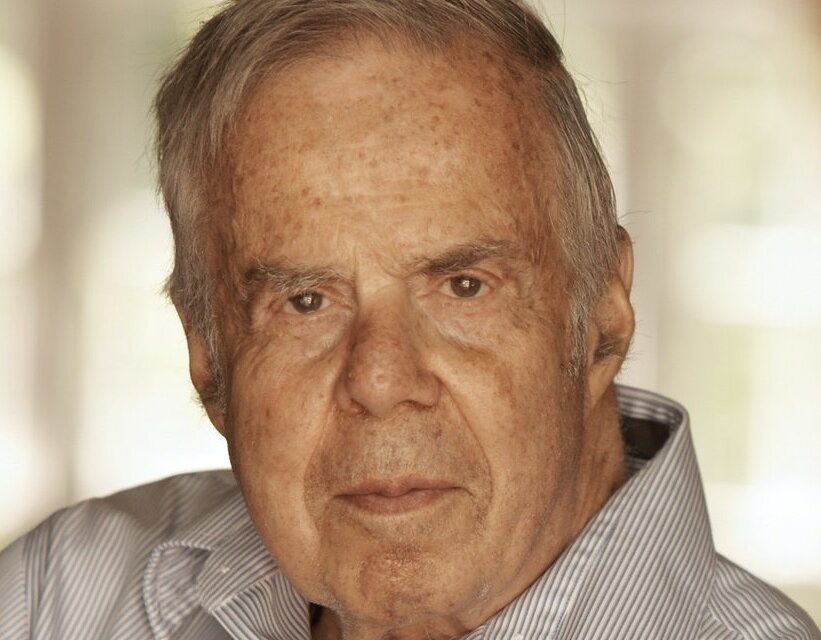

One of the most influential psychiatrists of our time, Robert Spitzer, MD, was profiled in the New Yorker Jan. 3 by Alix Spiegel. Spitzer was the driving force behind the 1980 and 1987 editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the “bible” of the American Psychiatric Association. The DSM provides a definition and a number for every ailment of the mind and spirit for which psychotherapists provide treatment, MDs prescribe medication, and insurance companies reimburse. By increasing the number of disorders and the broadness of the definitions, the DSM-III authors (establishment psychiatrists chosen by Spitzer) defined millions more Americans as sick, thus qualifying them for prescription drugs. This was the hidden, ultimate goal of the corporations that underwrote the “research” cited by the DSM authors.

Spiegel doesn’t convey the pompous fake rigor that permeates the DSM (she calls it “a scientific instrument”) but she does give a few tidbits about Spitzer’s own whacko personality. “His mother was a ‘professional patient’ who cried continuously, and his father was cold and remote,” Spiegel writes, having gotten it, obviously, from Spitzer (a severe case of Unresolved Parental Resentment Disorder). As a young man Spitzer paid for Reichian therapy in an “orgone accumulator.”

A former colleague says of Spitzer, “He would never say hello. You could stand right next to him and be talking to him and he wouldn’t even hear you. He didn’t seem to recognize that anyone was there.”

Another says, “He doesn’t understand people’s emotions. He knows he doesn’t. But that’s actually helpful in labeling symptoms. It provides less noise.”

According to Spiegel, “Spitzer is in his seventies but seems much younger; his graying hair is dyed a deep shade of brown.” (Symptom number one in Excessive Vanity Disorder.) “He admits that the patients he saw as a practicing psychoanalyst rarely seemed to improve… ‘I was always uncomfortable listening and empathizing, I just didn’t know what the hell to do.’” So this fiercely ambitious loser did “research.”

Robert Spitzer was the anti-hero of a great expose published in 1992 called “The Selling of DSM” by Stuart Kirk and Herb Kutchins. Spiegel of the NYer is not out to muckrake, but her description of the process by which DSM-III was compiled is devastating: “Because there are very few records of the process, it’s hard to pin down exactly how Spitzer and his staff determined which mental disorders to include in the new manual and which to reject. Spitzer seems to have made many of the final decisions with minimal consultation.”

The original DSM, published in 1952, defined 106 disorders. Spitzer’s DSM-IIIR listed 292, including attention-deficit disorder, autism, anorexia nervosa, bulimia, panic disorder and post-traumatic distress disorder, and others that are now household words and for which the pharmaceutical industry provides “medication.” Spitzer’s editions of the DSM simplified and made more inclusive the definition -or should we say the net- for many more conditions, including clinical depression, just as Eli Lilly was preparing Prozac for the market.

One day Spiegel of the NYer summoned the courage to ask Spitzer to explain the criteria for listing a new disorder in the DSM. “‘How logical it was,’ he said vaguely. ‘Whether it fit in… For most of the categories it was just the best thinking of people who seemed to have expertise in the area.’” If you define “expertise” as “the biggest drug-company grants” —which Spitzer literally did when he selected psychiatrists to write the DSM-III definitions— the intellectual corruption of the whole enterprise becomes clear.

“By far the most radical innovation” in Spitzer’s DSM, according to Spiegel, was the handy checklist of symptoms for each disorder enabling the harried practitioner to make a quick, easy diagnosis. She doesn’t point out that this, like all his other innovations, served to facilitate sales of corporate drugs.

The profile ends with Spiegel asking if Spitzer “ever feels a sense of ownership” when he comes across a reference in a newspaper to one of the disorders he defined. “He admitted that he does on occasion feel a small surge of pride. ‘My fingers were on the typewriter that typed those. They might have been changed somewhat, but they all went through my fingers,’ he said. ‘Every word.’” (Mad Cackle Syndrome.)