The media had made Terence Hallinan’s leniency a political liability. He counterpunched by publicizing murder cases to the max. Not all his punches landed. Killing the king was “murder most foul” to Shakespeare and Bob Dylan, but most murders are mundane, tawdry tragedies involving poor people and lacking the drama coveted by newspaper and TV assignment editors.

One sunny spring morning, Terence, having been advised that a record number of cases were being tried by the Homicide Division, ordered up an unusual press release in which current prosecutions would be listed “like on a menu” to invite coverage. He told me which Assistant DA was handling which case, and I commenced to get the details and list the trials du jour.

“Seven Murder Cases in Trial This Week,” our press release announced, enticingly. It was “a precedent-setting number,” according to Chief Assistant DA Paul Cummins. Reporters could write about Marcelo Sarmiento, accused of murdering Violetta Ramos, the mother of his child; Sandra Taylor, accused of killing Rexanne Battershell in an arson-homicide at the Kings Hotel on Valencia St.; Donald Lorman, accused of fatally shooting She Mei Lee, a bartender at the Vieni Lucky Spot on Stockton St.; Vincent Tu, accused of killing Kenneth Haramoto in Japantown; Maurice Farr, accused of murdering Anthony Reed; Darrel Langston and Kora Rich, accused of killing Leon Jarvis at Valencia Gardens. (Defendants in a seventh case had gotten a change of venue and were being tried in Los Angeles.)

Our release ended, “District Attorney Terence Hallinan, who has emphasized the prosecution of violent felonies, expressed gratitude to the judges involved in expediting these trials.”

Those murder trials that got coverage had an unusual angle that reporters could play up —the victim was a three-year-old victim, there were multiple victims, the accused is facing a third-strike, the victim was an aspiring chef, a State Senator’s son, an out-of-towner… A 24-year-old woman named Julie Day was raped and strangled by a taxi driver, who then buried her body, which became the object of a well-publicized search. Claire Tempongko was stabbed to death by her ex-boyfriend, Tari Ramirez, who was on the lam after several previous arrests on domestic-violence charges. (“Release when sober,” the police had advised SFDA on their last incident report). Robert Nawi was found guilty of first-degree murder in 2001 of a murder committed in 1987, thanks to the first-ever use of DNA evidence in the San Francisco Superior Court.

“Virginia Lowery has named her killer for you,” Assistant DA Elliot Beckelman had told the jury, referring to the DNA found under the victim’s fingernails. “She held on while Nawi stuck that ice pick into her head. She waited 11 years for the science to catch up to her and 14 years for the police to make an arrest. She held onto them all these years to turn him over to you.”

The murder of Carmel Sanger presented several media-friendly angles, starting with the names of her hair salon, the Pink Tarantula. and her husband, Robert “Skull” Sanger, a 57-year-old biker. To off Mrs. Sanger he had hired Marcos Ranjel, an immigrant from Mexico who had once been a police officer. A first-degree murder verdict against Ranjel was a win for the DA’s office. On the bulletin board outside my office I tacked up a handwritten note congratulating the prosecutor (“Grats to Phil Kearney!”) and a copy of the press release being faxed to the media:

“Four years after hair stylist Carmel Sanger was shot to death in her South-of-Market salon, ‘The Pink Tarantula,’ a San Francisco jury has convicted Marcos Ranjel, 36, of firing the fatal bullet.

“Witnesses at the month-long trial testified that Ranjel walked into the salon on the afternoon of March 5, 1997, asked for Sanger by name, and then shot her in the left eye with a .9 mm Makarov-style pistol.

“The jury deliberated for two days before finding Ranjel guilty of first-degree murder, for which he faces a sentence of life without the possibility of parole. The jury also determined that Ranjel’s motivation for the slaying was monetary.

“Robert Sanger, 57, the ex-husband of Carmel Sanger, will be tried for his role in the murder beginning in early May.

“The case was prosecuted by Assistant DA Philip Kearney and presided over by San Francisco Superior Court Judge Kevin Ryan.

“The jury also found Ranjel guilty of being an ex-felon in possession of a firearm, for which he faces three years.”

The verdict got plenty of ink. I tacked up the news clips, all of which included the word “Tarantula” and/or the phrase “killing-for-hire.”

Two months later Robert Sanger, who had been facing life without the possibility of parole, pled guilty to voluntary manslaughter in exchange for a 10-year sentence. To deflect any appearance of leniency, Phil Kearney explained the disparate outcomes thus: “Talking about killing somebody is one thing; executing a complete stranger with a single shot to the eye is something else entirely.”

President George W. Bush would soon make Kevin Ryan the US Attorney and Phil Ryan would join him as a federal prosecutor.

The Framing of Tennison and Goff

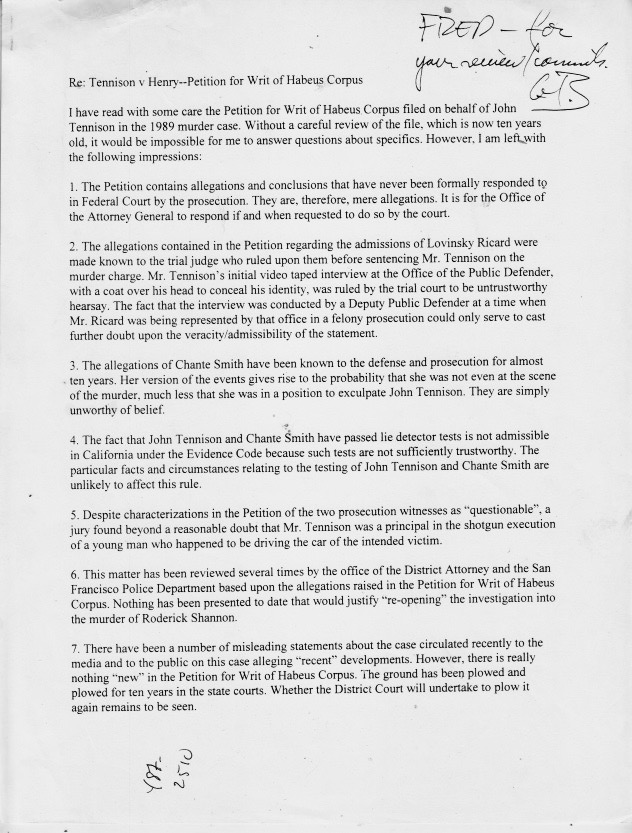

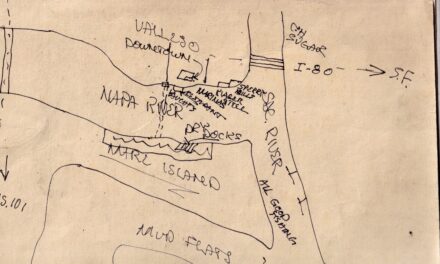

In 1991, when Hallinan’s predecessor was in office, Assistant DA George Butterworth had gotten a conviction against John Tennison and Antoine Goff for the murder of Roderick Shannon. Jeff Adachi, the young public defender who had failed to get Tennison off in ’91, had been filing appeals on his behalf ever since. As of March 2000 Adachi was trying for a fourth time, seeking a writ of Habeus Corpus from the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeal. (Goff had been represented by Barry Melton, a member of Country Joe and the Fish in his younger days.)

In March, 2000, the DA’s office got an inquiry that I summarized in a memo for Butterworth, who was then in charge of gang-related prosecutions. “Reporter Chris Smith from a neighborhood monthly called the SF Observer is inquiring about Goff and Tennison. 1989 gang-related murder. Convicted in ’91, in prison since. ‘Some evidence has become available that would prove them innocent… Talk that the DA will reopen the case… Acccusations that prosecutors concealed evidence.’ Please advise.”

I didn’t realize how familiar with the details of the case Butterworth was. He responded with a lengthy, detailed memo dismissing Tennison’s claim of innocence. The memo concluded, “There is really nothing new in the Petition for Writ of Habeus Corpus. The ground has been plowed and plowed for 10 years in the state courts.”

But after a hearing in November 2000, the 9th Circuit ordered Judge Claudia Wilken to make a “thorough review” of the evidence, and in 2003 that righteous woman ordered Tennison set free.

George Butterworth was a tall, lanky Caucasian who wore Brooks Brothers suits and looked like an aging preppy. His wife was also an Assistant DA. The happy couple commuted to the Hall of Justice from Walnut Creek. On a bulletin board above his desk George Butterworth had neatly tacked up about 60 Polaroid photos of brown-skinned men in orange jump suits —an organizational chart, he explained to me, of San Francisco gangs. It was like a hunter’s wall with trophies on display. I was surprised that Hallinan retained his services, and equally surprised when I read in 2006 that Kamala Harris had appointed him to head the SFDA Homicide Division. Harris told the Chronicle that Butterworth had “a wealth of experience, knowledge and expertise. I have no doubt the city will benefit from that experience.”

Jaxon Van Derbeken, the ace reporter who covered the Hall of Justice for the Chronicle, wrote a piece recalling that Butterworth had successfully prosecuted Tennison and Goff. Van Derbeken explained:

“Both continued to insist they were innocent, and in 2003 U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken reversed Tennison’s conviction on the ground that prosecutors had withheld evidence that could have led to his acquittal. She called Butterworth’s actions in the case ‘troubling.’

“The judge found that prosecutors had not given Tennison’s attorney evidence concerning a secret police payment fund for witnesses or the results of a polygraph examination of one of the girls that cast doubt on her story.

“Prosecutors also failed to tell the defense about two eyewitnesses who contradicted the girls and didn’t reveal in a timely fashion that another man had confessed to the killing after the trial, the judge said.

“One of the girls, Pauline Maluina, said in an interview with The Chronicle in 2003 that she had tried to change her story before the trial, but that neither Butterworth nor police ‘seemed interested in hearing the truth.’

“Then-District Attorney Terence Hallinan did not appeal Wilken’s ruling and after a separate investigation concluded that Tennison and Goff had not committed the killing. With his concurrence, a San Francisco judge declared both men ‘factually innocent.” No one else has been charged with the killing.

“Randolph Daar, an attorney representing Goff in a lawsuit against the city saying he was wrongfully imprisoned, said Harris’ selection of Butterworth as her lead homicide prosecutor was ‘kind of shocking. Here she has promoted a guy whose actions… led to the wrongful imprisonment of two men for 12 years,” Daar said. “Was that on his resume? Did he use Judge Wilken as a reference?'”

After this ran in the AVA a retired SFPD officer commented that Butterworth was “a class act” and the array of photos on his bulletin board was not unique. When Kamala made him head of Homicide, the Chronicle had quoted a colleague calling Butterworth “a brilliant choice… He has more knowledge in the Bayview (sic) than anybody in the office. He has the respect of the Police Department. He has worked closely with federal law enforcement agencies.”

Whatever “knowledge” Butterworth may have had concerning the Bayview district (his forté was the organizational structure and leadership of various gangs), he was totally devoid of empathy with its people. What could he know about 17-year-old JJ Tennison?