By Al Byrne My father was an infantryman during World War II —fought his way through North Africa and Sicily. My mother was a US Army dietician in North Africa who became pregnant with me and was sent home. My father wanted to stay in the Army after the war but he got out in 1946.

When I was 17 I got a scholarship to Notre Dame to play baseball. I joined Naval ROTC. Next thing I knew I was in a uniform and I was Marine.

I was sent down to Vieqes, Puerto Rico for training in the summer. I got off the boat on a landing craft. I remember hitting the beach. I woke up on a hospital ship, they said I was fine. Blown up by an artillery shell that had landed short. Seven men were killed.

I was commissioned out of Notre Dame as an ensign, transferred to a destroyer in Norfolk. We operated off the Atlantic coast and in the Caribbean. One day we were sent to Africa to rescue some Americans who had to be evacuated. I took in 60 men to get them out, and we succeeded.

After I got out of the Navy I was recalled and sent to Vietnam on my 25th birthday. It was 1970 and it felt like everybody was leaving, I was arriving. The first couple of weeks I was there I ran into what Vietnam was really like. I was moving with a marine patrol, we weren’t anywhere in particular, we weren’t doing anything in particular, there wasn’t anything to worry about. But in an instant we were under very, very heavy attack and it turned out to be an attack on our 50 men by about 3,000 Vietnamese. And I thought, “Well, this is where you die.”

That didn’t happen. We killed ’em all. Burned them. We got on a radio that cost a couple of hundred bucks and a jet came over that cost a couple of hundred million bucks and three thousand people died. And none of us died.

I spent a year there as an adviser. I traveled alone in Vietnam with different units doing different things. The carnage was awesome. It was all scary and pseudo-real like the Navy gunboats in “Apocalypse Now” that fight their way up the river mile after mile after mile and then all of a sudden there’s bright lights and a Playboy bunny.

I was sitting in a place one night in the middle of nowhere and a helicopter landed and out stepped Tex Ritter and John Ritter. They came to Vietnam to say “Hi.”

The people who fought in Vietnam, the kids who are fighting in Iraq today, the soldiers who fought in Korea, they have the worst day of their lives every day of their lives. It never stopped.There was no one day of trauma, there was a year of trauma. If you lived.

After a year they sent me home on my birthday I was now 26. The average soldier over there was 18 and a half and spent something like 350 days in combat. My father, who spent seven years in the Army, was in a combat zone for five years and spent two weeks in combat.

The intensity was enormous. The trauma was enormous. What makes it worse for combat vets in Viet Nam is that they were never treated at all. We came back and everybody said “You suck” and we went into the woods. Later on, the Agent Orange project was born. Vets got together and sued our own government because they didn’t take care of us. And we got a lot of money from the chemical companies that poisoned us.

I’m a victim of Agent Orange. I’ve had a rash on my bun for a long time. I sat in the wrong place.

In Virginia we formed an organization that went out into the Appalachian Hills and found vets who had gone into hiding when they got home and never came out. Most of the people I found up there were men and they were drunk. Alcohol was the only drug that they could blot out their memories with on a daily basis. These guys needed to sleep so they’d get drunk and pass out.

The daytime memories are bad enough, the nighttime memories keep you from sleeping at all. If you can’t sleep, your world goes to hell in a handbasket real fast and it doesn’t come back until you can get some rest. These guys needed to sleep so they’d get drunk and pass out.

There was as contingent of these guys that had been drunk but didn’t drink anymore -they smoked dope. I started going to VA Hospitals and guys would come up to me and say “Al, you see these pills the doctor just gave me -Valium, mood enhancers- you know what we do with these? We take em out on the street and swap em for cannabis.”

Because the VA won’t give them cannabis. So they take the prescription drugs that they will not use and sell them on the street to get cannabis, because it works. It calms down the emotional responses to problems that seem to flow through you for no reason sometimes.I can go back to Vietnam in a heartbeat if the smell is right. Just give me the right whiff and I’m there -and I’m terrified, because I was terrified in Vietnam, I was scared to death and anybody who tells you they weren’t wasn’t there.

And it lets me sleep. It lets me sleep because I do not dream. As a counselor working with other Vietnam vets in the Agent Orange program I would hear that over and over: “I don’t dream about anything. I smoke cannabis.” It’s very hard to talk about trauma -it’s embarrassing, it’s insulting, it’s terrifying, it’s confusing…

The other thing to realize about PTSD is: it’s not a disorder. When a new client came into our program in Virginia he’d get assigned to a vet as sort of a buddy to break the ice. It’s very hard to talk about trauma -it’s embarrassing, it’s insulting, it’s terrifying, it’s confusing, you need somebody to say “You’re not crazy, it’s just a reaction to what happened to you.” I would tell them “You’re not in a disorder situation, you’re in a situation that is organized around how to preserve your life.”

They have guns and knives all over their houses. I do. I have a gun in my truck. I have a concealed weapons permit. I’m scared of you. You tried to kill me…One of my clients was a nurse who worked in what you would think of as a MASH unit. Helicopters came in and took the broken bodies into the unit. I knew that she worked there from a counselor who had been in a helicopter before he got blown up and taken to that unit. But she didn’t remember it at all. She could not remember one moment in Vietnam. She has never worked a day in her life; she only works nights.

Post-traumatic stress is a mind-altering, life-altering situation that has to be dealt with to find a solution. Counseling helps if it comes quickly and it’s reinforced and it’s serious and compassionate and done by people who have had similar experiences and can really understand.

And cannabis helps. In my five years as a counselor up there in Appalachia I never saw another drug, prescription or otherwise, that had any effect on post-traumatic stress other than cannabis. Please spread the word.

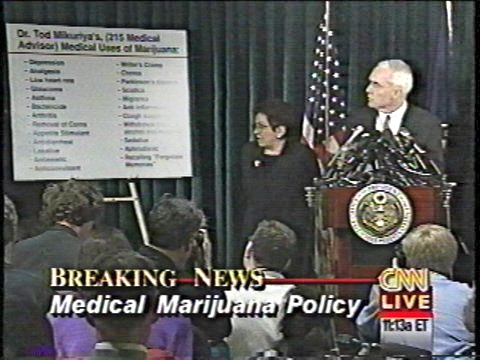

Published in O’Shaughnessy’s Spring 2006 from a talk given by Byrne at the Patients Out of Time conference in Santa Barbara.