting fire with fire… When you’re in a war, you always want to know what the other side is doing.”

In a war, the officer in charge has lieutenants, scouts, sources of intelligence. The general doesn’t put on a mask and try to sneak behind enemy lines. What kind of jive operation was Prozan running? And why would she impersonate a gay man? I’m not a Freudian, but…

The Chronicle described Beijen as “more amused than upset” by Prozan’s duplicity. They quoted her making ze little joke: “It’s too bad she found out. I was going to send her to the zoo tonight.”

She should have demanded an apology on Kayo’s behalf! The gratuitous invoking of sexual orientation and medical marijuana use is the worst sort of stereotyping. Kamala’s claim that she’d run a more efficient DA’s office may well be valid, but it’s undercut by her choice of Rebecca Prozan to run her campaign. And Kayo’s campaign manager lets up when she has her opponent on the ropes.

Original Iago at 850

On my first day as his press secretary, District Attorney Terence “Kayo” Hallinan told me who was who in the office: which lawyers were assigned to which units, who had special expertise, who he had hired during his first term, whose loyalty he questioned, etc. He spoke with special respect and affection for Kamala Harris. “A great hire,” he called her, giving himself some credit for perspicacity. She had been a prosecutor for the Alameda County DA’s office, highly recommended by Kayo’s former Chief Assistant, Dick Iglehart, and by Mayor Willie Brown. He also had high praise for Vernon Grigg, a young African-American he had hired and recently put in charge of Narcotics prosecutions.

In January 2000 there was considerable media interest in a measure to be voted on in the upcoming March election —”Proposition 21″— which would give prosecutors the option of trying defendants younger than 18 in Superior Court instead of the juvenile courts. (Previously such decisions had been up to the judges.) Hallinan had opposed Prop 21 —the only DA in the state to do so. The Assistant DA who had been most heavily involved in the No-on-21 campaign, speaking at rallies and helping draft position papers, was Kamala Harris.

When reporters would call with questions regarding Prop 21, I would give them the option of interviewing Terence or Kamala, who was knowledgable and felt strongly about the subject. She foresaw 38,000 more kids per year, most of them black and Latino, being tried in adult court over the year. Also, Kamala, then 36, was willing and generally available, which Terence was not. (I was learning that about a third of the Assistant DAs really didn’t want to talk to reporters, about a third really did, and the other third would deal with the media if asked, but wouldn’t volunteer.)

One of the first memos I wrote to Kayo praised Kamala Harris for bringing honor to SFDA and advancing a cause he supported.

Reading it now I see I was trying to keep marijuana in the forefront of his consciousness. The note to Seth Rosenfeld, a Chronicle reporter doing a piece about booking procedures, shows how much I had to learn about basic operations at the Hall of Justice.

Two weeks after I started at SFDA, Darrell Salomon became “the number two” —Hallinan’s Chief Assistant. As a young lawyer Salomon had helped Mayor Joe Alioto sue Look Magazine for linking him to the Mafia. In the ’90s he had helped the Fang family acquire the San Francisco Examiner from the Hearst Corp. for the bargain price of minus $66 million (seller pays buyer). Hallinan hoped that Salomon would introduce efficiencies to SFDA that are common practice at successful private-sector firms.

Not long after he arrived, Salomon came into my office and instead of sitting in the chair across the desk, pulled it over so he could sit alongside me and read what was on my computer screen. This was not a man stealing a sideways glance. I swiveled the monitor slightly to make it easier for him to read as I pondered his intent: Dominance gesture? Mafia tradition? Trying to get something on me? Whatever was on the screen was work-connected, rest assured. I was honored to be employed by the city/county of San Francisco and the tough-minded old boxer who had done so much to oppose the Drug War and give people a break here and there.

“You and I have a philosophical difference,” were Salomon’s first words.

“That may be,” I said. “What about?”

“You’re trying to make a star out of Kamala Harris.”

“I can’t make a star out of Kamala Harris,” I said, “She already is a star.”

Thin wisps of smoke started rising from the brow of Darrell Salomon. He said he didn’t want me directing media inquiries about Prop 21 to Kamala because she was planning to run against Hallinan in November 2003. “She has an agenda,” Salomon asserted two or three times. “She has an agenda…” I pointed out that it was February 2000, an exhausting campaign had just ended, and for the next couple of years everybody in the office ought to concentrate on prosecuting crimes without an eye towards an election almost four years away.

I imagined that after working together for a couple of years, Terence and Kamala could sit down and discuss which of them should run in 2003, based on whether he had the energy and desire and whether she had the experience and perspective.

I was like Rip Van Winkle, returning to the world of electoral politics after a 35-year absence. In the early ’60s I had rung doorbells for William Fitts Ryan and William Meyer —pro-disarmament, anti-HUAC Congressmen— and I’d written a speech for Teddy Weiss when he was on the New York City Council. In Y2K I overestimated the importance of “the cause” and underestimated the importance of the ego.

Darrell Saloman told me I didn’t understand politics. “It’s never too early to think in terms of the next campaign,” he said. He said I could learn a lot if I would report to him instead of to Terence. “You could be my eyes and ears in the office,” he said. I ignored his creepy offer and defended my approach to the PIO job. Kamala was spending her week-ends working on the No-on-21 campaign as a volunteer. Also, “The camera loves her” (a quote from KTVU’s Dan Springer). And she thoroughly understood all the ramifications of the law Prop 21 would create. And didn’t it reflect well on Terence Hallinan that his brilliant young African-American protege was looking out for her younger brothers and sisters? Maybe, if they caught her on TV, they’d pay attention.

Darrell sneered at my naivete. I kept going: “And there’s the basic egalitarian principle that those who do the work should get acknowledgment. And it’s the line deputies that reporters want access to, because they know the details of the case…”

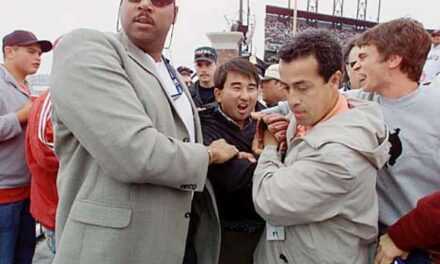

“She’s Willie Brown’s protege!” Darrell blurted, his face gone purple. “He’s f—ing her!” ‘

I said “How do you know? Couldn’t an old gent want to be seen with a beautiful young woman on his arm, leaving the opera?”

He jumped up, shook his finger at me, and said “You direct those reporters’ calls to Terence Hallinan! That’s what he told me to tell you! ”

Later that day, I asked Kamala if she was planning to run in 2003. She said “Not if Terence decides to run for a third term.” She said it would be “unprofessional.” I told Terence, who said I was naive to believe her. He believed the intelligence fed him by Darrell Salomon and some other little Iagos in his employ.

In a memo describing my encounter with his Number Two, I told Terence, “I figure Kamala started speaking out on Prop 21 not because she ‘has an agenda’ but because she has mercy. And if her agenda is to oppose the police state, what’s wrong with that? Darrell said there’s one good thing about her, not you, speaking out against Prop 21: ‘it lowers the risk of alienating the governor, and we may need the governor for money…’ I know you’re very pro-Kamala, and I think it’s reciprocal. That’s why I’m writing to suggest that you rise above seeing her as a rival.”

In a memo describing my encounter with his Number Two, I told Terence, “I figure Kamala started speaking out on Prop 21 not because she ‘has an agenda’ but because she has mercy. And if her agenda is to oppose the police state, what’s wrong with that? Darrell said there’s one good thing about her, not you, speaking out against Prop 21: ‘it lowers the risk of alienating the governor, and we may need the governor for money…’ I know you’re very pro-Kamala, and I think it’s reciprocal. That’s why I’m writing to suggest that you rise above seeing her as a rival.”

Terence said he wanted to handle not only the Prop 21 calls, but all the calls coming in from reporters. He said he felt responsible for the policies and actions being carried out in his name. “I’m the elected official,” he explained. “I’m the D.A. It’s my office. Except for my spokesman, I don’t want anybody going to the media.”

In defense of my approach, I said that the reporters usually want access to the assistant DAs, because it’s the prosecutor arguing the case in court, not the boss— who is most familiar with the course of the trial and the relevant facts. By giving the Assistant DAs leeway to talk, Terence would not only win the reporters’ thanks, he might even catch an occasional break. He knew that I’d been a reporterand had his interests at heart.

“Think of it from Jaxon’s point of view,” I argued, invoking the Chronicle’s indefatigable and highly cynical man at the Hall of Justice, Jaxon Vanderbeken. “Let’s say Braden [Prosecutor Braden Wood] gets an unfavorable verdict but he isn’t allowed to discuss it, so Jaxon has to get you or me to explain what went wrong. He’ll see the explanation as the official party line and all he’ll want to do is poke holes in it. But if he talks to Braden, who just spent six days in court and put his heart into the prosecution and has an idea about why he didn’t get a guilty verdict, Jaxon might quote his comments and not feel impelled to refute him.”

In my two and a half years at the DA’s office I almost always gave the reporters access to the Assistant DAs and Terence never objected. A policy of nobody-but-the-DA-or-his-press-secretary-speaks-to-the-media was probably one of the efficiencies Darrell Saloman had urged on him

If Kamala Harris was hatching any disloyal plans, I never got wind of them. She was a terrific mentor. I remember her instructing Assistant DA Maria Bee to be much more forceful in prosecuting Douglas Chin, dubbed “Rebar Man” by the media. This was a case that the Hallinan-haters had been publicizing. Ken Garcia of the Chronicle characterized it as an “overzealous attempt by Hallinan’s office to prosecute a Mission District man who went on a crusade to combat prostitution in his neighborhood. Douglas Chin, a.k.a. Rebar Man, a mild-mannered electrical engineer, did a stupid thing for a fine cause. He dropped candy-bar-size metal chunks from a rooftop on the cars of johns prowling for hookers around 19th and Capp streets, where he lives.”

Kamala instructed Maria, in fierce tones: “Show some outrage towards this creep! Tell the jury who he really is —a 46-year-old loner who lives with his mother. At night he sits for hours in the front room —in the dark, in the front room of his mother’s house— looking out at the hookers. A creep! When he’s sufficiently aroused, he puts on gloves and a ski mask and climbs a fire escape onto the roof of the church next door. From the roof of the church he hurls down 9-inch chunks of steel, which he has carefully hacksawed –this man is a creep!– at cars that he assumes are driven by pimps and johns. And he admits that he’s done this ritual hundreds of times! It’s a miracle nobody’s gotten killed!”

Maria gulped and nodded and said, “Yes, thank you, yes, I will…” Kamala’s a hell of a mentor, I thought, and certainly not somebody who wants to see the boss look bad. Far from it… But I couldn’t convince Terence.

Darrell Salomon didn’t last the summer at SFDA. He resigned in response to widespread expressions of dislike that he attributed to Kamala Harris’s organizing skills. Unfortunately, the suspicions he planted continued to grow, and Terence decided to test Kamala’s loyalty. He confided in her some information that, if it were to appear in the press, could only have come from her, he assumed. And sure enough, the info did appear before long in a story by Dennis Opatrny of the Recorder, one of two dailies that covered legal developments in the city and county of San Francisco

The morning Opatrny’s piece ran, Terence summoned me into his office. He was behind his desk, waving the legal tabloid triumphantly, his clinching evidence. “You were wrong to keep sticking up for her! See…”

I knew that Kamala was ambitious. I knew the day might come when she wanted to succeed him as DA and he wouldn’t be willing to yield –but that day was at least two years off. Leaking items to Opatrny of the Recorder didn’t seem like Kamala’s style. I wondered if Terence hadn’t told his secret tidbit of info to anyone else.

The item in the Recorder sealed Kamala’s fate. When she heard that Terence intended to give her a de facto demotion, she gave notice and left SFDA to work for Louise Renne at the City Attorney’s office. On her last day at 850 Bryant I leaned into her office and sang a verse of Red River Valley. “From this valley they say you are going. We will miss your bright eyes and sweet smile…” At lunchtime we threw a party for her —a show of respect and affection that the boss would have to shrug off. When it became known that he was on vacation, the sign-up list for the party got so long that even Kimberly Guilfoyle decided to come. So did Opatrny of the Recorder. Vernon Grigg and I sat on each side of him to impede his quest for anti-Hallinan quotes. Many Assistant DAs didn’t make it back to the office till late that afternoon.

Eventually I learned from Dennis Opatrny that his source for the fateful item had been Lisa Hallinan, Terence’s wife. A handsome blonde woman of about 40, Lisa had reasons of her own for cultivating reporters. She was an unabashed “stage mother” with a daughter from a previous marriage who was trying to make it in Hollywood. (My eventual successor would be brought up from L.A., where he had connections.)