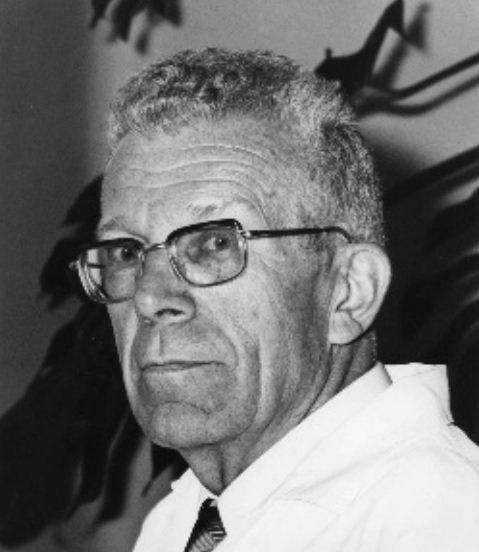

Dr. Hans Asperger was a striver who defined “autistic psychopathy” in terms the Nazis found useful, according to an April 1 op-ed in the NY Times by Edith Sheffer.

The official diagnosis of Asperger disorder has recently been dropped from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders because clinicians largely agreed it wasn’t a separate condition from autism. But Asperger syndrome is still included in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, which is used around the globe.

Moreover, the name remains in common usage. It is an archetype in popular culture, a term we apply to loved ones and identity many people with autism adopt for themselves. Most of us never think about the man behind the name. But we should.

Asperger was long seen as a resister of the Third Reich, yet his work was, in fact, inextricably linked with the rise of Nazism and its deadly programs.

He first encountered Nazi child psychiatry when he traveled from Vienna to Germany in 1934, at age 28. His senior colleagues there were developing diagnoses of social shortcomings for children who they said lacked connection to the community, uneager to join in collective Reich activities such as the Hitler Youth.

Asperger at first warned against classifying children, writing in 1937 that “it is impossible to establish a rigid set of criteria for a diagnosis.” But right after the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938 — and the purge of his Jewish and liberal associates from the University of Vienna — Asperger introduced his own diagnosis of social detachment: “autistic psychopathy.”

As Asperger sought promotion to associate professor, his writings about the diagnosis grew harsher. He stressed the “cruelty” and “sadistic traits” of the children he studied, itemizing their “autistic acts of malice.” He also called autistic psychopaths “intelligent automata.”

Some laud Asperger’s language about the “special abilities” of children on the “most favorable” end of his autistic “range,” speculating that he applied his diagnosis to protect them from Nazi eugenics — a kind of psychiatric Schindler’s list. But this was in keeping with the selective benevolence of Nazi psychiatry; Asperger also warned that “less favorable cases” would “roam the streets” as adults, “grotesque and dilapidated.”

Words such as these could be a death sentence in the Third Reich. And in fact, dozens of children whom Asperger evaluated were killed.

Child “euthanasia” was the Reich’s first program of mass extermination, begun by Hitler in July 1939 to get rid of children regarded as a drain on the state and a danger to its gene pool. Most of the victims were physically healthy, neither suffering nor terminally ill. They were simply deemed to have physical, mental or behavioral defects.

At least 5,000 children perished in around 37 “special wards.” Am Spiegelgrund, in Vienna, was one of the deadliest. Killings were done in the youths’ own beds, as nurses issued overdoses of sedatives until the children grew ill and died, usually of pneumonia.

Asperger worked closely with the top figures in Vienna’s euthanasia program, including Erwin Jekelius, the director of Am Spiegelgrund, who was engaged to Hitler’s sister. My archival research, along with that of other scholars of euthanasia like Herwig Czech, the author of a forthcoming paper on this subject in the journal Molecular Autism, show that Asperger recommended the transfer of children to Spiegelgrund. Dozens of them were killed there.

One of his patients, 5-year-old Elisabeth Schreiber, could speak only one word, “mama.” A nurse reported that she was “very affectionate” and, “if treated strictly, cries and hugs the nurse.” Elisabeth was killed, and her brain kept in a collection of over 400 children’s brains for research in Spiegelgrund’s cellar.

In the postwar period, Asperger distanced himself from his Nazi-era work on autistic psychopathy. He turned to religious themes and social commentary about child rearing. He would probably have been a footnote in the history of autism research had it not been for Lorna Wing, a British psychiatrist who tracked down Asperger’s 1944 article on autistic psychopathy.

She thought it lent important context to the narrower definition of autism then in use, and by the early ’80s, “Asperger syndrome,” and the idea of a broader autism “spectrum,” had entered the medical lexicon.

In 1994, Asperger disorder was added to the American manual of mental disorders, where it remained until it was reclassified in 2013 as autism spectrum disorder. Yet Asperger syndrome is still an official diagnosis in most countries. And it is ubiquitous in popular culture, where “Aspergery” is too often invoked to describe general social awkwardness, a stereotype for classmates and co-workers that overshadows their individuality.

Does the man behind the name matter? To medical ethics, it does. Naming a disorder after someone is meant to credit and commend, and Asperger merited neither. His definition of “autistic psychopaths” is antithetical to understandings of autism today, and he sent dozens of children to their deaths.

Other conditions named after Nazi-era doctors who were involved in programs of extermination (like Reiter syndrome) now go by alternative labels (reactive arthritis). And medicine in general is moving toward more descriptive labels. Besides, the American Psychiatric Association has ruled that Asperger isn’t even a useful descriptor.

We should stop saying “Asperger.” It’s one way to honor the children killed in his name as well as those still labeled with it.