By Fred Gardner in the Anderson Valley Advertiser, April 15, 1992

Somebody in the UC Santa Cruz administration was hip enough to invite Art Spiegelman to teach a history-of-comix class this spring. The timing couldn’t have been better: Spiegelman just won a Pulitzer Prize for “Maus,” a comic book about the effects of the holocaust on his family.

Rosie’s daughter enrolled in Spiegelman’s class –10 lectures over a four-week period, through May 5– and reported that it was great. So Rosie and Walter decided to visit her and to hear Spiegelman last Friday, when he was scheduled to give a 7 p.m. talk. They left the city at the end of the workday and drove down Highway 1 as the orange sun sank into the deep blue sea.

Walter had been fending off the flu that’s going around. In the car en route to Santa Cruz, for the first time ever, the smoke from Rosie’s Camel seemed too acrid and intense. He rolled down his window. Next time she lit one up he rolled it down again, all the way. He assumed she got the message. She thought he had the window down because it was such a beautiful evening.

Earlier in the week he had been handed legal papers warning that his boys would not be allowed to visit him if they were exposed to cigarette smoke (from Rosie). All across America such clauses are being inserted into similar documents; custody will be gained and lost behind secondary-smoke exposure. “It’s a reasonable request,” said peace-loving Rosie. “I don’t smoke in front of the boys.”

And just the week before that her son J. had urged her to quit smoking in his usual logical and loving way: “One of these days I’m going to have children and I’m going to need you to help take care of them.” J. had grown up with an old-fashioned grandma on the scene and he wanted his kids to have one, too. Walter hoped Rosie took the appeal seriously, because he, too, wanted her around for a long time. She reminded him a little of his mother, who smoked three packs of Pall Malls daily and could never quit, even though she was strong-willed and health conscious.

They pulled onto the Santa Cruz campus, got vague instructions from a jogger and parked. Then they followed a path beneath the eucalyptus up to a multi-level concrete plaza, hoping to find the lecture hall. The Santa Cruz campus always made Walter extremely uneasy. It seemed like a subtle concentration camp for youths who might otherwise cause trouble. The authorities figured that four years of political correctness with an ocean view would leave everyone confused, guilt-ridden and incapable of revolutionary action.

Walter and Rosie had expected throngs heading to hear Spiegelman, but there were only two other people in sight — a sweet-looking man in his late 40s wearing a black jeans jacket, and a young woman in a black motorcycle jacket– and they also seemed a little lost. “Are you coming to hear Art Spiegelman?” Walter asked. “I’m coming to be Art Spiegelman,” said the man.

As they strolled along Spiegelman said, “You might be seeing my last lecture.” A group called Students Against Smoking had complained that because he smoked while lecturing, he violated their right to hear him in a smoke-free environment. This right, Spiegelman pointed out, was merely theoretical, because he wouldn’t be there at if he couldn’t smoke. He’s shy about speaking in public and knew he’d need to have an occasional puff for reassurance, so he had cleared it with the UC Santa Cruz administratorswhen they offered him the job.

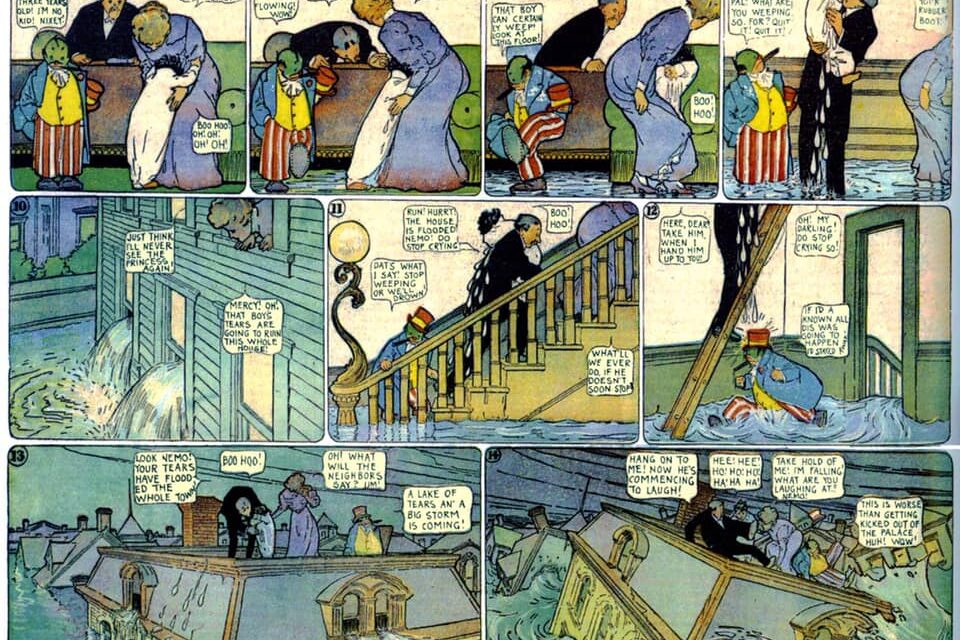

His talk that night was mainly about two artists who drew strips for U.S. metropolitan dailies in the first third of this century: Winsor McKay and Lionel Feininger. Spiegelman said that on the spectrum of respectability between the vulgar and the genteel, comix are obviously on the vulgar side and, as a result, the greatness of the artwork is ignored or marginalized. He showed slides of McKay’s work over the years. There was a black-and-white strip which was always about somebody who’d had a bad dream and awakened in the final panel saying “I shouldn’t have had that welsh rarebit last night.” The dreams were all psychologically interesting and drawn as if through fun-house mirrors.

“It’s his use of where to place the blacks on the page,” Spiegelman said in reference to one of the “Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend.” Immediately Rosie and Walter and probably everybody else in the lecture hall could see a pattern –the entire page underlying the 16 panels– they hadn’t noticed before. At one point Spiegelman used the term “very psychedelic” to describe one of these “Rarebit” strips. A student raised his hand to ask, “What exactly is Welsh Rarebit?”

“It’s a dish made with melted cheese,” Spiegelman explained.

Rosie, Walter and Rosie’s daughter all had the exact same thought as Spiegelman showed the Winsor McKay slides: “This is like ‘Mickey In the Night Kitchen.'” And sure enough, Spiegelman went on to say that “In the Night Kitchen” was Maurice Sendak’s tribute to McKay’s “Little Nemo” and Mickey Mouse.

There were many throwaway anecdotes like that spicing up the scholarly overview and insights. McKay’s originals were not fully colored in, Spiegelman said; they contained instructions for the engravers (his true collaborators) who were excited by the new color separation techniques and devoted themselves to achieving the most beautiful gradations. McKay’s son Robert, the original inspiration for Little Nemo, was evidently ambivalent about his father. At one point he ran an ad agency and was said to be using Winsor McKay originals as table covers, blotters and backing sheets. A dedicated fan named Woody Gelman offered to buy the original drawings but Robert refused. So one night Gelman broke into the office and stole them.

Spiegelman’s lecture was attended by some 50 students in a chilly theater. A door had been left open and the ventilation system was turned on to whisk away the traces of Spiegelman’s occasional puff. Unfortunately, equal attention had not been paid to the audio-video facilities; the fascinating slides couldn’t be brought into sharp focus and the sound was fuzzy. Attendance was down, according to Rosie’s daughter, because this session had been scheduled at such an unusual hour. (Presumably so that the public could attend. But the Santa Cruz campus is so remote that it’s hard to imagine the public auditing lectures there. Rosie and Walter went because they had a connection.)

Towards the end of the talk Rosie started sniffling and her throat felt sore. She was coming down with something and hoped it wasn’t what Walter was just getting over. Spiegelman ended by telling the class that the next session was iffy because the Students Against Smoking were protesting the deal he had made with the university. The students in attendance guffawed in outrage. A girl in the back row raised her hand and proclaimed, “There are students here with environmental illnesses. I myself have asthma. And I can attest that your smoking has not been a problem.” There was applause for the brave girl. Somebody suggested they all sign a petition asserting their right to hear Spiegelman. A goody-goody made a gratuitous little speech about not marching on the provost’s office: “That would be counter-productive,” she warned. (Nobody had suggested marching on the provost’s office.)

As things broke up Spiegelman was chatting with individual students and everyone was signing the petition. Rosie’s daughter asked one of her girlfriends to show off her new tattoo, a bird on her left arm. “Maybe someday she can have it removed,” Rosie thought but didn’t say.

They drifted out into the damp night air. Walter was cold and said so. Rosie fumbled for a Camel, lit it, took a deep drag and shivered. She coughed. He was worried about her. He said “I can’t wait to get into that nice warm little car” as they headed down the path under the tall Eucalyptus trees. As soon as they did get into it, she lit up another Camel. He snapped, “Put that fuckin’ thing out!”

She crushed it in the ashtray and said, “The honeymoon is over.”