In November 2000, Al Gore and George W. Bush were running for President, and so was Ralph Nader. On the Saturday before the election Ross Mirkarimi, Nader’s California campaign manager, asked me to bodyguard Laura Nader, Ralph’s sister, a distinguished UC Berkeley anthropologist, who was going to speak at an event that afternoon in Union Square. (At one point in my brilliant career I provided security at the Irish Cultural Center bingo game.)

“Why would she need protection?” I asked. Ross said that the Democrats had scheduled a rally to honor Gore as a champion of women’s rights, and a contingent of Greens was going to stage a counter-rally for Nader, featuring Laura. “Make sure she doesn’t get heckled or harassed,” was my assignment.

It was a chilly, gray afternoon and the two rallies were held without incident. Laura reminded her small crowd that the Clinton-Gore Administration had done “little to defend reproductive rights… It took seven and a half years to get RU486…Feminists should support progressive Democrats in Congress, rather than attacking Nader.”

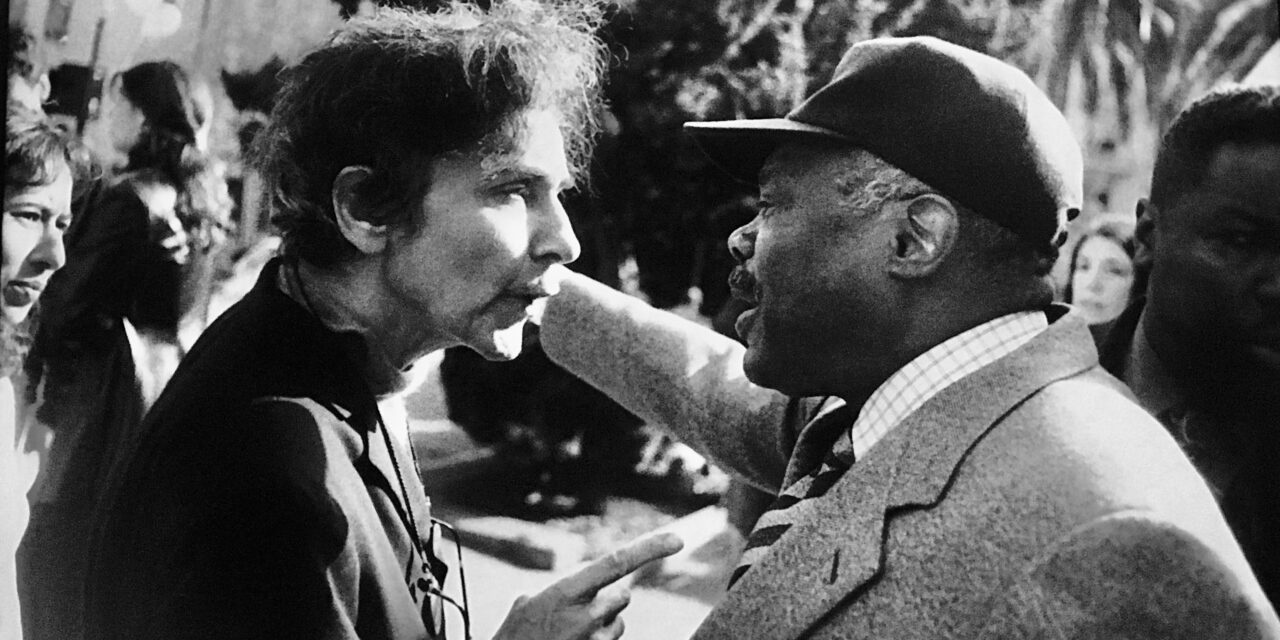

As the two rallies were winding down and I was starting to leave, Willie Brown confronted Laura Nader and began berating her to her face. In her face, actually, as the small, dapper mayor pressed to within a few inches of the graying, slightly taller professor. “If the Democrats lose it will be Ralph Nader’s fault,” was his theme, and he was furious.

I made a move to intervene but Ralph’s sister didn’t want any help. She let the tirade wind down, then said in reference to her brother, “If the Democrats were really democrats, they would have let him debate.” (The pundits had decreed that Al Gore lost the debate because he showed contempt for Bush’s stupidity by audibly sighing at one point. This supposedly proved that Gore was an elitist, whereas Bush was a regular guy. Nobody pointed out that if Nader had been allowed to debate, he would have been the intellectual on the left, Bush the doofus on the right, and Gore the solid occupant of the center. The Democrats probably would have prevailed.)

Why did Willie Brown, who had endorsed Terence Hallinan when he first ran for district attorney in 1995, want to see him done in by the start of his second term? I put the question to attorney David Millstein, the mutual friend who had asked Willie to endorse Terence back in ’95 and would serve for 13 months as Chief Assistant DA. Today Millstein and Willie Brown are both back in private practice, with offices in the same building (100 The Embarcadero). He said he would ask Brown.

Millstein wondered if I was exaggerating the rift. The two men went back a long ways. Brown had come from Texas, attended SF State and Hastings Law School, and was soon a fixture at the Hall of Justice, defending pimps and prostitutes. (In his very readable SF Chronicle column last Sunday, Brown referred to his days as a “street lawyer.”) In 1962, when Brown first ran for the Assembly, “Kayo” Hallinan led a squadron of DuBois club members to ring doorbells for him. In ’64 the DuBois club contingent was bigger and Brown won. In ’66, when the state bar association denied Terence a license because of his lengthy arrest record, Assemblyman Brown was among those who wrote letters attesting to his rectitude.

That was another century. In 2000 Brown was the mayor, Hallinan the DA, and social breakdown was becoming more visible by the week on the streets of San Francisco. Brown’s line to the media —identical to the Chronicle’s— was that Hallinan could solve the city’s problems by being less lenient. In July 2000 Mayor Brown strongly supported and Terence opposed an ordinance introduced by Supervisor Amos Brown, “establishing that any vehicle used to facilitate in the solicitation of acts of prostitution, or the acquisition or attempted acquisition of a controlled substance except marijuana is a nuisance and subject to seizure and forfeiture.” It was subsequently reworded to remove the marijuana exception.

At a hearing journalist Ellen Komp was among the pot partisans objecting to car forfeiture on civil liberties grounds. I summarized her observations in a note to Terence: “Big push by the police, many anti-Hallinan comments from residents of crime-ridden areas. Greg Suhr and Kevin Cashman leading the push. Sue Bearman [a progressive supervisor] said she hoped you’d be at the next meeting, which may be Monday 9/25. Ellen was struck by how much manpower the police devote to decoy operations, which means fewer cops walking the beat.”

A few days before the Supes voted on creating car-forfeiture, the Examiner reported that Capt. Kevin Cashman, head of SFPD’s vice squad, said such a law would be “an effective deterrent… Now pimps and prostitutes, johns and narcotics dealers and users commute to San Francisco to ply their trade rather than lose their vehicles in Oakland.” (Oakland’s vice squad had seized and auctioned off 288 vehicles thanks to that city’s car forfeiture law.)

Kayo summoned me to his office to draft a response. “Hookers will still operate out of San Francisco because the conventions are here,” he explained, not for the first time. “The hotels, the clubs, the concerts, the theaters, the Metreon, all the things that draw people to the city from all over the Bay Area… There could be unintended consequences. Johns might start parking their cars and proceeding on foot, which could lead to more stick-ups, people getting rolled…” He told me not to write that, he was just thinking out loud. I tried out a line: “Sometimes a reform that sounds good on paper will create unanticipated adverse side effects.” Kayo said, “Don’t even say it looks good on paper.”

He was confident that the supervisors would reject the bill —which they did. Even the Chronicle had come to see its serious flaws. The editors wrote, “Brown should be commended for pitching battle against street crimes that are partly responsible for the deteriorating quality of city life. Street-level drug dealing and prostitution not only destroy the character of neighborhoods, they often foster more insidious crimes such as rape and drive-by shootings in which innocent victims become inadvertent targets. But the proposed ordinance goes too far to combat these evils by jettisoning our judicial system and declaring a form of martial law… For those convicted, the punishment is disproportional to the crime. Surrendering a $25,000 car for an offense that carries a $100 fine is unfair. This ordinance punishes on suspicion alone, and it shifts the burden of proof so that citizens must show why their cars should not be held hostage…”

After the car-forfeiture ordinance was rejected by the supervisors, Willie Brown would never stop telling the media that Hallinan’s refusal to support it showed that he was unwilling to crack down on vice. “Brown excoriates Hallinan, other big-mouth critics,” read a Chronicle headline on Sept. 10, 2001. Matier & Ross reported:

“District Attorney Terence Hallinan is a ‘son of a bitch (who) should have been recalled,’ and the other ‘bigmouths’ who have been critical of the city’s homeless policy and dirty streets ought to shut up and do something other than make noise —so says Mayor Willie Brown in a biting interview with the San Francisco Neighborhood Newspaper Association.

“Here are some of Brown’s blasts:

“On Hallinan’s lack of prosecutions for people urinating, defecating and drinking on city streets: ‘That son of a bitch should have been recalled by the very people who are currently outraged. I’m more disgusted than you’ll ever believe.’

“Where were they when Amos Brown was carrying legislation to take the shopping carts, which was my legislation… Where were they when Amos Brown was carrying the legislation to get the panhandlers off the median strips?… And how much heat did I take when I cleaned out U.N. Plaza?”

Terence, for his part, never forgave Amos Brown for dissing him at the Supervisors meeting when he testified against Brown’s car-forfeiture ordinance. He was kept on the stand for 90 minutes while three supervisors grilled him about the prosecution of ‘quality-of-life’ crimes. After the 911 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, I mentioned that Amos Brown was taking heat for making a brave statement about the United States: “We’ve got to stop making people hate us.” Detecting my admiration Terence said, simply, “He’s a Hallinan hater.”

After the car-forfeiture ordinance was rejected by the supervisors, Willie Brown would never stop telling the media that Hallinan’s refusal to support it showed that he was unwilling to crack down on vice. “Brown excoriates Hallinan, other big-mouth critics,” read a Chronicle headline on Sept. 10, 2001. Matier & Ross reported:

“District Attorney Terence Hallinan is a ‘son of a bitch (who) should have been recalled,’ and the other ‘bigmouths’ who have been critical of the city’s homeless policy and dirty streets ought to shut up and do something other than make noise —so says Mayor Willie Brown in a biting interview with the San Francisco Neighborhood Newspaper Association.

Terence, for his part, never forgave Amos Brown for dissing him at the Supervisors meeting when he testified against Brown’s car-forfeiture ordinance. He was kept on the stand for 90 minutes while three supes grilled him about his prosecution of ‘quality-of-life’ crimes. After the 911 attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, I mentioned that Amos Brown was taking heat for making a brave statement about the United States: “We’ve got to stop making people hate us.” Detecting my admiration Terence said, simply, “He’s a Hallinan hater.”

Terence was always a bit mystified by Willie Brown’s animosity. Reading a headline in the Chronicle like “Brown excoriates Hallinan, other big-mouth critics,” he would shake his head in sad disbelief. When he said of the mayor, “He’s using me as a scapegoat, politically,” it was almost as if they might still be friends, personally. When Brown cut the District Attorney’s budget, Hallinan told reporters he thought there had been a misunderstanding that could be resolved if he and the mayor could “break bread” together.

“District Attorney Terence Hallinan is a ‘son of a bitch (who) should have been recalled,’ and the other ‘bigmouths’ who have been critical of the city’s homeless policy and dirty streets ought to shut up and do something other than make noise —so says Mayor Willie Brown in a biting interview with the San Francisco Neighborhood Newspaper Association.

“On Hallinan’s lack of prosecutions for people urinating, defecating and drinking on city streets: ‘That son of a bitch should have been recalled by the very people who are currently outraged. I’m more disgusted than you’ll ever believe.’

“On his critics: ‘I sometimes wonder where the hell they were when (former Supervisor) Amos Brown was taking all the heat for my proposal to snatch the cars of dope dealers who contribute to people (being) on the street…”

“The meeting of city department heads, that was quintessentially Willie. To assemble all these people —all of these critics of Terence— in a room. You mentioned the public defender, Jeff Brown. He hated us for no reason. He said he was progressive and we were progressives. Why would he hate us? He hated us because we were more progressive than him. He couldn’t solve any crime problems. And when Terence emphasized diversion, it affected his acquittal rate and made it look like he wasn’t getting people off anymore.

“Jeff Brown was anomalously against every program like drug court and prostitution court. He did an interview, I forget where, lambasting Terence and everything he did in his first year. There were plenty of supposed liberals who were doing that and they were all against him. It was sort of amazing that he got elected two times, I know how embattled Terence was, constantly. He was hated and reviled by the whole city bureaucracy, by basically everybody but the voters.”

Millstein asked, in conclusion, “Did Willie really say anything or do anything or direct anything besides call the meeting of department heads?”

Yes, I said, Willie did. He invited KRON’s Vic Lee to City Hall and let a cameraman get some long shots of the assembled bureaucrats seated around his magnificent conference table. And immediately after the meeting he gave Lee an exclusive interview in which he denounced the district attorney. He had run the recall-Hallinan idea up the flagpole, as they used to say, hoping that people would salute.