In the spring of 2005 the U.S. Supreme Court denied Angel Raich and Diane Monson the right —established by California voters in 1996— to obtain and use marijuana for medical purposes. Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy, two of the five justices who had always advocated limits on federal power, in this case made a War-on-Drugs exception to their “principles.”

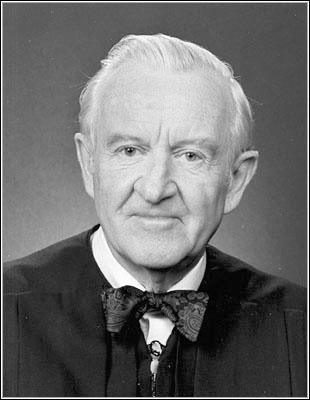

John Paul Stevens, who wrote the majority opinion, was joined by Kennedy, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer. Scalia wrote a concurring opinion trying to justify his apostasy.

Several months later Justice Stevens issued a very unusual public apology for the opinion he had written in the Raich case. Addressing the Clark County, Nevada, Bar Association, Stevens acknowledged that his votes in four cases decided in the previous Court session would cause real harm to large groups of people. “In each I was convinced that the law compelled a result that I would have opposed if I were a legislator,” he revealed.

“…The fourth case in which I was unhappy about the consequences of an opinion that I authored presented the question whether the use of locally grown marijuana for medicinal purposes pursuant to the advice of a competent physician may be punished as a federal crime.

The uncontradicted evidence in the record indicated that marijuana did provide important therapeutic benefits to the two petitioners, that no other medicine was effective, and that without access to that drug one of the petitioners may not survive.

“Moreover, their cultivation and use of marijuana for health reasons was perfectly lawful as a matter of California law. I have no hestiation in telling you that I agree with the policy choice made by the millions of California voters, as well as the voters in at least nine other States (including Nevada), that such use of the drug should be permitted, and that I disagree with executive decisions to invoke criminal sanctions to punish such use.

“Moreover, as I noted in a footnote to our opinion, Judge Kozenski has chronicled medical studies that cast serious doubt on Congress’ assessment that marijuana has no accccepted medical uses.

“Nevertheless, those policy preferences obviously could not play any part in the analysis of the constitutional issue that the case raised. Unless we were to revert to a narrow interpretation of Congress’ power to regulate commerce among the States that has been consistently rejected since the Great Depression of the 1930s, in my judgment our duty to uphold the application of the federal statute was pellucidly clear.”

Justice Stevens didn’t bat 1.000 but we sure miss him now. —Fred Gardner