By Fred Gardner February 2, 2014 The fact that people of color are punished disproportionately by drug prohibition is now widely acknowledged in the United States. Just last week the New Yorker quoted President Obama stating: “Middle-class kids don’t get locked up for smoking pot, and poor kids do. And African-American kids and Latino kids are more likely to be poor and less likely to have the resources and the support to avoid unduly harsh penalties.”

Still unacknowledged, however, is the role that African Americans have played not as victims but as leading opponents of prohibition. This being Black History Month (I knew her when she was Negro History Week) O’Shaughnessy’s is honoring some men and women whose contributions to the abolitionist cause have been underappreciated or overlooked. Starting with…

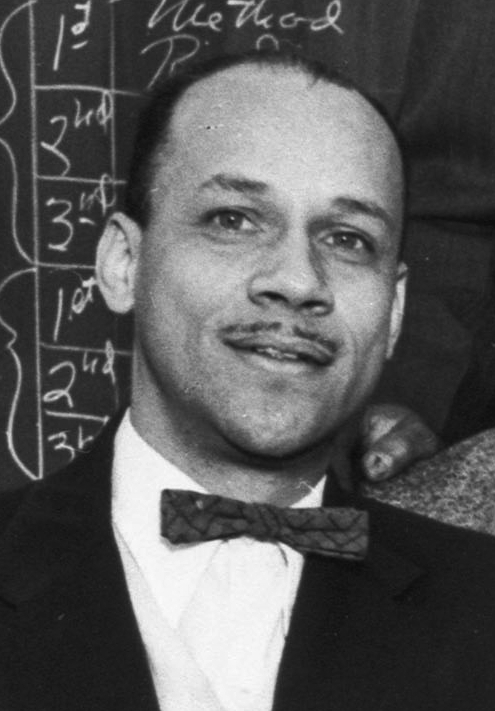

James A. Washington: The Judge Who Recognized Marijuana Use as a “Medical Necessity”

It was a decision by Washington, D.C. Superior Court Judge James A. Washington in the case of United States v. Robert Randall that led to the federal government creating an “investigational new drug protocol” back in the Jimmy Carter era. The case was tried over the course of two days in July, 1976. Here are the facts as recounted by Judge Washington:

“The government has established, and the defendant has not attempted to refute, that on or about August 21, 1975, police officers in the course of their normal duties noticed what they believed to be cannabis plants on the rear porch and in the front windows of defendant’s residence… A warrant was issued and a search of the premises conducted on August 23, 1975. Several plants and a dried substance later identified as marijuana were seized and defendant’s arrest followed.

“At trial, the government’s evidence demonstrated that the substance seized at defendant’s residence was marijuana, possession of which is prohibited by D.C. Code Section 33-402, thus establishing all the elements of the crime charged. Moreover, defendant admitted that he had grown the marijuana in question and that it was intended for his personal consumption. He further testified that he knew that possession and use of this narcotic are restricted by law.

“Defendant nonetheless sought to exonerate himself through the presentation of evidence tending to show that his possession of the marijuana was the result of medical necessity. Over government objection of irrelevancy, defendant testified that he had begun experiencing visual difficulties as an undergraduate in the late 1960s. In 1972 a local opthalmologist, Dr. Benjamin Fine, diagnosed defendant’s condition as glaucoma, a disease of the eye characterized by the excessive accumulation of fluid causing increased intraocular pressure (IOP), distorted vision and, ultimately, blindness.

“Dr. Fine treated defendant with an array of conventional drugs, which stabilized the intraocular pressure when first introduced but became increasingly ineffective as defendant’s tolerance increased. By 1974, defendant’s IOP could no longer be controlled by these medicines, and the disease had progressed to the point where defendant had suffered the complte loss of sight in his right eye and considerable impairment of vision in the left.

“Despite the ineffectiveness of traditional treatments, defendant during this period nonetheless achieved some relief through the inhalation of marijuana smoke. Fearing the legal consequences, defendant did not inform Dr. Fine of his discovery, but after his arrest defendant participated in an experimental program being conducted by opthalmologist Dr. Robert Hepler under the auspices of the United States Government.

“Dr. Hepler testified that his examination of the defendant revealed that treatment with conventional medications was ineffective, and also that surgery, while offering some hope of preserving the vision which remained to defendant, also carried significant risks of immediate blindness. The results of the experimental program indicated that the ingestion of marijuana smoke had a beneficial effect on defendant’s condition, normalizing intraocular pressure and lessening visual distortions.”

A Case of First Impression

Randall’s attorney John Karr recalled in an interview with your correspondent, “Judge Washington had been dean of the Howard University Law School before his appointment to the bench and I knew him to be extremely intelligent and compassionate. A non-jury trial was fine with me….

“Judge Washington was very careful. After the prosecutor had conducted his examination and I had conducted the cross-examination, he would conduct his own inquiries. It was apparent that he had read all the material we had put together on the history of marijuana as medicine. In his decision he referred to the 1937 Congressional hearings that led to the Prohibition, and a number of recent studies and reports.”

“This is a case of first impression in this jurisdiction,” wrote Judge Washington in his decision, “one which raises significant issues. Consequently, the Court recognizes its responsibility to set forth clearly and in some depth its understanding of the applicable law.”

Citing case law, Washington concluded that “the common law recognizes the defense of necessity in criminal cases… where the actor is compelled by external circumstances to perform the illegal act.” He listed three exceptions. The necessity defense cannot be used when “1) The duress or circumstance has been brought about by the actor himself; 2) The same objective could have been accomplished by a less offensive alternative which was available to the actor; or 3) The evil sought to be averted was less heinous than that performed to avoid it.”

The first two exceptions clearly don’t apply in U.S. v. Randall, wrote Washington:

“While the exact cause of defendant’s glaucoma is unknown, neither the government nor any of the expert witnesses has suggested that the defendant is in any way responsible for his condition. Similarly, no alternative course of action would have secured the desired result through a less illegal channel. Because of defendant’s tolerance, treatment with other drugs has become ineffective, and surgery offers only a slim possibility of favorable results coupled with a significant risk of immediate blindness. Neither the origin of the compelling circumstances nor the existence of a more acceptable alternative prevents the successful assertion of the necessity defense.

“The question of whether the evil avoided by defendant’s action is less than the evil inherent in his act is more difficult. It requires a balancing of the interests of this defendant against those of the government. While defendant’s wish to preserve his sight is too obvious to necessitate further comment, the government interests require a more detailed examination.

“One of the oldest recognized drugs, marijuana was not regulated in the United States until the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required that the presence of marijuana be indicated on the labels of products of which it was a component. The modern prohibition began in 1937, in response to primarily economic pressures without significant inquiry into its effects on users.

[Washington’s footnote 21 stated: “Liquor manufacturers and distributors, still recovering from the effects of Prohibition, were interested in eradicating the potential competition from a drug often used for recreational purposes. In addition, criminalizing marijuana simplified the task of eliminating the competition for jobs during the Depression posed by the principal users of the drug, Mexican migrant laborers.]

“The 1970 Controlled Substances Act continued the prohibition of the use of marijuana, but a Presidential Commission was appointed to study its effects. Pending receipt of this report, marijuana was classified as a non-narcotic and although its use was still prohibited, the penalties were considerably reduced, with first offenders being discharged conditionally. The District of Columbia law, however, was not changed, and retains the narcotic classification based on the 1937 Uniform Narcotics Act.

“Medical evidence suggests that the prohibition is not well founded….

“Reports from the President’s Commission and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare have concluded that there is no conclusive scientific evidence of any harm attendant upon the use of marijuana. According to the most recent HEW study, research has failed to establish any substantial physical or mental impairment caused by marijuana. Reports of chromosome damage, reduced immunity to disease, and psychosis are unconfirmed; actual evidence is to the contrary.

“Furthermore, unlike the so-called hard drugs, marijuana does not appear to be physically addictive or to cause the user to develop a tolerance requiring more and more of the drug for the same effects. The current HEW report also notes the possibility of valid medical uses for this drug…

“The Court finds that this defendant does not fall within the third limitation to the necessity defense. The evil he sought to avert, blindness, is greater than that he performed to accomplish it, growing marijuana in his residence in violation of the District of Columbia Code. While blindness was shown by competent medical testimony to be the otherwise inevitable result of defendant’s disease, no adverse effects from the smoking of marijuana have been demonstrated…”

Judge Washington could have ended his decision at this point, but he went on to assert its applicability to other necessity-defense cases. He projected and refuted an argument that would deny the necessity defense based on the literal wording of the DC Code section, which makes no reference to extenuating circumstances. He also discussed whether a defendant should have to prove necessity “beyond a reasonable doubt” and concluded that “by a preponderance of the evidence” was sufficient.

As John Karr put it, “Judge Washington made an effort to find for Randall in every important way.”

Add Recollections from Karr

“Randall came to me through Alice O’Leary, who was an employee of a client of mine at the time, a company called The American Theater. Her story was very touching: ‘My boyfriend has this problem. He’s been busted for growing marijuana on our back porch on Capitol Hill and he’s going blind from glaucoma.’ So I said ‘Okay, bring him in…’

“He told me his very interesting story. So I called a Dr. Brown either at NIH or NIMH and said, ‘What’s current on the use of marijuana as a medicine?’ And he said there were three programs ongoing that NIH knew about. One, I think, in Alabama; one in North Carolina; and one out at the Jules Stein Institute [UCLA]. He said one involved a THC solution delivered intramuscularly; one program reduced it to a pill taken orally; and the one in California was doing it by smoking marijuana.

“So I called the people in North Carolina and I think it was Alabama and they said that their results were very mixed. But Dr. Hepler at UCLA said ‘I got this program going and it looks like a real winner.’ So we sent Randall out to UCLA and Hepler tested him.

“He had no money for the defense. In fact, we never got paid for this. It may have been Alice who put together enough money for the trip. She was the real driver in this thing because she was very concerned about him. Anyway, he went out there for about 10 days and Hepler said ‘It’s a winner.’ I asked Hepler if he would come and testify. We advanced the money for that, I think it was 13 hundred bucks but it didn’t matter because at this point we were all excited about the case… Sure enough, he came and he was a terrific witness.

“There were some amusing moments in the trial. I remember the delivery of one of the plants from the FBI storeroom to the courtroom, wrapped as if it was a gift from a florist. It reminded me of a revue by the old comedy team, Olsen and Johnson, which began with a hotel bellhop crossing the stage and calling out ‘Plant for Mrs. Jones. Plant for Mrs. Jones.’ At the end of each act he would reappear and the plant would have gotten larger and larger and larger…The FBI agent carefully unwrapped the plant, which was now withered, and the prosecutor asked him to roll a joint from it, which he did. This was to prove that it was a usable amount of marijuana…

“At one point I asked my contact at NIMH, Dr. Brown, whether there was a program to get him marijuana legally. And he said you’ve got to get an ‘Investigational New Drug’ approval from the FDA. We called FDA and they sent us the forms and we helped Randall fill them out and send them back and eventually an Investigational New Drug license was issued. And for I don’t remember how long, Randall would show up at Morton’s Drug Store in the 300 block of Pennsylvania Avenue Southeast, three blocks from the Capitol of the United States, and pick up his weekly supply of marijuana. Which looked like an olive-drab pack of cigarettes with a band around it saying ‘Property of the United States of America.’ I remember it vividly because it was just so perfect.

“I called FDA and was told that it was grown in Mississippi and processed and packaged in North Carolina, where all the cigarettes are processed and packaged…”

Too far ahead of his time

Attorney Paul Smollar, who worked with Karr on U.S. v. Randall, recalls: “As a memento, Bob took two cigarettes out of the first pack he received from the government, removed the marijuana, and framed the papers —one for each of us to commemorate our victory in court…’ Medical necessity’ was then a new argument. It had been argued before in criminal cases, but never in connection with marijuana. John is a very creative thinker and an excellent trial lawyer. And he had a good working relationship with Judge Washington. They respected one another. Judge Washington was not only very bright, but he was willing to make a decision that might be unpopular or might be on the leading edge of the law. His decision for Randall was far ahead of its time.

Some 35 years after Judge Washington found for Randall, attorney Robert Raich framed a “medical necessity” argument on behalf of the Oakland Cannabis Buyers Club in a case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court. Raich was unaware of Judge Washington’s decision in support of Randall. “I wish I had known about it,” he told us. “It was scholarly, well-reasoned and well written. I would have incorporated it… I wish we had more such judges these days.”

Judge James A. Washington died in 1998 at the age of 83. His obituaries made reference to his five-year stint in the War Division of the Justice Department, joining the Howard faculty in 1946, work he did as a lawyer in connection with Brown v. Board of Education and other cases leading to the end of public-school segregation in 1954, and a terrible fall that confined him to a wheelchair for the last 20 years of his life. His decision in U.S. v. Randall recognizing a marijuana user’s medical-necessity defense was too far ahead of its time to be recognized as a signal achievement.