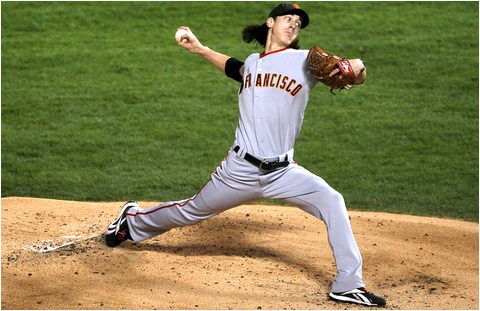

Oracle Park is where the Giants play in San Francisco. (It used to be PacBell Park. Can’t tell the corporate sponsors without a scorecard.)

Unite Here is a union representing some 270,000 US and Canadian workers in the hospitality industry. Its members are mostly women and people of color.

Bon Appetit is a for-profit company based in Minneapolis that provides “full food-service management to corporations, universities, and specialty venues.” The Giants contract with them to run the concession stands at Oracle Park.

On Saturday, Sept. 4 —on the eve of a big three-game series between the deadlocked Giants and LA Dodgers— the concession-stand workers belonging to Local 2 of Unite Here voted to authorize a strike at any time. The story was broken by 48 Hills, the Bay Guardian’s online ghost, and amplified in the SF Chronicle by a very good reporter named Alex Shultz. He explained that although Bon Appetit runs the Oracle Park concession stands, “the ownership group, in this case the Giants, dictates the relationship between Bon Appetit and concessions workers.”

The workers hadn’t had a raise in three years. They were contracting Covid-19 at a high rate and accused management of lax enforcement of the rules regarding masks and social distancing. Anand Singh, president of Local 2, put it this way: “It’s a negotiation between us and Bon Appetit… but the Giants hold the cards here. If the Giants were to decide today that workers should receive $3 an hour more, they could direct their subcontractors to make it so. That’s where the money is coming from, their own coffers. The Giants are in control of everything at that ballpark.”

Your correspondent sought a comment from Peter Smith, an olde acquaintance who used to sell beer, occasionally, at Giants games. Smith’s employer was a company called SwingShift that provided workers as needed at events. The Giants calculated that they’d save money by limiting the number of unionized workers on the payroll and hiring supplemental workers from the gig economy —like Peter Smith— for games that were sold out, even in the days when every game was sold out.

Smith points out that the two-tier employment system, like the Giants’ arrangement with Bon Appetit, undermines working-class solidarity. It’s obvious to all that there would be more union jobs if a reserve army of non-union workers wasn’t ready, willing and able to fill them. “I can get on well with anybody,” Smith says matter-of-factly, “but sometimes I could feel the union workers’ resentment. And one time there was an odd incident.

“You can’t serve more than two beers to one person. So this guy comes to my position. It looked like he was with some other guys. He ordered 10 or 12 beers, I can’t remember. And after he paid he handed me a $20 as a tip, which I put in my pocket. You’re not allowed to have a tip cup but we were allowed to accept tips. Obviously they have an eye in the sky because within five minutes the manager of the area showed up and wanted to know what happened.

“I explained, ‘This guy was with his buddies and I sold him 10 or 12 beers.’ He said ‘Did he gave you any money?’ I said, ‘Yeah he gave me a tip.’ He said ‘Let me have it.’ I was reluctant but he said ‘I’ll give it back to you after the shift.’ So I gave him the twenty.

“Did he give it back to you at the end?”

“No. They accused me of stealing six hundred dollars. It was ridiculous. They brought me down to the HR room and I said, ‘Search me. Where would I put six hundred dollars in cash? And I reminded them that most of the transactions were with charge cards.’

“They said, ‘We’ll have accounting look into it.’ I got the strong impression that they didn’t like having non-union help. The area manager with with Local 2 and the stand manager had been giving me dirty looks that day. Once she fired a kid from SwingShift in the middle of a game. So I asked the guy for my twenty back and he said, ‘Well, I have to keep it.'”

Before Covid-19 hit, Smith used to earn minimum wage on his SwingShift jobs. Since getting his second shot this summer and venturing back into the workforce, he reports, “Everything has totally changed. The event I worked on Friday a wedding in Novato, was $25 an hour. And a few weeks before that it was $19 an hour. If they don’t pay higher wages, they can’t get people to work.”

And that’s why pandemic unemployment benefits ended on Labor Day. Faced with the spectre of workers reluctant to report for duty and feeling pressure to raise wages, the boss class reveals its ruthless real self.

Do you think ending unemployment benefits on Labor Day was coldhearted? Labor Day was declared a federal holiday in 1894 by President Grover Cleveland exactly six days after the federal troops he’d ordered into action forced the American Railway Union to end their strike against the Pullman Sleeping Car company. The strikers, led by Eugene Debs, had seemed to be on the verge of victory before Cleveland called out the soldiers and authorized them to fire on the ARU members. Debs would go to prison on a conspiracy charge.

Despite the vote authorizing a strike on Labor Day 2021, the leaders of Unite Here Local 2 decided to keep negotiating with Bon Appetite. There’s a month left in the regular season, and the Giants look like they’re headed for the play-offs.

James Loewen

I didn’t realize that his greatness had been widely recognized until I read in his New York Times obit  August 20 that “Lies My Teacher Told Me,” had been reissued over the years and that Loewen’s publisher, The New Press, “called the book its all-time best seller, accounting for the bulk of almost two million Loewen books sold.”

August 20 that “Lies My Teacher Told Me,” had been reissued over the years and that Loewen’s publisher, The New Press, “called the book its all-time best seller, accounting for the bulk of almost two million Loewen books sold.”

Throughout the US these days there is a rightwing push to prevent the teaching of history that would supposedly diminish the self-esteem of white students. School board members who take the premise seriously should bear in mind Loewen’s analysis of how history textbooks ignore the rich/poor system:

“Teachers may avoid social class out of a laudable desire not to embarrass their charges. If so, their concern is misguided. When my students from non-affluent backgrounds learn about the class system, they find the experience liberating. Once they see the social processes that have helped keep their families poor, they can let go of their negative self-image about being poor. If to understand is to pardon, for working-class children to understand how stratification works is to pardon themselves and their families… Pedagogically, stratification provides a gripping learning experience. Students are fascinated to discover how the upper class wields disproportionate power relating to everything from energy bills to Congress to zoning decisions in small towns.”

About the sinking of the Titanic, Loewen writes, “Among women only four of 143 first class passengers were lost, while 15 of 93 second class passengers drowned, along with 81 of 179 third-class women and girls. The crew ordered third-class passengers to remain below deck, holding some of them at gunpoint. More recently, social class played a major role in determining who fought in the Vietnam War: sons of the affluent won educational and medical deferments through most of the conflict. Textbooks and teachers ignore all this.”

Also leaving us this sad summer: the beloved Berkeley professor, Leon Litwak, and the charismatic director of the Oakland Symphony, Michael Morgan.