After watching Judas and the Black Messiah, I called John Woodford for a reality check. In the summer of 1968 Woodford, then 27, was a staff writer at Ebony magazine in Chicago. His proposals for stories about the Black Panther Party and the anti-war movement had been turned down, so when a job editing the news section of Muhammad Speaks was offered, he thought, “That might be more fun.”

Woodford was not a member of the Nation of Islam, nor was Richard Durham, the editor-in-chief who hired him. “After Malcolm,” Woodford says, “Elijah didn’t want any charismatic young men from within the organization exerting influence on the paper.” Durham had gotten his start in a New Deal writers’ program, then became one of the first Black writers to work in radio, writing a daytime soap opera that drew a huge audience and scripts for the Lone Ranger and other popular series.

Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam (NOI) had to approve Woodford’s hiring. “I went to his house and had a meal with him and didn’t get rejected,” he recalls. He said, ‘All I want you to do is tell the truth, Brother Woodford.'”

There was ample funding because “Muhammad Ali had become a golden goose for a certain little coterie inside the Nation.” A few months after Woodford joined the paper, which had a national weekly readership of several hundred thousand, the NOI invested in a printing plant outfitted with new presses and moved the staff from a small office on 79th Street to the Nation-owned plant. This meant journalists couldn’t smoke during work hours, so one by one, they quit the paper. Durham was ready to leave, Woodford says. “He’d been very tight friends since boyhood with Oscar Brown, Jr. and they had projects going around Chicago. Also, he wanted to work on a movie with Muhammad Ali.” So five months after joining the paper, Woodford became editor-in-chief. The print run soon rose above 400,000. Trucks carried the tabloid to mosques all across the US.

“The old man’s part of the paper was the religious stuff —the centerfold and the two pages on the outside of the centerfold,” Woodford says. “It was intentionally modeled after the Christian Science Monitor in that way. On those two pages were The Teaching of “The Last Messanger of Allah,” columns on dental care, nutrition, and proper behavior of Muslim mothers and wives. In the news section, which varied from 24 to 23 pages, Woodford was free to cover the political scene in all its aspects. The content was strongly anti-imperialist. Woodford used material from correspondents in several US cities and news sources ranging from Liberation News Service to Third World and Socialist print media and political cartoonists.

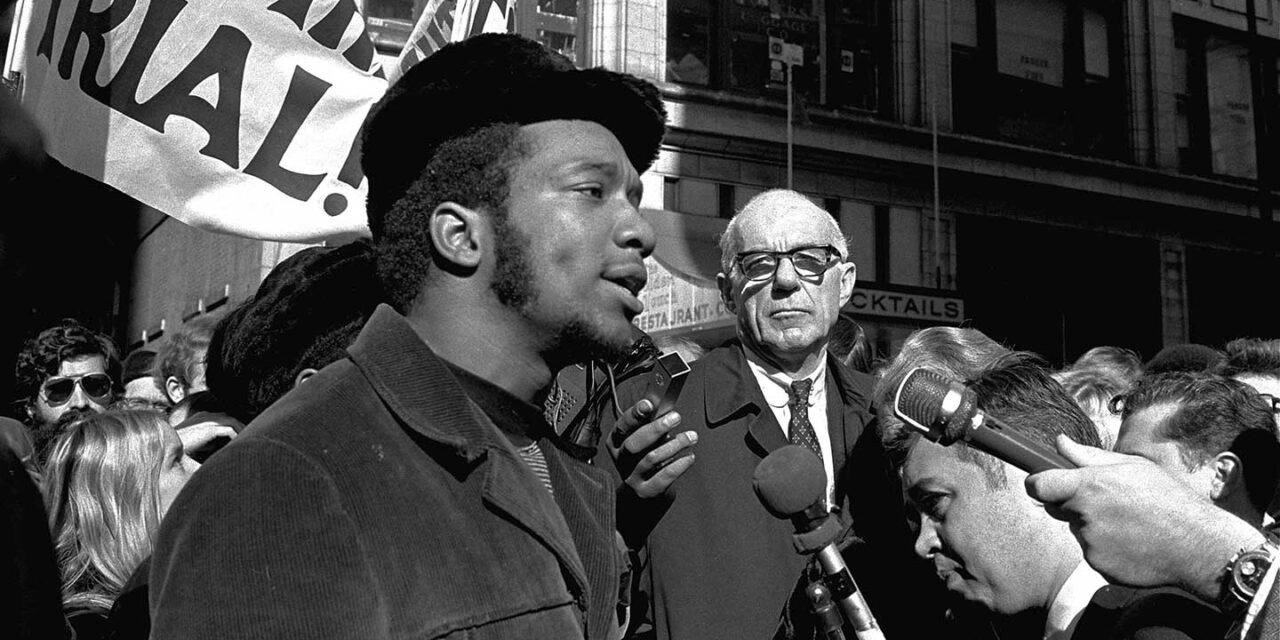

Two University of Chicago grad students who Woodford recalls as “brilliant,” Bob Rhodes and Tom Curtis had organized classes on Marxism-Leninism that were open to local college and high school students. Woodford’s cousin Lynn had joined the Black Panther Party and was attending regularly with her friend, Deborah Johnson, who would become Fred Hampton’s sweetheart. “I think Fred went to some, too,” says Woodford, who audited some of the classes, “although I don’t remember seeing him there. I saw him run a few of the Panther chapter’s political education classes that were required of incoming members. He was into the Red Book [The Quotations of Mao-Tse Tung] and it was more like a religious approach to political education: Maoist slogans. They’d be reading stuff that was relevant to the Chinese peasantry but not to teenagers in Chicago.” Hampton doesn’t wave the Red Book in the movie but he does lead his followers in chanting “I am a revolutionary!” over and over.

Fred Hampton grew up in Maywood, a suburb south of Chicago, about which Woodford says, “People moved there because they didn’t want their kids to grow up where there were gangs. People there had pretty good jobs, union jobs. There were a lot of plants out there. It wasn’t bourgie, but people could have nice little houses. It looked like Detroit used to look when they had jobs in the auto industry. Those high schools were some of the first schools that started getting desegregated and had half-white and half-black basketball teams. Fred was confronting them over swimming pools and beauty queens. He had a real spark to him when it came to confronting racism. He started out as an NAACP youth leader and wanted to do stuff beyond what they were doing. When the Panthers began to get prominent he contacted them and said he wanted to start a Chicago chapter. Bobby Rush had already got the ball rolling, so the two of them got connected. Bobby Rush was a very good guy back then, but he got more and more peculiar once he got into Congress.”

In Judas and the Black Messiah, the betrayer is William O’Neal, a car thief who avoids a prison sentence by becoming an FBI informer. He joins the Panthers’ Chicago chapter and his mechanical skills are much appreciated. (Woodford’s cousin recalls O’Neal as “Mr. Fix-it.”) Woodford remembers O’Neal and a Panther named Louis Truelock (“also an agent, I’m sure”) at a political education class berating people who asked probing questions. “A lot of the kids at the meetings were 18, 17, 16. If their questions were somewhat skeptical, O’Neal and this other guy would scowl at them and say they must be bourgies or pigs. As the movie showed, these ultra types would advocate something close to corporal punishment for members who continued to be somewhat individualistic.”

Woodford says there were eight or nine informers and undercover agents inside the Panthers’ Chicago chapter. “Not hard to sniff out. Like O’Neal in the movie, they’d suggest blowing things up. They’d talk about liberating this and liberating that. They’d say Stalin was a bank robber and that was revolutionary. Those elements are hard to channel and hard to suppress because people want action! And a lot of the young Panthers were from neighborhoods where you had the Disciples and the Black P Stone Rangers running around with guns. So then you had kids with guns who got into shoot-outs with the police. That’s what happened in Chicago —kids who were Panther members but acting on their own got in a shootout and killed a policeman. And that’s when the gloves came off.”

In the movie there’s a composite Black gang called The Crowns. Woodford asks “Why, if they were trying to make an accurate movie, would they create a phony gang? And then they tried to make it look like the Panthers were having some kind of council with them, and even some kind of alliance! That didn’t happen! That’s not what was going on! Sure, they had contact with them, because they hoped to woo away those who weren’t inherent gangsters. But the sane Panthers knew the gangs were poison in their communities.”

Nor was there a successful alliance between the Chicago Panthers and the brown-skinned Young Lords and a synthetic group of poor white folks. The rainbow coalition of lumpen youth shown in the movie was a lefty dream that never materialized.

“Why didn’t they put the Black P Stone Rangers and the Disciples in the movie?” Woodford wonders. “Were they afraid? They glorified these Crowns, in essence. That’s like slipping in a poison pill, politically, because on campuses you still run into faculty people talking about how great it’s going to be when the gangs get politicized and revolutionized. They don’t know what they’re talking about. The Black P Stone Nation ruled their territory like it was Sicily. They would kill anybody for anything.

“People wished they could break the gangs, because as long as the gangs have a neighborhood sewed up, there’s not going to be a lot of progress. They intimidate everyone and they can be used by the police —as they have been throughout history and throughout the world. In Chicago there were Catholic groups that imagined they could convert the gangs so you had a lot of liberals giving money to the Black P Stone nation thinking that they could turn them into progressive forces.” He scoffed, then added. “The Panthers did draw some people who left the gangs.”

A freelance photographer called Woodford early on the morning of December 4, 1969, to say that Fred Hampton was killed and they headed for his apartment. Surpsingly, the scene had not been taped off. Woodford doesn’t think the FBI ordered his assassination, although their informant, O’Neal, facilitated it by drafting a floor plan of Hampton’s room. “It was the Chicago cops,” says Woodford. “Because there had been that shoot-out and a kid had killed a cop. They weren’t going to sit back and let the FBI tell them what to do. And that particular tactic is not one favored by the FBI.”

Woodford’s cousin Lynn was heavily involved in the Panthers’ free breakfasts for children program and the medical clinic. He generalizes: “That was the Panthers’ nature: one element wanting to do good, community-building progressive things, and the others who were into adventurism. A lot of the Panthers were anti-gang but others wished they could be like the gangs only stronger. You had that kind of tension, that split going all the way up high. Bobby Seale and Sam Napier and others wanted to build a revolutionary political party. Eldridge and others worshipped the notion of militant action. In every chapter they had this split.”