\

By Fred Gardner

Fiorello LaGuardia was the mayor of New York City when Howard Zinn was growing up in Brooklyn during the Great Depression. Zinn admired LaGuardia and in the end would have important things in common with him. LaGuardia had flown bombing missions for the U.S. Army over Italy during World War One. Zinn flew bombing missions over occupied France in World War Two. Both men would come to reconsider the worth of those missions. Both would spend their lives speaking for people whose voices hardly got heard.

Zinn had written his PhD dissertation on LaGuardia’s years as a Congressman representing the tenement dwellers of East Harlem. (LaGuardia served in Congress from 1917 through 1933, minus his stint in the Army and two years as President of the New York City Board of Aldermen.)

LaGuardia in Congress, published by Cornell University Press in 1959, established Zinn’s reputation as a historian. It debunked the prevailing textbook image of the 1920s. Its themes were encapsulated in an essay, “LaGuardia in the Jazz Age,” which Zinn published in The Politics of History (Beacon, 1970).

“In the United States, the twenties were the years of Prosperity, and Fiorello LaGuardia is one of its few public figures who suspected to what extent that label was a lie,” Zinn asserted.

“In the United States, the twenties were the years of Prosperity, and Fiorello LaGuardia is one of its few public figures who suspected to what extent that label was a lie,” Zinn asserted.

Nor did LaGuardia mistake the twenties for “a time of quiet isolation from foreign affairs,” Zinn wrote. “The United States was established as a dominant power in the Caribbean having purchased the Virgin Islands during the war, possessing a naval base in Cuba, and exercising such control over the Republic of Panama, Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic as to make them ‘virtual protectorates.’ American influence in the Far East extended from the Aleutian Islands to Hawaii and across the western Pacific to the Philippines.”

LaGuardia opposed sending 5,000 U.S. troops to Nicaragua in 1927 to uphold a government subservient to U.S. lumber and fruit interests. “The protection of American life and property in Nicaragua does not require the formidable naval and marine forces operating there now,” La Guardia declared. “Give me 50 New York cops and I can guarantee full protection.”

Zinn wrote that LaGuardia did not see the 1920s as a time of “national political consensus, when a general mood of well-being softened political combat.” Angered by Rep. Fred Vinson of Kentucky’s reference to New York’s “Italian bloc” of voters, LaGuardia “denounced the drastic restriction of immigration and particularly the ‘national origins’ method of determining quotas… The restriction bills were ‘unscientific,’ LaGuardia charged, the ‘result of narrow-minded-ness and bigotry’ and ‘inspired by influences who have a fixed obsession on Anglo-Saxon superiority.’”

By 1937, when Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act, LaGuardia was in his fourth year as mayor of NYC. His nemesis, Vinson of Kentucky, was the Treasury Department’s key ally in pushing marijuana prohibition through the House Ways and Means Committee. Vinson conducted a hostile interrogation of the only witness who understood and strongly opposed prohibition, Dr. William Woodward of the American Medical Association. When the Act came before the full House, instead of explaining its provisions, Vinson recounted Harry Anslinger’s “reefer madness” testimony as undisputed fact.

The question of whether the American Medical Association supported the Marihuana Tax Act was answered thus by Vinson: “Our committee heard testimony of Dr. William Wharton —sic—who not only gave this measure his full support, but also the approval from the American Medical Association which he represented as legislative counsel.” The Act passed on a voice vote and was enacted into law in September of 1937. Fred Vinson, brazen liar, went on to become Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Marijuana prohibition might not have sailed through Congress if Fiorello LaGuardia had still been a member in 1937. The federal ban was based on false facts that no one in Congress questioned, but which LaGuardia recognized as baloney —notably that marijuana is addictive and leads to insanity and violent crime. In 1938 LaGuardia, as mayor, assigned the New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM) to investigate the premises of marijuana prohibition. A blue-ribbon committee of 31 scientists was assembled. Physicians from the city Department of Hospitals supervised clinical research involving 77 patients.

“My own interest in marihuana goes back many years,” LaGuardia wrote in a foreword to the committee’s report,

“to the time when I was a member of the House of Representatives and, in that capacity, heard of the use of marihuana by soldiers stationed in Panama. I was impressed at that time with the report of an Army Board of Inquiry which emphasized the relative harmlessness of the drug and the fact that it played very little role, if any, in problems of delinquency and crime in the Canal Zone.*

“The report of the present investigations covers every phase of the problem and is of practical value not only to our own city but to communities throughout the country. It is a basic contribution to medicine and pharmacology. I am glad that the sociological, psychological, and medical ills commonly attributed to marihuana have been found to be exaggerated…

“The scientific part of the research will be continued in the hope that the drug may prove to possess therapeutic value for the control of drug addiction.”

In other words, the NYAM investigators —and Mayor LaGuardia himself— were hip to the harm-reduction potential of marijuana as a substitute for hard drugs!

A key chapter of the report by Drs. Samuel Allentuck and Karl Bowman, “The Psychiatric Aspects of Marijuana Intoxication,” was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in September 1942. It specifically refuted the Federal Bureau of Narcotics characterization of marijuana as an addictive drug that led to insanity.

An exhaustive investigation into the extent of use by New Yorkers was conducted by a Police Department squad— “two policewomen and four policemen, one of whom was a Negro,” according to Dudley Schoenfeld, MD, who described their findings in the LaGuardia Committee Report. (Read some remarkable excerpts here. Guaranteed to blow your mind!)

While on duty the squad actually ‘lived’ in the environment in which marihuana smoking or peddling was suspected. They frequented poolrooms, bars and grills, dime-a-dance halls, other dance halls to which they took their own partners, theatres —backstage and in the audience‚ roller skating rinks, subways, public toilets and parks and docks. They consorted with the habitués of these places, chance acquaintances on the street, loiterers around schools, subways, and bus terminals. They posed as ‘suckers’ from out of town and as students in college and high schools.”

The full Report, The Marihuana Problem in the City of New York, was published in 1944. Its conclusions, verbatim:

• Marijuana is used extensively in the Borough of Manhattan but the problem is not as acute as it is reported to be in other sections of the United States.

• The introduction of marijuana into this area is recent as compared to other localities.

• The cost of marijuana is low and therefore within the purchasing power of most persons.

• The distribution and use of marijuana is centered in Harlem.

• The majority of marijuana smokers are Blacks and Latin-Americans.

• The consensus among marijuana smokers is that the use of the drug creates a definite feeling of adequacy.

• The practice of smoking marijuana does not lead to addiction in the medical sense of the word.

• The sale and distribution of marijuana is not under the control of any single organized group.

• The use of marijuana does not lead to morphine or heroin or cocaine addiction and no effort is made to create a market for these narcotics by stimulating the practice of marijuana smoking.

• Marijuana is not the determining factor in the commission of major crimes.

• Marijuana smoking is not widespread among school children.

• Juvenile delinquency is not associated with the practice of smoking marijuana.

• The publicity concerning the catastrophic effects of marijuana smoking in New York City is unfounded.

Although the LaGuardia Committee provided evidence and documentation in support of its findings, the Report was ignored at the federal level —as would other painstaking commission reports by government agencies and the medical establishment in the decades to follow.

In 1973 the New York Academy of Medicine reprinted the Report with a foreword by Raymond Schafer, the former governor of Pennsylvania, who had been appointed by President Richard Nixon in 1970 to chair a commission on “Marihuana and Drug Abuse.”

*The Canal Zone Papers

The U.S. Army conducted a serious study of soldiers using marijuana in Panama in the 1920s. These studies were completely ignored by Congress during the debate on Prohibition in 1937. The first study was conducted in April 1925 by a committee chaired by Colonel J.F. Siler of the Medical Corps. A group that included soldiers, doctors, and police officers was observed smoking cannabis.

One officer who participated concluded, “I think we can safely say, based upon samples we have smoked here and upon the reports of the individuals concerned, that there is nothing to indicate any habit-forming tendency or any striking ill effects. All of the statements to the effect that two or three puffs produce remarkable effects are nonsense, judging from our experience.”

The U.S. government printing office published Col. Siler’s report (“Canal Zone Papers,” 1931), which found no evidence that marijuana was addictive or that it had “any appreciable deleterious influence on the individuals using it.”

According to “the Great Book of Hemp” by Rowan Robinson, “Some commanders disagreed with the committeee’s findings and ordered a new investigation in 1929. The surgeon general who directed the inquiry duly reported that ‘use of the drug is not widespread and… its effects upon military efficiency and upon discipline are not great.’ A third investigation, initiated in June 1931, found no link between cannabis and delinquency or morale problems” in the U.S.-run Canal Zone.

The ‘Old Left’ and Mariojuana

The New York Academy of Medicine report includes an example of a “reefer madness” story from the Daily Worker for Dec. 28, 1940. Headlined “Health Advice,” the Communist line on marijuana could easily have come from a William Randolph Hearst paper —minus any racist overtones, of course:

“Smoking of the weed is habit-forming. It destroys the will-power, releases restraints, and promotes insane reactions. Continued use causes the face to become bloated, the eyes bloodshot, the limbs weak and trembling, and the mind sinks into insanity. Robberies, thrill murders, sex crimes and other offenses result… The habit can be cured only by the most severe methods. The addict must be put into an institution, where the drug is gradually withdrawn…”

In the political milieu from which Howard Zinn emerged, marijuana use was looked down on. This disapproval by the “old left” was rooted in ignorance, but it had a practical application. If you were, say, a union organizer, you wouldn’t want to give management spies an excuse to report you to the cops. The fight for higher wages and better working conditions would take precedence over your desire to smoke reefer (which was almost certainly nil, because few Americans, especially white folks, had ever touched the stuff).

The “new left” of the ’60s had a different attitude towards marijuana because millions of people on college campuses and in the military had started smoking it by 1966, and recognized that it wasn’t dangerous. Freedom to smoke marijuana became an auxiliary goal of “the movement” that was primarily aimed at ending racial segregation and bringing the troops home from Vietnam.

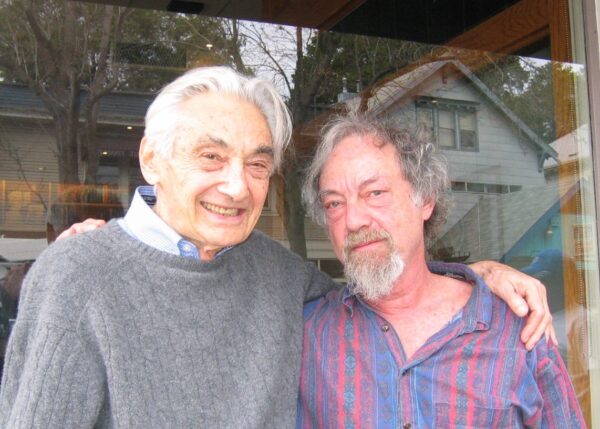

Howard Zinn (left) and Fred Gardner in Berkeley, February 2009. Zinn was staying with a granddaughter, getting away from the cold Boston winter. Photo by Emmy Josephs.