Today —we addicts call it “four twenty,” as in 4/20/13— is sacred because it is the day we can satisfy our craving with the really primo stuff from morning till night. Just knowing that it’s available in good supply provides a mild euphoria. Yes, it’s an escape from reality. Yes, it can result in a lingering hangover, a sense of lethargy. Yes, there may be guilt over time spent unproductively. Yes, after a few days of constant indulgence, tolerance might build up. But rest assured that after a brief lay-off —a day or two will suffice— the thrill will be back, and watching the NBA play-offs will be as groovy as ever.

The regular season is way too long. It used to be 64 games, then the owners made it 82. None dare call it a speed-up (except Frank Bardacke, who said “Capitalism can turn anything to shit.”) Basketball never was a non-contact sport, but it has become increasingly gladitorial. The definition of “charging” induces violent collisions between defensive and offensive players. The cult of the dunk induces knee damage. The bosses don’t care about the longterm health of the young giants in their employ. The dwarfs in the media extol an athlete’s “willingness to play hurt.”

The great Rasheed Wallace announced his retirement this week at age 38 after realizing that his surgically repaired feet could not take more pounding from his six-ten frame. The Knicks —the oldest team in the NBA— will miss him, and so will I and many other admirers. He was honest and funny and a three-time all-star. He could play the post and shoot the three —a tall Sativa who provided laughs and insights. He gave the refs honest feedback and for this they slapped him with technical fouls and kicked him out of games. If Rasheed was falsely accused of committing a foul, and the alleged victim then missed his free throw, Rasheed would say “Ball don’t lie,” a brilliant piece of psychoanalysis pointing to the guilty conscience of the foul-shot misser and the incompetence of the ref.

Early in his career Wallace was hounded unmercifully by the Portland media because he and Damon Stoudamire got busted for marijuana possession driving home from Seattle after a Trailblazers’ game. The team owners discarded Wallace, Zack Randoph and other lads deemed by the media to lack “character,” resulting in many long, losing years for the Rose Garden faithful.

NBA players missed an opportunity to take a stand in support of marijuana —their own drug of choice— when the collective bargaining agreement was renegotiated in 1999. Under the old contract, NBA rookies could be tested randomly for cocaine and heroin; veterans could be tested only if there was reasonable suspicion they were using. There was no provision forbidding marijuana use, and according to Selena Roberts of the New York Times, about two-thirds of the players smoked pot as a post-game analgesic and relaxant. Among those who’d been exposed and humiliated were Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the leading scorer in NBA history (caught with six grams while trying to clear customs at the Toronto airport); Robert Parrish, then the oldest player in the league (and one of the best over the course of his career); Allan Iverson; Marcus Canby; Isaiah Rider… In August ’98 Chris Webber was caught with less than half an ounce in his luggage while passing through the airport in San Juan (costing him his deal with Fila).

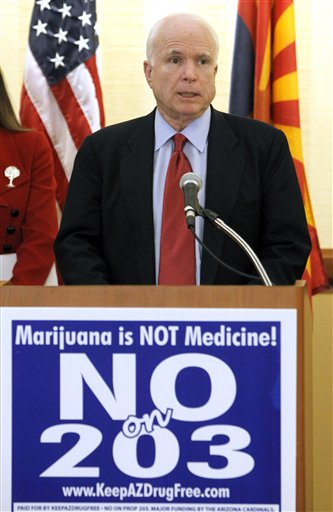

When contract negotiations began in the Spring of ’99, Players Association President Billy Hunter was surprised by the force with which league officials pushed for marijuana testing. Instead of insisting that frequent marijuana use need not be debilitating —Jabbar and Parrish are living proof— and that the players had rights to health, happiness, privacy, etc., Hunter and player representative Patrick Ewing yielded to Commissioner David Stern’s lawyers. They agreed that all players —and coaches and courtside personnel— would submit to peeing in the cup. Hunter told TV reporter Armen Keteyian “We traded it off for something more important. Right now, I don’t quite remember what… We did what we had to do to help enhance the image of our players. The appearance was that many of them engaged in the use of marijuana. The NBA had been pleading or crying for an expanded drug program for years, so we took the high road and acquiesced.”

NBA spokesman Brian MacIntyre crowed at the time, “Kids look up to us. This is the right thing to do.” Poor Patrick Ewing said, “The press asked for it, the commissioner asked for it, we used it during the bargaining session to get something we wanted. We gave it up, that’s it. No sense crying about it.”

According to the agreement Ewing signed, rookies could be tested for mj at any time, but no more than once during training camp and three times during the season. Veterans faced random testing once during the season. First-time offenders would have to undergo counseling. Second-time offenders would be fined $15,000. Subsequent violations would result in five-game suspensions. The L.A. Clippers great small forward Lamar Odom soon tested positive for marijuana twice and had to serve a five-game suspension, and his “tainted” image cost him when next he negotiated a contract… Odom is Rasheed-like in his ability to play a supportive role and not insist on being The Man. You may call it “amotivational syndrome,” I call it “mellow.”

The Doobie Section

Once upon a time Americans could smoke indoors. In the early-to-mid 1970s, the Warriors glory days when Rick Barry and Phil Smith and the underrated Derrek Dickey were building towards that championship season, there was a ramp at one end of the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum known as “the doobie section” to fans who congregated there by the hundreds at half time to smoke joints. You’d see an occasional security guard standing by placidly… Any reader with a recollection of the doobie section is invited to share it. I’m not saying that imposing Prohibition at the Coliseum was causal, but we haven’t won a championship since.

The new owners of the Golden State Warriors, venture capitalist Joe Lacob and Hollywood guy Peter Guber, if not pot-smokers themselves, certainly move in social circles where the herb is commonplace. They ought to urge their fellow owners to drop marijuana testing, and they should do so unilaterally with their own employees. The players association members should refuse to submit to being tested for marijuana — not just on behalf of themselves but also for millions of black and brown and white American cannabis consumers who would be encouraged to stand up for their own dignity at work. (We can expect the players’ agents to function as political prison guards; they’d sooner negotiate for more money than better working conditions.)

Warriors coach Mark Jackson —profoundly humbled since his extra-marital affair was exposed last summer— has turned into a more laid back, effective leader. The Lakers ought to hire Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as head coach. Maybe it’s too late, maybe Jabbar is no longer up to it health-wise, but denying him the job he aspired to all those years was and is a form of blacklisting. The Hollywood Ten never was only ten.

It also may be too late to bring in Rick Barry to teach Andres Biedrins how to shoot an underhand foul shot. Biedrins subtly altered his offensive game to spare himself embarrassment at the foul line and it has done him in. Barry could not only show him the technique, he would provide living proof that shooting free throws underhand is not unmanly.

But I digress… Good luck to the Golden State Warriors on four twenty, here’s hoping that Bogie’s and Steph’s ankles hold up, and may Anthony Randolph, inexplicably cast away, not live up to his Rasheed-like potential in the days ahead.