At the recent Patients Out of Time conference in Tucson, Greg Gerdeman discussed a study he had conducted with anthropologists at the University of Arizona led by David Raichlin. O’S News Service summed it up this way: “Running and other forms of aerobic activity increase production of anandamide —the neurotransmitter that THC imitates— in the brains of certain mammals, including people. The authors… suggest that the brain’s reward system provided a neurobiological incentive for our remote ancestors to run for long distances. The incentive promoted survival and thus helped shape the evolution of the human body.”

On Tuesday, May 1, the New York Times weekly Science section ran an article by Gretchen Reynolds about the same study. The most remarkable thing about Reynolds’ very readable piece was how matter-of-factly she made reference to the endocannabinoid system.

Reynolds quotes Raichlin saying, “We wondered if natural selection might have used neurobiological mechanisms to encourage exercise activity,” then writes:

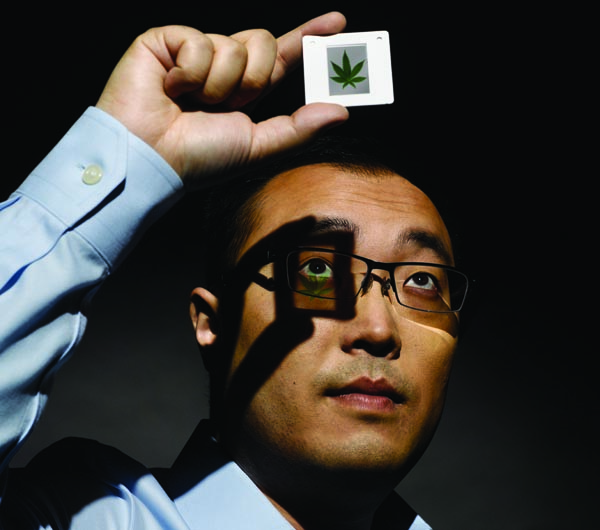

“… he and his colleagues became interested in the evolutionary role of the endocannabinoid system. As the name suggests, endocannabinoids are chemicals that, like cannabis in marijuana, alter and lighten moods. But the body produces endocannabinoids naturally. In other studies, endocannabinoid levels have been shown to increase after prolonged running and cycling, leading many scientists to conclude that endocannabinoids help to create runner’s high.

“But Dr. Raichlen wondered if the endocannabinoids had had a more momentous role in the development of mankind as a whole. Had we continued to run, as a species, not because we had to run, but because we had become hard-wired to like it?

“To test that idea, Dr. Raichlen and his colleagues decided to compare the endocannabinoid response to running in species that both do and do not historically run — to see, in other words, which animals experience a runner’s high…”

Breaking Through

It was seven years ago that Philip Denney, MD called excitedly to report seeing in his new issue of JAMA (The Journal of the American Medical Association) a full-page ad from Sanofi-Aventis touting “A NEWLY DISCOVERED PHYSIOLOGICAL SYSTEM… The Endocannabinoid System (ECS).” The ad was part of Sanofi’s billion-euro marketing campaign for Rimonabant, a drug that blocks the CB1 receptor.

The mention of the endocannabinoid system in JAMA seemed sufficiently newsworthy to warrant a piece in the Autumn 2005 O’S. Denney expected the Berlin Wall of Ignorance to fall in a heap, but it’s still standing. (I should have offered to bet him.)

Reynolds’ four paragraphs referencing endocannabinoids in the New York Times seems at least as significant as Nancy Pelosi’s headline-producing expression of misgivings about DEA raids on medical marijuana providers. Ending the fraudulent “War on Drugs” involves fighting on many fronts, and no battle is more important than getting the medical establishment to stop ignoring physiological reality.

Some illuminating comments by Gerdeman, an assistant professor of biology at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida, can be found on the Eckerd website.

Stylebook note: the abbreviation for “endocannabinoids” now generally used by scientists is “eCB.” But it looks odd and we don’t understand why the “e” should be lower case. “ECB” seems more logical.