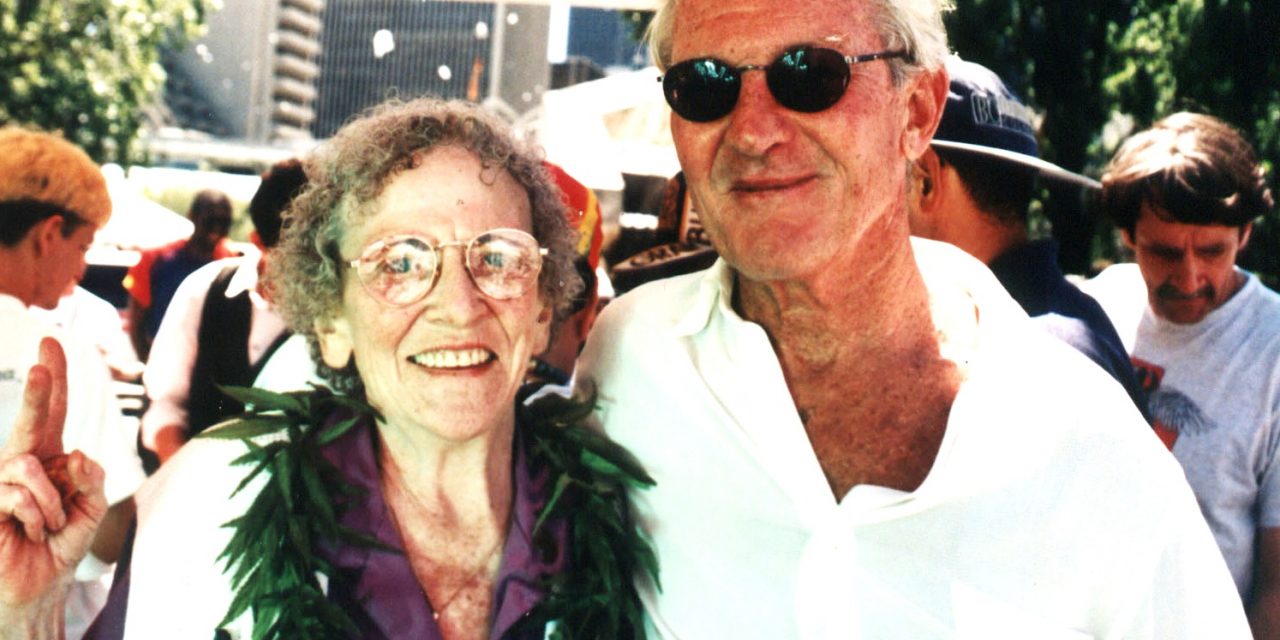

Terence “Kayo” Hallinan died January 16 after a long illness. He was 83. This very informative interview was conducted by Ellen Komp for High Times in the summer of 2001. The photo of Hallinan with Brownie Mary at a rally was taken by David Smith.

By Ellen Komp

Getting arrested six times for protesting almost cost Terence Hallinan his legal career, yet, after stints as a defense attorney and public official, he was elected District Attorney of San Francisco in 1995 and re-elected in 1999. A supporter of Prop. 215, Hallinan favors buyers’ clubs that provide marijuana to patients. He also supports alternative sentencing of drug offenders. Between consulting on a murder case and a union negotiation in his busy office, Hallinan found time to answer a few questions for High Times.

HT: You come from a long line of progressives and fighters for human rights. At what age did you first consider yourself a progressive, and why?

Terence Hallinan: Well, I had five brothers and we were always a big, close family. My parents always discussed everything with us. We’d have these long discussions over the dinner table. I guess it’s a great testament to my parents that all of their children are progressive civil libertarians and nobody has ever disowned their politics, because as kids they got involved in what they were doing.

A big watershed in my life was when my dad defended Harry Bridges and then went to prison. Harry Bridges was a labor leader who fought corruption and exploitation on the San Francisco docks. Bridges incited the ire of powerful West Coast businessmen, and he was smeared first as a tool of England and then as a communist. My dad ran for president of the United States on the Progressive Party ticket from prison in 1952 when I was 16 years old. My family campaigned for him, and we went to the Progressive Party convention where my mother gave a speech. By then, the McCarthy period was on heavily and people were doing things like hammers and sickles on our house.

HT: You’ve said your parents taught you to fight for what you believe in.

TH: My father had a strong view, and my mother agreed with him, that if you wanted to be a progressive you had to be willing to defend yourself; you couldn’t be intimidated, physically, for your views. So my dad gave us boxing lessons and we always had a boxing ring at home. We’d often have friends who were old fighters come and visit.

HT: I understand “Kayo,” the boxing term KO, as in knockout, was your childhood nickname.

TH: Yes. Me and my brothers all had childhood nicknames, and some stuck more than others. Patrick was “Butch,” Michael was “Tuffy,” Matthew was “Dynamite,” Colin was “Flash” and Daniel was “Dangerous.” There was definitely a “boy named Sue” impact to mine. You’d better know how to defend yourself if you’re called “Kayo.”

HT: Did you box in college?

TH: I boxed in high school and college, in the Golden Gloves and in the tryouts for the 1960 Olympics.

HT: Is it true you fought Muhammad Ali, when he was still Cassius Clay?

TH: Yes, in an exhibition match. I remember the incredible speed that he had, and the strength of his punch.

HT: You were still standing at the end of the light?

TH: Yes. [I remember that he added, “It was an exhibition match.” -EK]

HT: That’s impressive enough. Did you make the Olympic team?

TH: No. I had fought Cassius as a light-heavyweight, and since he was also in the Olympic tryouts, I competed as a middleweight. I lost to a guy named George Cooper who later went on to be state middleweight boxing champion and a client of mine.

HT: That’s an interesting way to get a client. Another client of yours was Patty Hearst, before F. Lee Bailey took over her bank robbery case [at her parents’ insistence] in the ‘70s. What do you think of her pardon by President Clinton?

TH: I don’t think she should have gone to prison. Her defense should have been involuntary intoxication. I read her description of when she took her blindfold off in the closet and she looked at her hands, and they were moving. Bailey’s defense, brainwashing, wasn’t a federal defense, but involuntary drug intoxication was. How can a person go through that and end up going to prison?

HT: Speaking of infamous women from the ‘60s, is it true you knew Janis Joplin?

TH: Yeah, I did know her.

HT: You just got such a wistful look on your face. So then you and Bill Bennett both dated her?

TH: I don’t know about Bill Bennett.

[I remember he also lamented that if heroin was legal and regulated as to dosage, Janis might still be with us. -EK]

HT: You were jailed in Mississippi for registering black voters and freed by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. These moves by the federal government have been compared to the federal government exerting authority over states that have voted for medical marijuana. But isn’t there a difference between the two?

TH: Yes. The federal government has an obligation to step in to protect constitutional rights. As far as enforcement of criminal laws, to my mind that’s a local responsibility, because it differs so much from locality to locality. In one place the problem might be crack cocaine, in another it’s amphetamines. The crimes differ from locality to locality, as does the viewpoint of the people. San Francisco’s tolerant attitude towards drugs differs from other places. So local control can be exerted, in one way, through elected district attorneys.

HT: The San Francisco Department of Public Health now recognizes a number of clubs that distribute marijuana to patients with doctors’ recommendations who are legal under California law. How do you think the upcoming Supreme Court decision [US v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Cooperative] might affect those clubs?

TH: I’m not sure how that will work itself out. That case hinges on medical necessity as an exception to federal prohibition against marijuana, and that is a narrow, difficult burden of proof, more narrow than Proposition 215. This Supreme Court is called a compromise court, and maybe they will find some way to leave it up to localities.

HT: Do you think that the struggle to legalize drugs should be framed in a larger context of civil rights, because the War on Drugs is, in effect, the new racism or the new McCarthyism?

TH: Those are aspects of it, but I see [the War on Drugs] as a prohibition, a result of this country’s historical, puritanical tradition to outlaw things it disapproves of. I guess you could say it’s more of a common-sense approach. People have always used drugs. San Francisco’s approach is harm reduction, and I agree with that. All drugs have negative as well as positive aspects, and if people are going to use them, they should learn how to reduce the impact on themselves and society.

HT: So do you think all drugs should be legal?

TH: You need some form of regulation. It’s basically a medical problem. I don’t mind saying I like the doctor’s recommendation idea for using marijuana. I know that a lot of advocates disagree with me, but at least at this time, I think it works. It’s kind of like the 21-year-old age limit for alcohol. It doesn’t work perfectly, it isn’t necessarily right in every situation, it’s easy to get around, but I think a doctor’s recommendation for marijuana keeps a certain rein on it. It means your kids aren’t going to be using marijuana instead of doing their homework at a critical time in their lives, and it means there is some kind of supervision, because every drug has negative effects on certain people. Other drugs should be under a medical umbrella too, like in Arizona.

HT: While serving on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, you favored city-run brothels, saying, “Amsterdam has a red-light district, and I’ve heard good things about their system.” Can you envision a time when a coffee-house model like Amsterdam’s could be the system of regulation for marijuana in this country, perhaps expanding from the medical-cannabis clubs in San Francisco?

TH: Those things kind of develop as they develop. I like the club modality for San Francisco. There are thousands of people who participate in clubs, and an important part of that club movement is the companionship for people who have chronic illnesses that have isolated them and cut them off from their friends. It’s a big support group for people with AIDS and cancer, and the elderly. I’ve seen it. I’ve been there. Sometimes I don’t know which is more important, that pain- and nausea-relieving properties of the marijuana or the camaraderie.

HT: But people who aren’t sick need to socialize, too. Shouldn’t they be able to go to a club to smoke?

TH: Well, given the wording of Prop 215, where it can be for psychological as well as physical reasons, there’s no reason why anybody who feels the need to use marijuana couldn’t use it that way. There are clubs like the Patients Resource Center here with hundreds of members, but there are other clubs of six to eight people who collectively cultivate and share. As far as the questions, shouldn’t anybody be able to smoke marijuana? That question is beyond my expertise.

HT: So you think it should be up to a doctor?

TH: Right now that’s a reasonable regulation. In due time, if the state authorities want to regulate it in a different way, the club model seems not unreasonable to me. I’ve been in Morocco where people go to teashops where they can smoke kif, but you don’t see it out on the street.

HT: Have you been to Amsterdam?

TH: I’ve been to Amsterdam, but it was years ago. I haven’t been there since the coffeeshop movement, although I’ve heard a lot about it. They coffeeshop movement seems like a fine, reasonable approach to me. I don’t have any strong feelings that marijuana is any more dangerous an intoxicant than alcohol. You can’t drink alcohol on the streets; you couldn’t’ be able to smoke marijuana on the streets.

HT: Have you smoked marijuana?

TH: When I was young. I grew up in San Francisco, and I was admitted to the bar in the Summer of Love. I had to smoke marijuana!

HT: How, within the context of the current drug laws, can you address issues such as street-level drug dealing and gang shootings on city streets in a progressive fashion?

TH: Any kind of drug program has to come up with some kind of long-term alternatives: treatment programs, and getting people into jobs and schools. Nobody wants an open-air drug market in their neighborhood, so it has to be treated as criminal. There aren’t any easy solutions. You can put one thousand cops in a bad district and suppress whatever’s going on there until they leave, and then the problems would come back.

One alternative is my first-offenders-of-prostitution program, where johns go to school to learn what prostitution is really about. That school has a two-percent recidivism rate and I use the fees offenders pay to fund the school, plus a program offering job training and other help for women who want to get out of prostitution. About three to four hundred women have taken advantage of it. We concentrate on certain areas and have had success in improving neighborhoods. Prostitution or drugs can never be totally stamped out. All you can do is keep it from becoming a problem. Prostitution has been here as long as the city has been here, so we just keep chipping away at it to keep it from having a negative impact on businesses and neighborhoods.

HT: You created a similar program for small-time drug dealers.

TH: It’s a mentor court program. About 150 people have graduated, and one hundred are going through now. We’ve only had one failure. We’ve had kids not only go to city college and state college, but also get university scholarships. I’m working hard to develop a jobs component to that program.

Proposition 36 is taking effect on July 1, which mandates drug treatment rather than incarceration for low-level offenders. It’s funny because I’ve been bashed for five years for my diversion programs, and now everyone in the state is required to come up with them. I already have more people on drug diversion than the rest of the state, so for me to go from one thousand people to 1,750 on diversion isn’t going to be impossible. It will take more resources, but we will do it. other counties may have only five people on diversion right now, and suddenly they’ll have to place two thousand people each year. They really have a headache.

HT: Have other counties consulted with your office?

TH: No, they haven’t. I was the only DA in the state who supported Prop 36, and it seems a lot of the others are just beginning to reconcile themselves with it.

HT: You have taken some flak for not enforcing California’s “Three Strikes You’re Out” law, except in the case of violent crime. Yet, crime rates are lower in San Francisco than in almost every other county in California. Isn’t that a better measure of a District Attorney?

TH: The traditional approach to judging a DA is the conviction rate. If that criterion remains, even while crime rates go down, prison commitments will go up. I try to be concerned not with conviction rates so much as with results like reducing crime and recidivism. The reality is, the one thousand diversions I’ve overseen are counted against my conviction rate. But we’re turned those lives around, and reduced crime, too. Sometimes it’s hard for people to understand that the critical element isn’t the conviction rate, it’s the crime rate.

HT: But what people want is less crime.

TH: Yes, it is, and I think that’s why I was re-elected.

HT: What makes San Francisco unique, politically speaking?

TH: Why is San Francisco the great city that it is? Why is it such a liberal center? Partly, it’s history. The trade-union movement has a lot of do with it, and the fact that San Francisco was founded by independent, adventurous people—the Gold Rush prospectors, seafarers. But at the same time, it’s the financial center of the West. It has a stock market, and is a magnet for industry and commerce. It’s the hub of the Bay Area, which is the fifth or sixth largest population center in the country. It’s definitely the nerve center of the West Coast.

HT: Would you say it’s true that San Francisco votes against the rest of the country?

TH: I don’t see us as voting against the rest of the country, I see us voting ahead of the country. You can see that in things like our attitude toward medical marijuana. People are willing to try new things here. They aren’t as locked in conventionality. Look who they voted in as district attorney.

HT: Is there truth to the rumor you may run for mayor of San Francisco?

TH: I’m thinking of running for mayor. I will have two terms as a district attorney, two terms as a supervisor, plus two terms on the county committee, so with all those years of holding public office, I naturally think about becoming mayor. There’s so much more potential there for making changes that will make people’s lives better.