My medical problem wasn’t as grave as Bruce Anderson’s (described in the AVA February 28), but I, too, have been impressed by and grateful for the care I received at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus. My friend Steve Heilig, AVA stalwart and longtime director of public health and education at the San Francisco Marin Medical Society, commented online: “Nobody wants to be a patient but if ya gotta, UCSF is a lucky place to land. Always in the top 3 nationally and – public! Ain’t socialized medicine/research/teaching grand?”

How and why and for how long can “socialized medicine” exist at one hospital within a system of for-profit healthcare?

In 1997 I was working at UCSF’s Parnassus Heights campus when “Mission Bay” was but a gleam in Vice-Chancellor Bruce Spaulding’s eye. Developers had been planning the second campus long before Spaulding shared the news with the 10,000-member campus community (faculty and students at the schools of Medicined=, Nursing, Dentistry, and Pharmacy; doctors, nurses, and workers in an array of supportive roles; and a growing number of middle-level managers, making UCSF Medical Center the largest employer in the city. It already had outposts at SF General, Mt. Zion, the VA Hospital, and Laurel Heights, a large campus acquired from Fireman’s Fund to house the burgeoning administration).

A second-year medical student named Alex Papanastassiou broke the Mission Bay story in the October 10 issue of Synapse, the UCSF weekly.

“The selection of an architectural firm to design the 43-acre UCSF Mission Bay basic science research campus will be decided this Sunday, Nov. 2. A small group of business leaders called BALSA (Bay Area Life Sciences Alliance) financed a contest to pick five finalists… The campus will be located along the bay south of Market Street (see illustration on page 12). Campus Planning expects construction to begin in 12 to 18 months and continue for 10 to 20 years. The project will cost an estimated $800 million to $1 billion. Precisely which programs will move to Mission Bay has yet to be decided, but Kevin Beauchamp of Campus Planning estimates that some 9,000 people will work and study at the new site —400 faculty, 2,500 staff, and 6,100 postdocs, grad students and technicians. By way of comparison, the Parnassus campus has 33 usable acres and on a typical day accomodates 15,400 people, including 2,680 visitors, 2,570 patients, 6,550 faculty and staff members, and 3,600 students and postdocs. The new campus will be the largest development in the history of San Francisco after Golden Gate Park and the Presidio, said Clifford Graves of BALSA at a meeting on campus Oct. 28.

“UCSF’s 43 acres were donated by the Catellus Development Corporation, in connection with a 303 acre project that will include open space and land for housing, retail, recreation, and biotechnological and other commercial and industrial development….The architects were guided by UCSF’s Long Range Development Plan, adopted by the UC regents in January, 1997 and a 1,300-page environmental impact statement…

“Spaulding acknowledged the housing concerns of students and junior faculty, and said plans were under way for new housing facilities at Mission Bay. One possibility would be for UCSF to buy or rent residential units to be built on Catellus’s parcel of land. Alternatively, student housing could be bought or built in the neighboring community.'”

In a follow-up story hedded “UCSF and BALSA Forming Partnership to Develop Mission Bay Campus,” Pappanastiou wrote: “Allan Long of Campus Planning expects the formation of the partnership to speed the development of the Mission Bay campus. Because it is a ‘public-private non-profit partnership,’ the business entity will not be subject to the red tape usually involved in UC projects, according to Long. BALSA’s political and financial clout is expected to facilitate the first phase of development…

“Campus Planning has hired the Sedway Group, a real estate consulting firm, to survey the cost and availability of housing within a 1.5 mile radius of Mission Bay. Campus Planning hopes to negotiate for some of the 6,000 units that the developer, Catellus Corp., will build surrounding the Mission Bay campus. Public-Private Partnership Chiron CEO and former UCSF professor William Rutter, and Gap CEO Donald Fisher, formed BALSA in 1996 as a tax-exempt nonprofit public benefit corporation. Clifford Graves, BALSA’s president and former executive director of San Francisco’s Redevelopment Agency, says that BALSA’s goal is ‘to help UCSF make its second campus [at Mission Bay] a reality.’ BALSA facilitated the donation of 43 acres by Catellus for the campus.”

You may recognize the name Donald Fisher. Soon after launching BALSA, he bought Louisiana Pacific’s 350 square miles of redwood forest in Mendocino County to plunder “sustainably.” The Fisher family portfolio was then worth $12 billion. Today it is worth more than $200 billion and includes the Oakland A’s, who will make more money for the Fishers in Las Vegas while bolstering the sustainability of the gambling industry. But back to Papanastassiou on Mission Bay:

“Long says that BALSA is guaranteeing some funds for the initial design work for building IA, and contributing ‘legal and engineering support to negotiate and perform due diligence on the transaction between the University and Catellus.’ This includes such tasks as surveying the land, chemically testing the soil, and going over the title to the land. The partnership’s tasks include designing the Mission Bay campus master plan, fundraising, and promoting governmental and community relations.

“The international design competition funded by BALSA is an example of something that could be done more easily by a private corporation, according to Long, because a private entity does not have to follow regulations that constrain a state institution. A public university can do some things better, too –for example, securing favorable external financing. The partnership can then borrow through the UC treasurer. Thus the land for building IA may be groundleased to the partnership by UCSF at a nominal fee. The partnership will design and build 1A and then may cither turn it over to UCSF or manage the building itself. The most likely route for financing building IA will be the UC treasurer borrowing the money up front through the partnership, probably by issuing bonds, according to Long. This works well because UC is tax exempt as a public institution, and has a sparkling borrowing record.

“The other option, still under consideration, would be for UCSF to lease building 1A back from the partnership.”

(As news about the Mission Bay campus was being revealed by the Chancellor’s office, UCSF was involved in another public-private partnership –a merger with Stanford. The failure of this patently unworkable scheme, which had been strongly opposed by UCSF faculty, was becoming apparent. The collapse of the entity called “UCSF-Stanford Health Care” is one of the totally erased major stories of our time. Financiers at Ernst & Young made millions. California taxpayers picked up the tab.)

Why are there a few great hospitals?

The same day the AVA arrived with Bruce’s paean to UCSF, I heard Chris Hedges interview Gretchen Morgensen, author of “These are the Plunderers” on the Real News Network. Hedges began with this overview:

“The U.S. economy is being held hostage by a small cohort of financiers who run private equity firms –Apollo, Blackstone, the Carlyle Group and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts… Residents of nursing homes owned by private equity firms, for example, experience 10 percent more deaths because of staffing shortages and reduced compliance with standards of care. Private-equity-owned hospitals have created a crisis in the healthcare system. Nursing shortages have contributed to one of every four unexpected hospital deaths or injuries caused by errors. The private-equity firms do not serve patients but profits. They have closed hospitals, especially in rural America. They cut back on stockpiles of vital medical devices, including ventilators and personal protective equipment. In 1975 the U.S. had about 1.5 million hospital beds and a population of about 216 million people. Now, with a population of over 330 million people, we have around 925,000 beds. Fifty-six percent of Americans have medical debt, even though many have insurance, and 23 percent owe $10,000 or more. Emergency room visits – emergency rooms are often run by private equity firms– contributed to medical debt for 44 percent of Americans. At the same time, the health care system, because of this slash-and-burn assault, was unprepared to handle the Covid epidemic, seeing 330,000 Americans die during the pandemic because they could not afford to go to a doctor on time. These private equity firms, like an invasive species, are ubiquitous. They have acquired educational institutions, utility companies and retail chains while bleeding taxpayers of hundreds of billions in subsidies, made possible by bought-and-paid for prosecutors, politicians and regulators.”

While the oligarchs are destroying the US healthcare system, there exist great hospitals like UCSF in all our major cities. Maybe they want to make sure they’ll have access to a first-rate facility in their hours of need. I sent this hypothesis, along with Hedges’s commentary, to a physician who runs the Emergency Room at a university-connected hospital in the Midwest. He replied:

“Hah! I wouldn’t be surprised if the oligarchs were involved but I think the good places are still good because they’re insulated by state money, research grants, political connections and good reputations, and thus shielded from the onslaught of private equity money in medicine.

“Big academic centers are a different model and can prioritize things beyond profit. California takes the best nurses from other states with its high nursing pay and strong union protections. It cuts both ways, though. You routinely have 30-50 people in the ER waiting room because you don’t have enough nurses to maintain the strict 1:4 nurse to patient ratio the union created. Lives have been saved by nurses being able to focus on their small number of patients and lost because there aren’t enough nurses to get people care when they need it.

I think medicine should be a business. How much money a society allocates to medical interventions can’t be a top-down decision. Who deserves dialysis? Who gets the newest million dollar per year what-the-fuckamab for their cancer? Should they get cancer treatment even if they smoked? Or if they’re still smoking? Should we do everything for the debilitated 95 year grandma with no quality of life or the child with anoxic brain injury who will never recover? I have opinions on these things. But so do you. And so does every other person. So trying to make these decisions based on policy, expert opinion, and democratic politics is fraught in so many ways. In the UK you can’t get dialysis over age 65. In Canada there is now more push for euthanasia in cancer than there is for treatment. Is that right? I don’t know. But no one does or can, really, so you need a different way to decide.

If you have a system with actual insurance and actual profit (taking in more than you expend in terms of resources) then you can kind of make priorities. Your bare bones insurance won’t cover fancy new cancer treatments, which is sad but makes sense. Your platinum plan will cover cancer and kidney meds until your last breath at age 110, which is stupid but what some people are willing to pay for. And your healthcare systems will succeed and fail based on how they do the job for the patients they serve.

There will be gaps. But that’s where charity and education should come in. Charity and teaching hospitals funded and staffed by people who care and are ok making less or are in the process of learning. They wouldn’t be perfect. But they’d be better than what we get when we assume that our taxes are helping the poor and sick when in reality that money is being sucked up by the industry.

But that’s a world with “actual” insurance and profit. We don’t have that. We have mandated insurance where industry writes the laws, changes them, abuses the patients and docs, and suffer no consequences or liability. And we have healthcare systems that make money by marking everything up when they bill, then lobby for subsidies, and provide marginal care without recourse because those in charge aren’t liable for any harm they do by providing inadequate care and resources for docs. And that’s without even talking about Pharma and the food industry! (Guess who made it illegal to discharge medical debt in bankruptcy?)

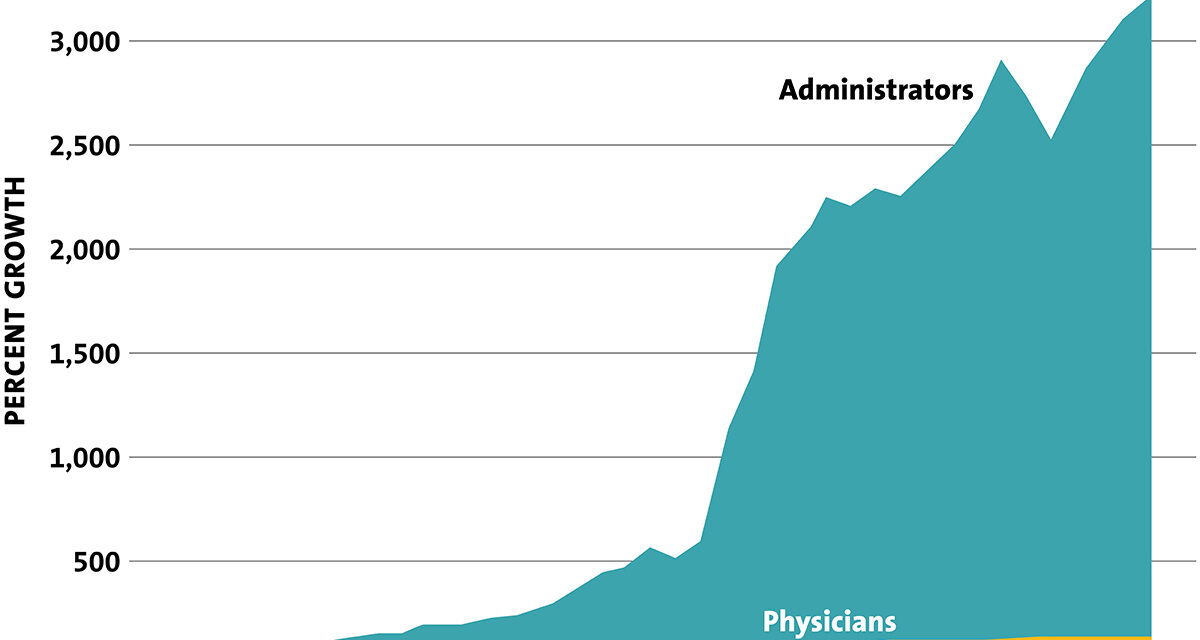

This is the classic graph. I’m confident the last 15 years are worse:

So us good docs hide in academia or the best private places (i.e. Mayo Clinic) and insulate ourselves from the disaster, but it’s eating our world up, too. My hospital makes money by surgery and cancer and cardiac care. Everything I try to do to help all my poor patients is tolerated out of some generosity but mostly fear of lawsuits and bad pr. We need our inpatient beds for the planned knee replacement for the lady with platinum plan insurance and my patient with heart failure will stay in the hallway until they can be patched up enough to be discharged back to the gutter. But if we didn’t do that, given the way things are, there’d be no ER for them to come to.

I don’t see a real policy fix. Private Equity and big industry will eat everything as long as the system is hybrid public-private where they can make the rules and rake in the cash. They can manipulate the law and policy makers with that money as suits them. But I think a fully public system in the states is a dead letter. Even if we did Medicare for all our public sector couldn’t make broadly accepted priorities and it’d turn into the same disaster we see playing out everywhere (like schools).

Unfortunately, my superiors are busy lobbying for this or that little change and making quixotic attempts to bring a bad system under a bad state’s control. So I’ll sit here and keep stealing what little I can to help my patients until the dollar collapses and it all comes crashing down. I give it 10 months.

PS re Heilig’s use of “socialized medicine.” In 1998, when Rosie and I went to France to attend the International Cannabinoid Research Society meeting, we met Renault workers at the seashore enjoying four-week vacations. The missus commented, “A little bit of socialism goes a long way.”

PPS: Wikipedia informs us re Mission Bay: “Much of the land had long been a railyard of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, and was transferred to Catellus Development Corporation when it was spun off as part of the aborted merger of Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe Railway… It is also the headquarters, at 550 Terry Francois Blvd, of the Old Navy brand of The Gap clothing retailer.”

There is something symbolic about the Biotech-Medical Complex succeeding the Railroad at Mission Bay. It was the Railroad by which San Francisco’s first oligarchs made their unsavory millions and became the main target of Ambrose Bierce’s invective. Ditto the Fishers’ moving in right next door to UCSF’s splendid new campus.