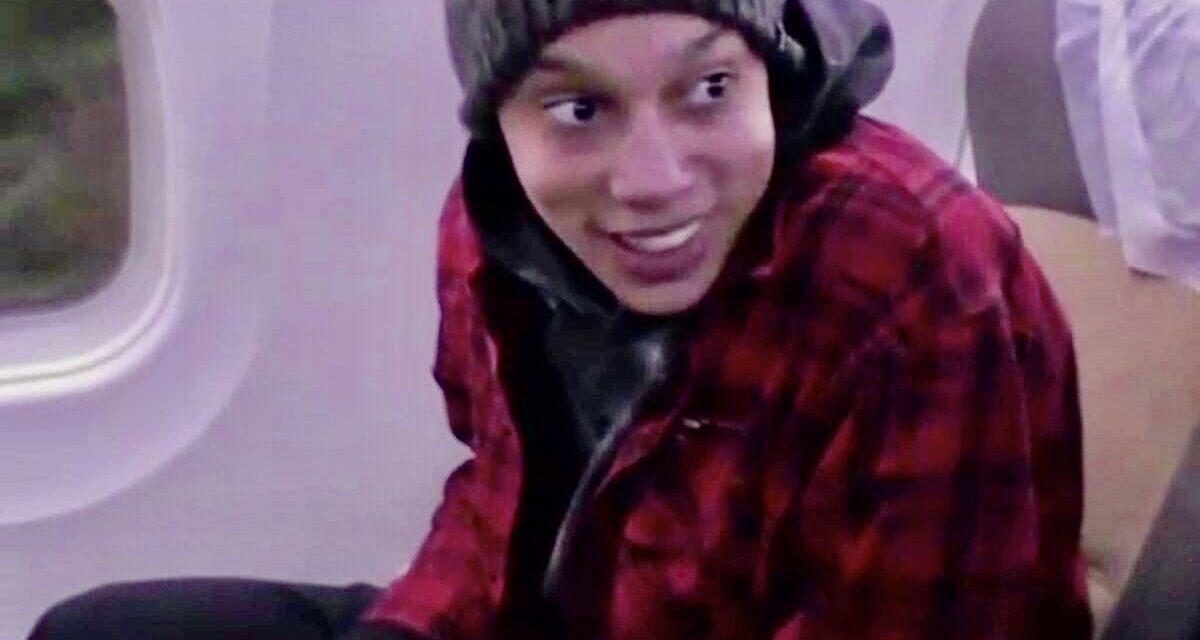

The joy on Brittney Griner’s face –pure relief expressed in a smile– came as a sweet surprise after all these months of seeing her grim and sad. The New York Times ran it on the front page with the story of her release Dec. 9.

Why does this woman need to spend a week getting debriefed (in the name of medical care) at a military base? Are the ganjapreneurs going to have a bidding war over which brand of CBD she’ll endorse? How come, with all the coverage of her arrest and detainment, the Times hasn’t run a single piece about Russia’s draconian marjuana prohibition? We’ve heard plenty about Paul Whelan, who’s doing time for espionage, but nothing about the Russian prisoners doing time for mere possession. (Russian prosecutors added a possession charge onto Griner’s smuggling charge.) But the Times continues to ignore Marc Fogel, a 61-year-old American teacher arrested after entering Russia in August 2021 with less than 20 grams (prescribed for him by a doctor in Pennsylvania for chronic pain). Fogel was sentenced to 14 years in a penal colony. Unlike Griner, he was not quickly classified as “wrongfully detained” by the US State Department.

Time.com (the website of the once-important magazine) reported on Fogel’s plight and noted that “From 2012 until his arrest, Fogel had been working at the Anglo-American School in Moscow, an elite private school that teaches the children of American diplomats and those of other international political figures.

Marijuana prohibition in Russia and the US had much in common until the two roads diverged somewhat in the 21st century. Both bans were rooted in racism and xenophobia. Marijuana came from Mexico and the Caribbean, then up the river from New Orleans, accompanied by jazz. Hashish came from Kazakhstan and lands to the East where it was grown and used by dark-skinned-people. In both countries, marijuana prohibition enhanced the power of the police over the people. In both countries, bans on marijuana (cannabis in drug form) co-existed with governmental promotion of hemp (cannabis grown for food or fiber). Patriarchs of the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches helped enforce prohibition. And in both countries the Cannabis “problem” was exacerbated by soldiers coming home from countries where hashish and marijuana were readily available.

It was in 1924 –two years after Lenin died and Stalin took over– that the importation of hashish was made illegal in the Russia, the largest republic in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. There had been a brief period of freedom after the revolution during which the artists cut loose. Had there been hash on the scene at Mayakovsky’s readings? Would Lenin have imposed prohibition? The fierce split with Stalin was over “the nationalities question.” Lenin had come to think that Ukraine and Georgia and all the republics should have real autonomy. Stalin, mad for private power, pushed for control from Moscow. If Lenin had lived and prevailed, would hash have remained legal in Russia? In Kazakhstan?

In 1928 Stalin, in total charge, banned sales of hashīsh, opium, morphine, heroin, and cocaine. According to Wikipedia, Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture and liquidation of the kulaks (small farmers) resulted in “shrinking of acreage, low yields, reduction in the commodity share of gross collections.” Hemp-for-fiber production rebounded in the 1930s as World War Two approached. A few years later, coinciding with Reefer Madness, the US Department of Agriculture urged farmers to grow “Hemp for Victory.”

More from Wikipedia: “Entering the 20th century, use of cannabis (largely as hashish) was confined to Russia’s colonial acquisitions in Central Asia. In 1909, I. S. Levitov produced a pamphlet based on his studies in that region, noting that locals had used cannabis for six centuries or more, and that Russian colonists and cossacks had acquired the habit from the locals.”

In 1934 the USSR “banned the unauthorized cultivation of cannabis and of opium poppy. A direct ban on the illegal sowing or cultivation of Indian hemp was introduced by Article 225 of the RSFSR Criminal Code of 1960, while hemp continued to occupy a significant place in the total volume of agricultural production… It was not until the 1960s that the issue received much attention from the Soviet government.

“In 2004 the drug policy of Russia was liberalized… The possession limit for cannabis was set at 20 grams, so that less than this amount would be only an administrative offense with no threat of jail time. Previously, possessing even a single joint qualified as a criminal offense.

“In 2006 Russia again changed the possession limits for various drugs, but this time to lessen the amounts. In regards to cannabis, the amount that triggered a criminal offense was changed from 20 grams to 6 grams. Less than 6 grams qualified as an administrative offense punishable by a 5000 ruble fine or 15 days of detention.

McPartland on Russian MJ Prohibition

Dr. John McPartland shared more of the relevant history with O’Shaughnessy’s: