For planting this item in the East Bay Express, the Claremont Hotel in Oakland deserves a Perfy (the PR industry’s coveted Perfumes-of-Arabia award for best cleansing of a corporate image):

“Some cities have wine trails. Others have beer trails, cider trails, even taco trails. Visit Oakland has just unveiled the city’s new Cannabis Trail — a network of eight cannabis shops that Oakland has been cultivating since 2006, when Harborside opened the first dispensary in town.”

Jeff Jones launched the Oakland Cannabis Buyers Club in ’97. Within a few years Paula Beale opened a club, and then Rich Lee opened The Bulldog…

“The tourism arm of Oakland calls this new attraction ‘a historical, colorful travel adventure’ and says research from 2020 shows that cannabis-motivated travelers in the United States account for 18% of all adult Americans.”

This cannot be true. An incompetence epidemic is raging in all fields. Be suspicious of all sentences containing the words “research shows.”

“The research also shows that cannabis enthusiasts want high-end experiences, which is why the Limewood Bar & Restaurant at the Claremont Club & Spa has been growing its Enlightened Dinner Series. The specialty dinners feature carefully curated cannabis pairings in the resort’s new outdoor venue, the Limewood Bungalow.

“Each dinner in the series is a pairing of locally crafted cannabis with four seasonally-inspired courses prepared by Chef Joseph Paire lll. Cannabis experts lead diners in an educational experience throughout the meal, discussing everything from the growing process and terroir to cultivation techniques. The cost of the dinner is $212 per person.”

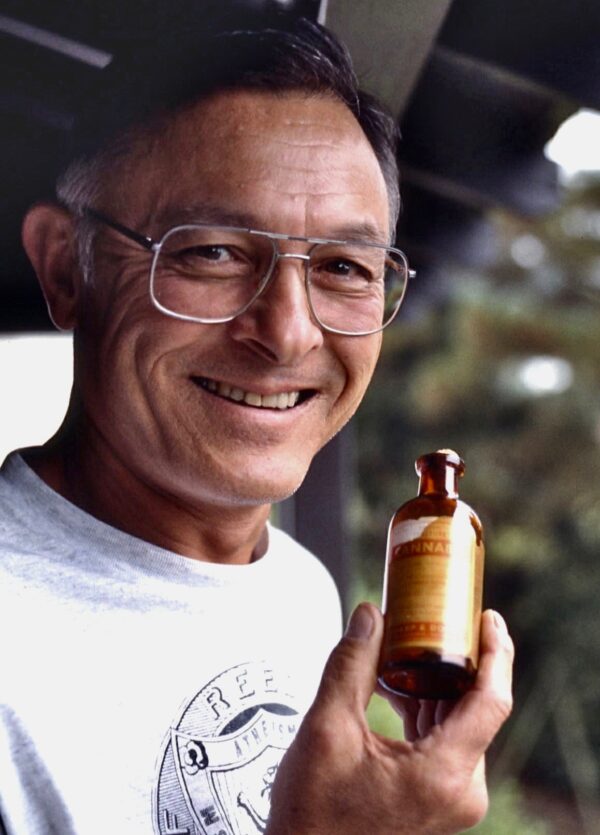

Herb Caen would have noted the pairing of Chef Joseph’s name and his special skill as a juxtaposer of foods. But that’s not the item… The Claremont, a magnificent old hotel in the Oakland Hills, really is a site that tourists interested in the history of marijuana legalization might want to visit. It’s where Dr. Tod Mikuriya was seeing patients in 1996, when California voters passed Prop 215, enabling people to use the herb with a doctor’s approval.

In his office hung a huge, gilt-framed line drawing of William Brooke O’Shaughnessy at a lab bench, holding up a beaker as if to offer a toast.

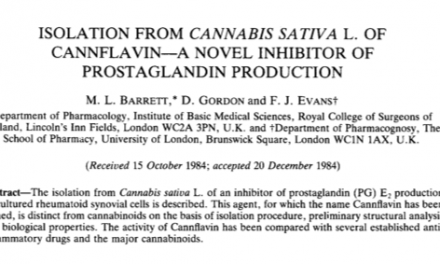

Tod told patients who inquired that O’Shaughnessy, “a personal hero,” was an Irish-born, Edinburgh-educated physician who in the 1830s had been sent by the British East India Company to Calcutta, where he observed and wrote about doctors using cannabis extracts to treat epilepsy and other conditions for which Western medicine had no effective medicaments. (O’Shaughnessy did not use the word “Cannabis” in his famous paper that introduced European doctors to the medical potential of the plant. He called it “hemp” and “gunjah.”)

Tod described getting the boot from the Claremont in an interview conducted one morning while he was driving to Sonora to testify for a patient charged with illegal cultivation. “I’d had my office there since 1981,” he recalled. “But soon after 215 passed, the Palo Alto Police Department requested of the management that they keep me under close observation. That outraged them but scared them at the same time. So, after 16 years, since there was a threat from the police and it was ‘Goodbye Doctor Mikuriya, you’re not part of our mix anymore,’ to quote the mealymouthed bureaucratic phrase they used. By the way, the manager was a man whom I’d given a credit reference to when he was new on the job, and played tennis with. So much for friendship.”

I emailed this quote to a longtime activist who responded, “The Palo Alto police? What jurisdiction did they claim over the Claremont?”

It’s easy to forget how thoroughly and zealously Law Enforcement pursued Tod after Prop 215 passed, and how alone he was. Except for AIDS and cancer specialists, very few California doctors, especially in the rural counties, were willing to approve cannabis use by their patients. Tod became known as the doctor of last resort. People who had been self-medicating with marijuana and now wanted to do so legally visited his office from all over the state, and he spent many week-ends flying off to underserved communities, where he would see 20± patients a day at ad-hoc clinics. During the first two years that marijuana was legal Mikuriya wrote some 4,000 letters approving cannabis use –approximately 1/3 of the total written by all the doctors in California.

Almost all the patients for whom he issued approvals had been using cannabis before consulting him. His approach to record-keeping was “minimalist,” he said, because he feared the feds might somehow gain access to his files. He was confident that the 15-20 minute exams he conducted were sufficient to take a full history, review a patient’s medical records and prior test results, make or confirm a diagnosis, discuss various aspects of cannabis use (he routinely advocated the use of a vaporizer), and note his findings and observations. His initial interviews, he said, “are always face-to-face, in person, confidential, and live.” He did follow-ups via video, phone, or e-mail if the patient so requested. “Successful doctor-patient relationships,” according to Mikuriya, “are characterized by candor and trust. Removing the stigma of criminality promotes candor and trust.”

In 1997 Senior Deputy Attorney General John Gordnier took the highly unusual step of sending an “Update” to all 58 California district attorneys asking them to notify him of any cases involving Mikuriya. Senior Investigator Tom Campbell contacted rural California prosecutors who had lost possession and cultivation cases to defendants whose marijuana use had been approved by Mikuriya, encouraging them to file complaints with the state medical board. In 2000, when the board formally accused Mikuriya of violating their vague “standard of care,” not one of the 46 complaints on file against him had come from a patient or a patient’s loved one. Nor were any of the complaints from other healthcare providers, Tod would note with a sad satisfaction. “They came from cops and sheriffs and deputy DAs in rural counties who couldn’t accept that a certain individual had the right to use marijuana for medical reasons. And not one of their complaints alleged harm to a patient.”

Mikuriya did not comply with the med board’s request that he turn over his patients’ records, but he provided them when in response to subpoenas. The files were reviewed by the board’s expert witness, Laura Duskin, MD, a psychiatrist employed by Kaiser, who had never approved cananbis use by a patient. After reading 16 of the cases, Duskin concluded that the pattern of inadequate care was so consistent and blatant that there was no need to cite all 46. An “amended accusation” was filed in June 2002 alleging that Mikuriya had provided substandard care to 16 patients.

Tod had hoped that Bill Lockyer, the Democrat who succeeded the arch-prohibitionist Republican Dan Lungren as attorney general in 1998, would call off the prosecution. (The attorney general conducts prosecutions on behalf of the med board. Doctors are tried by Deputy AGs before an administrative law judge.) Tod was deeply disappointed by Lockyer, felt betrayed. The two deputies Lockyer assigned to present the case against him, Larry Mercer and Jane Zack Simon, had been members of a task force created by Lungren to limit the implementation of Prop 215. The two of them, along with Gordnier, had prosecuted Dennis Peron in 1998 for running an alleged “nuisance” –the history-making San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club, the very place where Prop 215 was written!

According to Duskin, Mikuriya failed every patient –not by approving their use of cannabis, but by providing letters of approval stating that they were under his “supervision and care.” In the Court of Common Sense such phrasing –which implies an ongoing relationship instead of a one-time consultation– would be considered, at worst, a semantic error. Laura Duskin defined it as “an extreme departure from the standard of care.”

This is how the en-route-to-Sonora interview continued:

“But I’ll tell you, it’s one of the most satisfying experiences for me as a psychiatrist to be able to remove the stigma of criminality from an individual. Not just the self-perceived stigma, but removing real danger of civil forfeiture or other kinds of state viciousness. Giving them safe harbor from the cannabis prohibition cultists who have been running amuck.”

“So far the harassment I’ve received has been kind of soft-core –attacks on my credibility, forcing me to appear in court instead of accepting my written deposition… But I wouldn’t be surprised if Lungren went after me in his final days in office by notifying the Medical Board that I’m violating the ‘standard of practice’ by recommending cannabis to so many people… Ayatollah Lungren!”

Lungren ran for governor later that year and got only 39% of the vote against gray Gray Davis. It was his Democrat successor, Bill Lockyer, a so-called liberal, who prosecuted Dr. Mikuriya.

BTW, Tod had a saying: “It wasn’t just marijuana that got prohibited, it was the truth about history.”