“Stealing From the Rich: The Home-Stake Oil Swindle” by David C. McClintick (Evans, 1977) recounts how a Tulsa, Oklahoma lawyer named Robert Trippet masterminded the most lucrative Ponzi scheme of the 20th century. (Bernie Madoff began conning investors in the 1960s, but wasn’t exposed until 2008.)

Trippet graduated from the University of Oklahoma law school in 1941. “While in law school,” McClintick recounts, “he married Helen Grey Simpson, daughter of a wealthy Tulsa oilman. The wedding was lavish and gay. At the reception, Helen Grey slid down the stair banister of her parents’ home balanced on a mink coat.” Helen Grey came from a distinguished family. A great-great grandfather had been Attorney General when Oklahoma was still a territory. Her great-grandfather founded Home-Stake Oil & Gas Company in 1917. Her grandfather founded Home-Stake Royalty Corporation in 1929. Her father, Strother Simpson, had been a successful lawyer before taking over the family businesses in 1953. Helen Grey’s husband, Robert Trippet, would found a company called Home-Stake Production in 1955.

Strother Simpson, who had a sterling reputation in Tulsa, served as titular president at the start. All power resided with Trippet, the executive vice-president, who raised capital mainly by selling stock to people who had invested in the Simpsons’ Home-Stake companies. Trippet then bought properties on which to drill and began marketing Home-Stake Production as a tax shelter. (Investment in oil production can be deducted from taxable income. Thus a person making $200,000 in a year who invests $100,000 in oil production pays taxes on $100,000.) Trippet, according to McClintick, was “one of the first men in America fully to discern the appeal of oil tax shelters to wealthy people, and to devise a workable plan for marketing them on a large scale.”

From the start he siphoned off money for himself by various methods, such as setting up companies that supposedly provided services for Home-Stake and then pocketing the large sums paid to these companies. He had help in internal rip-offs from Charlie Plummer, a political fixer who Trippet employed as his top salesman. In February, 1957, certified public accountants auditing Home-Stake warned directors that Trippet had created five separate bank accounts into which he diverted company funds. Trippet gave the company a promissory note for $29,275 and closed the bank accounts. Home-Stake’s secretary-treasurer, “disappointed that the board didn’t take stronger action against Trippet,” resigned. Strother Simpson soon left the company.

Trippet made frequent trips from Tulsa to Manhattan, Los Angeles and Washington DC, to cultivate financiers, entertainers and lawyers –investors whose success, fame and influence would signal that Home-Stake Production was a very good buy. Sales soared after Trippet’s Washington-based lawyers got approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1964 for Home-Stake’s first public-offering prospectus. An SEC-approved prospectus, McClintick points out, can be “a more effective swindling device than a totally unregulated piece of sales literature.”

Unlike oil companies that drilled exploratory holes, Home-Stake –according to Trippet’s persuasive pitch– acquired oil fields that were no longer productive by conventional pumping methods, and then forced out the residual oil by injecting water or steam at high pressure. Whereas wildcat drilling was a gamble, Home-Stake was extracting oil known to be in the ground –”free storage,” Trippet joked to prospective investors. He was offering a tax-shelter that would also be a big money-maker.

Trippet successfully lured chairmen, presidents, CEOs and many high-ranking executives from General Electric, Pepsi-Cola, Citibank, Morgan Guaranty Trust, Walgreens, American Express, Procter & Gamble, Goodyear, Lazard Freres, Neiman-Marcus, Bergdorf Goodman, McKinnon, J. Walter Thompson, Armour, Eastman Dillon, Western Union, Bethlehem Steel, Macy’s, Heublein, Manufacturers Hanover Trust, Warner-Lambert, Warner Bros., Salomon Brothers, Gannett, Perkin-Elmer, National Cash Register, Singer, Merrill-Lynch, Dean Witter, International Telephone & Telegraph, and other major companies.

Investors from the entertainment world included Alan Alda, Ed Ames, David Begelmann (president of Columbia pictures) Jack Benny, Candace Bergen, Jacqueline Bisset, Bill Blass, Joseph Bologna, Renee Taylor, Barbara Streisand, Elliot Gould, Martin Bregman, Dianne Carroll, David Cassidy, Julia Cassini, Saul Chaplin, Tony Curtis, Bob Dylan, Phil D’Antoni (producer of The French Connection), Sandy Dennis, Phyllis Diller, Faye Dunaway, Mia Farrow, Freddie Fields, Bobbie Gentry, Leopold Godolsky, Buddy Hackett, Shirley Jones, Walter Matthau, Liza Minnelli, Thurman Munson, Ozzie Nelson, Mike Nichols, Tony Roberts, Buffy Sainte Marie, Barbara Walters, Andy Williams, and Jonathan Winters.

Some 36 partners in leading New York and Washington law firms bought into Home-Stake drilling programs. Their names meant nothing to your correspondent, except for Thomas E. Dewey, the former governor of NY who had been favored to defeat Harry Truman for the presidency in 1948.

McClintick includes examples of how the inside info was passed around. (Sharing investment tips seems to be a form of intimacy among the rich and famous.) “‘I first heard about Home-Stake when I walked into the locker room of my country club one Sunday morning to play golf,” recalls William H. Morton, who was soon to become president of American Express. ‘I ran into two friends of mine. One of them heads one of the biggest banks in the world. They said, “Bill, you should be in on this…”‘”

Comedian Phyllis Diller wasn’t joking when she recalled, “I knew that anything Andy Williams was into had to be pure gold.”

Why did Bob Dylan invest $38,000 in Trippet’s 1967 drilling program and another $120,000 in ’69? My Dylanest friend says, “What to buy would not have been Dylan’s call. He had a financial professional making those decisions –I think his name was Gilbert Haas. I’d heard he put Bob into Manhattan real estate.”

Every year Home-Stake’s promotional literature, in violation of SEC rules, understated the number of “drilling units” being sold, thus diluting the potential value of each unit. “The SEC has only enough manpower to enforce the law in relatively few cases,” wrote McClintick in 1977. Today Project 25 decimate the Securities and Exchange Commission and weaken the Internal Revenue Service, but as the Home-Stake swindle shows, these agencies weren’t very potent back in the day, especially when it came to making the very rich abide by the rules.

Trippet’s eldest daughter, Mary Susan –known as “Sudi” to family and friends, and as “Pebbles” later in life– grew up knowing that her father was preoccupied with his work. He used one room of their comfortable house as an office, and spent a lot of time in there at the typewriter. She did not know or even suspect that he was running a con. She sensed that her mother, once high-spirited, had become acquiescent in a loveless marriage. A skilled pianist, she no longer gave lessons or played much. She drank heavily.

“Your basic dysfunctional family,” says Pebbles. She began suffering painful migraines in childhood. Her identity as a political activist emerged when she was in high school, befriending a Black classmate and supporting the NAACP in integrating Tulsa lunchrooms. She was offended by country-club capitalism and every form of inequality, oppression and repression. She left Tulsa in 1960 for the University of Wisconsin, hoping to meet some fellow travelers. Her two younger sisters would have no buffer from the household tension.

Peak Profits

Home-Stake Production’s top salesmen were called vice-presidents. “For the most part,” McClintick observes, “they were lawyers, CPAs, or financial advisors whose clients depended on them to be objective in assessing investment possibilities, and free from conflicts of interest.” Harry Fitzgerald, who had been laid low by alcohol before Tripped helped steer him to AA, was in charge of the sales network. Fitzgerald was a charming son of the Tulsa elite who could have been a major league baseball player or a Joyce scholar. Trippet himself was the chief salesman, drafting all the brochures and pitches.

“Trippet wrote far more letters than the typical businessman,” according to McClintick. “He had an extraordinary ability to bolster, through letters, his image as an astute, conscientious, and capable oil man… Once he had an investor’s money, Trippet began sending quarterly progress reports saying the drilling was producing more oil than originally expected. The investor usually would begin getting small checks about nine months to a year after making his initial investment. Trippet made sure the checks always exceeded the extremely small amounts promised for the first two years.” (It takes a few years for oil wells to reach peak productivity.)

“Many investors were so impressed that they signed on for a second and a third year. They had no reason to be particularly suspicious until the fourth or fifth year, when payments were supposed to rise dramatically and didn’t.”

A New York businessman named William Rosenblatt began expressing doubts when his family’s payout for 1962 was $1,000, instead of the $3,550 projected when he invested in Home-Stake four years earlier. “Now Trippet had to deal with a dilemma that eventually confronts any Ponzi swindler,” writes McClintick. “He began by making plausible excuses about why drilling wasn’t going as well as expected. Most of the investors were so wealthy and had so many investments to keep track of, and Trippet had developed such rapport with them, that he managed to deflect many complaints for extended periods with nothing more than excuses… Complaints from Rosenblatt and others were only a minor annoyance for Trippet in December, 1962. He had collected another $4,195,368 from investors during the year.”

Rosenblatt persisted. In 1963 Trippet suggested that his family donate some of their Home-Stake holdings to charity. This, McClintick explains, “was an option devised specifically to placate disgruntled investors. Home-Stake prepared reports that set an artificially high value on the company’s billing shares. Then it proposed that the investor donate his shares to a university, hospital, or other charitable organization and take a second tax write off (the first having been taken for the initial investment). The evaluation report was given to the investor to show to the IRS if it raised questions about the value of the second deduction. It rarely did in the early years… Trippet frequently cited tax savings in trying to minimize the significance of investor losses.”

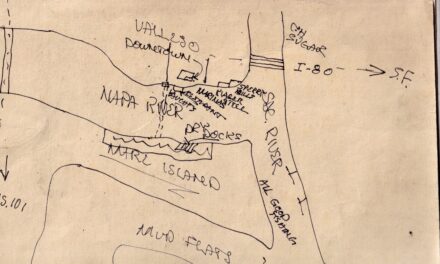

Before 1964 Home-Stake’s sales brochures had described the drilling programs and projected profits exceeding 400%. The company wasn’t allowed to make such claims in its prospectus, but salesmen continued to circulate them in a looseleaf binder known as the “Black Book.” Each investor got a Black Book with his name embossed in gold letters on the cover. The 1966 Black Book predicted great success for Home-Stake’s new drilling programs in Santa Maria, California: “Steamflooding is without doubt the most important development in the secondary recovery industry. Success ratios are good, and outstanding results are being achieved. From four specific projects we calculate that we will be able to recover 18,863,1o0 barrels of oil.” (How to Lie With Statistics.)

Although Home-Stake drilled approximately 110 holes in Santa Maria properties, fewer than half became functioning wells. Elaborate charades were staged for investors. “Visitors were driven to a particular well that appeared to be pumping oil from the ground,” McClintick recounts. “Expensively tailored men, sometimes accompanied by their mink-wrapped wives, would step from the station wagon, taking care to avoid getting too close to the greasy equipment or fieldworkers. On cue, a roustabout would turn a valve at the base of the well, and what appeared to be oil would gush forth into a jar. The valve would be closed. The jar would be taken over and shown to the investors. They would look at each other, smile, nod, and mumble how impressive it or was.

“What they weren’t told was that that particular well had malfunctioned and was rigged so that it would appear to be pumping oil from the ground when it really wasn’t. What they were seeing wasn’t oil; it was kerosene distillate, a substance that was circulated through some wells to keep them free of sand. Then the party would move onto another well – a functioning one that was equipped with a squirter –a nozzle-like device that, when turned on, would shoot a pressurized stream of oil against the face of a nearby bluff. Company staffers would take colored photographs of the investors standing next to the squirter as a chatty oil so they would have a tangible souvenir of their visit.

“The field workers hated the squirters because after the visitors left, the workers were required to clean up the oil that had been shot against the bluff. It was an extremely messy and time-consuming task. But Trippet insisted on the demonstration and gave detailed instructions on how the photographs of investors were to be taken. ‘You have to put the stream of water between you and the subject and also have to crouch down…”

Home-Stake raked in $9,499,430 in 1965 and $10,468,000 in 1966 from investors. The Rosenblatts had hired a Tulsa lawyer to negotiate a settlement, but Trippet was unyielding. They finally sued in September, 1966, claiming they’d been duped by false profit projections and that Trippet was stealing from the company. “The suit was on public file in the federal courthouse, but it attracted little attention,” notes McClintick. Trippet reckoned correctly that the Rosenblatts’ legal action –which had been joined by group of Memphis investors– would remain below the radar unless and until it came to trial.

When a famous celebrity or powerful businessman wanted out they would be accommodated. In 1967 Home-Stake agreed, McClintick writes, “to re-purchase interests for which Barbra Streisand had paid $238,545, leaving her only with a 1964 investment that cost her $28,200… The company could continue to claim her as an investor.”

Trippet made adept apologies. “Computer error” was a favorite. When the son of Henry Luce (founder of Time, Inc.) noticed that his pay-outs were declining, Trippet responded, “I am hastening to send you a correction check. I want to apologize for these errors on programming our computer. When the first error was made, it was programmed in permanently and has grown proportionately each time. There is no excuse for this. It reflects the kind of clerical help one is able to obtain these days.”

On December 29, 1967, Trippet agreed to buy back most of the Rosenblatts’ holdings, and they and their Memphis co-plaintiffs dropped their suit. Thus no allegations against him were heard in court. The Tulsa lawyer who filed the suit tried and failed to interest the regional office of the SEC in Home-Stake’s shenanigans. Charlie Plummer, the salesman who had sold the Memphis investors on Home-Stake, asphyxiated himself in his garage, holding a note that said “Tired of living.”

Trippet muted potential whistle-blowers within the ranks by paying well (“golden handcuffs,” one employee recalled) and buying off potential whistleblowers. When a retired Home-Stake petroleum engineer threatened to write an exposé, he accepted a $3,600 “consulting fee” and wrote nothing. “Stealing From the Rich” provides many examples of Trippet paying hush-money.

McClintick: “As Home-Stake’s drilling declined, its sales literature became more optimistic.” The 1967 annual report claimed that the company had developed “a stainless steel wire-wrap liner to keep sand out of the oil… that would enable the company to produce many millions of barrels of oil in a very economical way.” The report was not signed by an independent accounting firm. “Trippet took the calculated risk that few investors would bother to question the lack of independent accounting certification.” Annual sales kept rising. “Most of the corporate executives and lawyers in New York Washington and Los Angeles who invested in 1968 were back again in 1969 with even more money… A newcomer was Dr. Arthur Sackler (in for $200,000).”

In 1970 the SEC requested a meeting with Trippet in Washington. He sent Fitzgerald in his place, saying, “I’m not gonna let those Jew SOBs tell me how to run my company. They can go fuck themselves.”

When the SEC was slow to approve Home-Stake’s prospectus, Trippet did not feel threatened. He well understood, as McClintick explains, “Many investors’ attitude toward prospectuses in general was cynical. The SEC was forever making companies warn investors about the ‘high risk’ of this or the ‘speculative nature’ of that. Home-Stake retained a unique aura because of the prominence and sophistication of its clients.”

In 1970 Home-Stake took in more than $23 million. That November a New Yorker named Bernhardt Denmark complained to Tulsa lawyer R. Dobie Langenkamp that he was getting a lower return from Home-Stake than a friend who’d made an identical investment. Langenkamp confirmed the fact. (“Trippet had established a hierarchy of 16 pay categories,” McClintick explains, “ranging from ‘full pay’ for people he wanted to appease to zero for charities and others he didn’t fear.”) Langenkamp also realized that Home-Stake had not recovered much oil over the years, but had taken in $100 million from investors. When he drafted a lawsuit accusing the company of fraud, Trippet offered Denmark a refund. The suit was not filed.

Beginning of the End

Knowing that his scam couldn’t last, Trippet escalated his diversion of Home-Stake assets (mostly money from investors, not from oil sales) to entities he had created and controlled. The workforce in the fields was cut, and production kept declining. Home-Stake made a loan of approximately $3 million to Trippet via a crony.

The SEC finally sued Home-Stake in February, 1971 for circulating their Black Book without registering it, and knowing that the estimates of oil to be recovered were vastly exaggerated. Trippet, according to McClintick, “was relieved that the agency had focused only on the 1970 program and had failed to penetrate the overall fraud. But outwardly Trippet displayed a great deal of righteous indignation.”

In a memo to Home-Stake officers and key staffers, Trippet wrote, “The lawsuit is without merit and we will defend it vigorously.” In April ’71 Home-Stake settled the SEC suit by agreeing to offer a refund to investors in the 1970 drilling program and putting $23 million in escrow. Investors were advised that “Some of the information dispensed in 1970 was misleading or without foundation,” and given five months to request payback. McClintick waxes psychological: “Trippet bet that when wealthy investors were told about disappointing profits, they would rationalize that they had still been prudent investors because they had sheltered their money from taxes… By donating their stock to charity, the swindled investor could maintain a positive self image… In the end only a little more than $5 million was reclaimed, leaving Home-Stake with more than $18 million.

“It seems remarkable that Home-Stake raised any new money at all in 1971,” writes McClintick, but they took in nearly $14 million. George J.W. Goodman, an acclaimed financial expert who wrote two best sellers under the name “Adam Smith,” invested $120,000. But ’71 was the first year that the company didn’t meet its sales goal. Questions about its legitimacy were spreading. In April Home-Stake’s treasurer, Elmer Kunkel, resigned.

Harry Fitzgerald, the ace salesman, resigned in July. Trippet offered him a raise. He turned it down. Trippet offered to put $500,000 in Fitzgerald’s wife’s bank account “and nobody would ever know where it came from.” Fitzgerald nixed the bribe. Soon Fitzgerald and his wife were harassed by anonymous phone calls. Threats were made against their children. Fitzgerald left town. In Los Angeles he got an anonymous letter claiming that photos of him having sex with another woman would be sent to his wife if he didn’t pay $30,000. The DA’s office taped a follow-up phone call –Fitzgerald stalled, said he was trying to raise the money– but the harasser was not heard from after that. The reader infers that Trippet used mobster tactics in a vain attempt to pressure Fitzgerald to rejoin the company.

In Washington, attorney Harry Heller (formerly an assistant director of the SEC’s corporate finance division), who had been steering Home-Stake’s prospectus through the approval process since ’64, was hearing rumors that the company was spending much less on drilling than it had raised from investors for that purpose. He confirmed the truth from Conrad Greer, the engineer in charge of the Santa Maria properties. Greer resigned in September, but Trippet convinced him to stay on for a month. On October 8 Greer accompanied Trippet to a meeting in New York with an IRS agent who was auditing the tax returns of Faye Dunaway. The agent was an engineer who specialized in evaluating oil companies. His concerns were not allayed. He recommended that the actress’s $47,298 gift deduction be cut to $7,898.

Also in October ’71 the Chase Manhattan Bank, acting as executor on behalf of two deceased investors, hired Dobie Langenkamp to sue Home-Stake in federal court in Tulsa. “It was the first suit formally to allege that Home-Stake was a Ponzi scheme,” writes McClintick. “A headline in the Tulsa World read: ‘NY Bank Alleges Fraud in ‘Pyramid’ Suit Here.’ But the lawsuit received no publicity elsewhere, and there weren’t any Home-Stake investors in Tulsa. The suit was settled quietly a month later, when Home-Stake agreed to pay $303,690.”

In December Harry Heller dropped Trippet as a client. Heller had been outraged to learn of a $3.2 million deposit Trippet made in 1969 with a bank in the Bahamas. Trippet promised to return the funds, but was scheming to keep $2,650,000. (This maneuver was too complex for your correspondent to understand, let alone summarize. Trippet had described it jokingly to Fitzgerald as “the great train robbery.”)

In 1972 Home-Stake investors accelerated their gifts to charities. Corporate chieftains often made donations to their alma maters. Thomas Gates, a former Secretary of Defense, gave more than half his Home-Stake stake to the University of Pennsyvania. Candice Bergen favored the Library of Congress; Tony Curtis, the American Cancer Society; Jack Benny, the Jewish Federation Council of Greater Los Angeles.

Despite its fraying reputation, Home-Stake took in $5.4 million in ’72. Investors were lured with a plan to drill gas wells in Ohio. One gullible investor explained, “I fell for the excuses… We received a lot of clippings from the Wall St. Journal that gas is the thing of the future.” When he didn’t “hit a bonanza,” he was mollified by the tax deductions.

Con vs. Con

If the chapters of McClintick’s book had titles instead of numbers, 11 could have been called “Con vs. Con.” With his Ponzi scheme nearing its inevitable collapse, Trippet put out word that his health was failing and he was seeking new management for Home-Stake. A mutual acquaintance told Mike Riebold, a Mexico businessman with an urgent need for cash, that Home-Stake had $5.4 million in assets from its 1972 drilling program. Also, that Trippet “had had his problems in the past years, mainly with the SEC and the IRS, and he was tired of fighting the battle and he was looking to find management that he would turn the company over to, who could carry forward with Home-Stake Production and wouldn’t go out of its way, go back into past history and dig up things.”

As of May, 1973, Riebold had squandered the money his three small oil, gas, and mining companies had taken in from investors, and most of the $6 million he had borrowed in a series of loans from the First National Bank in Albuquerque. To get these mostly-unsecured loans, Riebold had bribed a senior vice-president at the bank, Don Morgan, with $27,000 in cash and a big chunk of stock in his American Fuels company. Both men knew that the illegal loans would be exposed at the next audit by federal bank examiners.

A Home-Stake executive with friends in Albuquerque warned Trippet that Riebold was considered “a rascal, unscrupulous, cheat, liar and confidence man. He had fleeced everybody that had had any association with him.” Trippet was not put off. “He held at least a dozen meetings with Riebold and his henchmen over the next several weeks,” McClintick recounts. Plans were made for one of Riebold’s men, Carlos Robinson, to become CEO of Home-Stake as of June 18. Trippet notified stockholders by letter that Robinson had “extensive experience in all management phases of the oil and gas industry as an independent operator.” Also, that company headquarters might be moved to Denver or Houston.

Riebold’s takeover of Home-Stake was completed July 10 when three more of his men were appointed directors and two long-time directors resigned. Carlos Robinson became CEO and Trippet –by pre-arrangement with Riebold– was fired. This, McClintick explains, “would make it easier for him to blame the new management for any problems discovered at the company.”

Trippet’s input was still needed, however, and he didn’t vacate his office. He made a list of assets that Riebold could sell quickly for cash. He provided on-the-job training for the new directors. (One was an insurance agent, one a physician, and one the manufacturer of a cleaning compound.) Trippet notified his long-time banker at First National of Tulsa that he was leaving Home-Stake for health reasons, and introduced him to Riebold and Robinson. They immediately transferred $3,750,000 to Albuquerque, thus allaying suspicions of the bank examiner who had questioned Morgan about his loans to Riebold.

Dobie Langenkamp was preparing a suit for a group of disgruntled New York investors who had put more than $4 million into Home-Stake over the years. “On July 18 he drove to Oklahoma City and got a temporary restraining order barring the removal of Home-Stake funds or records from Tulsa.” He was too late to block the transaction. Also on July 18 the under-staffed Washington DC office of the SEC authorized the over-extended Fort Worth office (which has jurisdiction over Tulsa) to swoop down on Home-Stake. Two investigators arrived on the tenth floor of the Philtower Building to serve subpoenas on company officers and warn them not to conceal or remove evidence. McClintick describes Trippet as “smooth and cordial as he accepted his subpoena with a smile.”

Langenkamp’s next move was to have a court order served on Carlos Robinson with a demand that the money be returned from Albuquerque to Tulsa. Robinson told Riebold he was scared, wanted them to comply. Realizing he had no choice, Riebold got unsecured loans for $2,880,000 from First National Bank, where Don Morgan was no longer being scrutinized by a bank examiner. Trippet would be relegated to a small office on a lower floor and Robinson had the locks changed on the main office suite.

Another legal front was opened on July 30 by William Wineburg, a San Francisco lawyer representing disgruntled investors who arrived at Home-Stake’s office with two assistants, two clerical workers, a portable microfilm machine and court permission to inspect the company’s books. SEC investigators joined Wineburg in examining Home-Stake’s records. Eventually they came across a print-out of investors’ names, each with a mysterious number alongside it. It turned out to be proof of unequal pay to investors –the essence of a Ponzi scheme. Wineburg filed his suit September 6. The SEC filed suit the next day.

The IRS was on the case, too, McClintick writes, “after years of sporadic auditing of a few Home-Stake investors by local offices,” McClintick notes. “For the most part, the IRS compromised on those audits, leaving intact major portions of the investors’ deductions. By the late summer of 1973, however, the IRS was challenging hundreds of drilling and gift write-offs.” Home-Stake was found to owe almost $1o million in back taxes for 1969 alone! The directors installed by Riebold got legal help and sued Trippet and his top executives for fraud, theft, and mismanagement. Because Home-Stake was insured against employee dishonesty, they also filed a claim with Aetna, alleging that Trippet had stolen more than $4 million from the company.”

On September 20 Home-Stake was declared officially insolvent. A retired judge was appointed trustee. “The investors were protected from further fraud,” McClintick writes, “but nobody cheered.” Home-Stake had taken in slightly more than $140 million over 18 years. It had paid out at most $50 million, and its common stock tanked from $12 million to zero. Because the investors’ tax deductions were mostly fraudulent, the ultimate victim would be the US Treasury –meaning US taxpayers.”

Soft Landing

McClintick foreshadows the ultimate outcome: “If a swindle is as complex as Trippet’s and the swindler is as smart and as well-financed as he, proving him guilty of a crime or liable for damages usually is far from simple, no matter how blatant the fraud may appear to be. White-collar criminals frequently emerge from litigation and the criminal-justice process with light punishment and much of their fortunes in tact.”

The SEC prepared a criminal indictment for the Justice Department to prosecute. The Manhattan US Attorney’s office wanted the case, but the DOJ assigned it to Los Angeles, where the head of the fraud and special prosecutions units, Stephen Wilson, had “an impressive string of convictions to his credit.”

Wilson spent months interviewing witnesses and prepared an indictment that dated the conspiracy from the launch of Home-Stake in April, 1955. Trippet was accused of 22 counts of securities fraud and making false statements in SEC prospectuses; 12 counts of filing false income-tax returns; and three counts of using the US mail to defraud.

“At the trial, all of the evidence will come out,” Trippet wrote in a statement to the media, “and I sincerely believe that… my innocence will be established.” He and his co-defendants then sought a change of venue, citing what McClintick terms “an obscure provision of federal law that permits people accused of certain tax crimes to be tried in the jurisdiction where they live.”

The DOJ maneuvered to keep the case in L.A., but a federal judge –after eight months of pondering– decided it should be held in Tulsa. “Stephen Wilson’s duties as head of the Los Angeles fraud and special prosecutions unit prevented him from handling a major trial outside Los Angeles,” McClintick explains. The case was handed off to William Hawes, 31, a relatively inexperienced lawyer who simplified his task by re-writing the indictment. Instead of alleging that the conspiracy began in 1955, the new indictment said it started in 1967. Important aspects of the scam were ignored. Allegations against four defendants were dismissed.

In Tulsa the suit would be tried by Allen Barrow, the chief federal judge, who had known Trippet since their days at law school. Trippet added a fourth lawyer to his team –Patrick Malloy, who McClintick describes as “known to be particularly adept at plea-bargaining and for being a close friend of Judge Barrow.” Malloy then negotiated a deal whereby Trippet would plead “no contest” and get off light. The other defendants made similar arrangements, except for Norman Cross, who had been Home-Stake’s CPA. McClintick covered his trial for the Wall St. Journal. He was appalled by Judge Barrow’s obvious bias and the prosecution’s incompetence.

The judge, according to McClintick, “lost few opportunities to display… his disdain for the rich, out-of-state city slickers who claimed to have been cheated by Bob Trippet… His prejudices and his limitations as a judge were on display throughout. ‘When the so-called Okies left Oklahoma, it improved the IQ of Oklahoma and California also,’ he told a Los Angeles witness who had invested heavily in Home-Stake. Of entertainment celebrities Barrow said, ‘I wouldn’t go across the street to get a photograph of one upside down standing on their head.’ He showed a remarkable propensity for misstating certain facts of the Home-Stake case and portraying the wealthy investors as stupid, greedy and undeserving of sympathy.”

In a farcical flourish, Barrow ordered Trippet, along with Harry Fitzgerald and a Home-Stake VP named Simms, to spend 24 hours in jail before he sentenced them. Then –playing to a crowd that knew the fix was in– the judge pretended to scold Trippet, who pretended to have learned his lesson.

Barrow: Mr. Trippet, you have spent a night in jail, a day. I don’t think you liked what you saw, did you?

Trippet: No, your honor. I think that the experience I have had would have a big impact on anybody. The room was fully spotlighted all night long, very noisy, and I slept not a wink, and I remember it vividly.”

Barrow: I imagine you will remember it forever.

Trippet: I am sure I will.

Barrow: But you can imagine what 50 years would be like then.

Trippet: Yes, sir.

Excused, Trippet “settled into a chair at the defense table, leaned back, and surveyed the scene like the chairman of the board he once was.”

(McClintick, a reporter, occasionally writes like a novelist.)

“Barrow then called on his long-time friend and confidant, Pat Malloy, the lawyer who had negotiated the no-contest plea for Trippet. Malloy –a bluff Irishman with long silver hair, a flushed face, and a small potbelly– orated for 15 minutes. He pleaded for mercy for his client. He said Trippet entered his plea not because he was guilty but because of the ‘persistent and recurrent tragic serious health problems plaguing not only the defendant, but also members of his family.’

In addition, the Home-Stake criminal case had been based mainly on “falsehoods originally initiated by the press. A lack of serious investigation and a flair for sensationalism and the dramatic all led to the appearance in the Wall St. Journal of a feature article that catapulted the California prosecutors into the hurried and irresponsible indictments – ‘Ponzi scheme,’ ‘pink pipes,’ ‘black books’ ‘missing money stashed in Swiss bank accounts,’ catchphrases, movie stuff, Arthur Haley novel material. But not evidence. Fortunately, your honor, still in this country newspapers do not convict when the judges involved are guided by the evidence, not headlines, and by fact, not pressure…'”

McClintick responds in a footnote: “It would seem wise to say for the record that the press initiated nothing in the Home-Stake case… As Malloy and Judge Barrow knew or should have known, the original Wall St,Journal article and other stories reported the existence of some 30 lawsuits and voluminous other documents filed months earlier by the SEC and well over 100 investors. The lawsuits asserted unanimously that Home-Stake had operated a giant Ponzi scheme and offered substantial evidence to support their allegations.”

By the time Robert Trippet began fending off suits from those he had bilked, most of his Home-Stake millions had been put into Helen Grey’s accounts. His “no contest” plea –never having admitted guilt– would help him greatly in civil litigation.

In 1982 “Stealing from the Rich” was re-issued with an epilog from McClintick:

“By the autumn of 1982, five years after the publication of this book, the Home-Stake litigation had grown into one of the most complex protracted securities and tax fraud cases in history. Depositions have been taken from more than 100 witnesses and generated more than 100,000 pages of transcript. Tens of thousands of documents had been analyzed. But only mixed results had flowed from the investors’ attempts to recover funds from convicted conspirator Robert Trippet, the Home-Stake corporation and the other alleged swindlers. The IRS’s efforts to collect back taxes both from Home-Stake and the investors had fared no better.

“After initially pressing a tax claim of $31.3 million against the Home-Stake Production Company, the IRS settled for only $3.2 million, or about 10 cents on the dollar –a settlement typical of IRS capitulation to corporate taxpayers.”

The last of the civil suits wasn’t settled until 1996. Robert Trippet died in 2000, Helen Grey in 2004.

The Rebel Girl

Pebbles Trippet learned something useful from her old man, even though she had no interest in his business affairs. He took her to Tulsa Oiler games and taught her the basics of baseball and how to keep score. He taught her how to drive stick shift on a classic 1950 Mercury (the family’s second car, the first always being a Cadillac). And it must have been from him that she inherited her extraordinary drive (as in “determination to go all the way.”)

Pebbles had suffered intractable migraine headaches since early childhood. When she began smoking marijuana in the 1960s, she realized it had a palliative effect. It wasn’t until she moved to San Francisco in 1972 that legalizing the herb became her primary focus as an activist.

In 2017 NBC San Francisco aired a documentary that gave Pebbles proper credit for advancing the movement. Peter Coyote narrated the 45-minute video, which used the Ken Burns template of integrated interviews, still photos and spoken commentary.

Coyote: With the war winding down, Trippet turned her organizing skills to the growing marijuana movement. In 1972 she helped get the California Marijuana Initiative on the Ballot. Proposition 19 would be the first time Americans could vote on marijuana. It was doomed to fail, but…”

Trippet: It was a surprisingly good showing. We won 33% of the vote. Out of the blue. No one had ever thought of it before… The public had no idea what it thought. We felt that was a tremendous victory… ‘Let’s go on in 1974 and let’s do it again!”

Coyote: Trippet had been using cannabis to control her migraines for years. She carried low-potency joints in her car. (Close-up of rolled joints)... Every time she was arrested, she argued that it was her medicine. And she was arrested a lot.”

Trippet: I was busted 10 times in 10 years in five counties. It was usually on the road driving late at night. My Sonoma County bust came in 1990. My Marin County bust in 1992. My Contra Costa bust in 1994, and also the Humboldt County bust and the Palo Alto bust.”

Coyote: Trippet had a plan: aim for the Supreme Court. She went to the law library at UC Berkeley and read up on every case involving marijuana. Trippet learned how to file court papers and how to defend herself… She found hope in the US Constitution.”

Trippet summarizes the ways in which she saw marijuana prohibition as unconstitutional: “It’s cruel punishment to punish a medical act… It wasn’t statutory law, it wasn’t California law, but I had ‘Unreasonable searches and seizures’ of medicine’ and ‘Unequal protection’ compared to other drugs.”

Coyote: Trippet also had one key supporter: Dr. Tod Mikuriya, a psychiatrist who lived in Berkeley He was also a director of marijuana research for the National Institute of Mental Health. In 1967 he published a book titled Marijuana Medical Papers.” [Mikuriya’s brief stint at NIMH had ended in ’67. His anthology of pre-prohibition medical literature on cannabis was self-published in 1973.]

Trippet: Every county I would bring him to the stand and he would testify ‘Yes, I believe that she uses it legitimately.’ It made all the difference, because if I’d had no advocate, I’d just have been up there flailing around about my Constitutional rights.”

Coyote: When she lost at one level the appeal moved up to a higher court because she was claiming Constitutional rights… In the mid-1990s her argument for the right to transport marijuana for medical purposes was sent to the US Supreme Court.

Trippet: My papers went to the Supreme Court and they all read it. And of course I was denied a hearing on these Constitutional grounds. The idea is simple: you must be able to carry with you the medicine you can legally possess, or it’s unequal with every other medicine.”

Coyote: In 1996 Proposition 215 legalized medical marijuana in California but it left out one key element: it was still illegal to transport marijuana. [Prop 215 was also silent on distribution.]

Trippet: What about transporting? It wasn’t there. That’s because they [the primary drafters] thought ‘It’ll make us lose, people will think we’re smuggling.’ So they left it out.”

Coyote: But by this time Trippet had spent decades building the legal foundation for the transportation of medicinal marijuana. The California Supreme Court used her work to create what the justices called ‘The Trippet Standard.’ (Shot of federal court building.)

Trippet: Somebody had to argue it and include it, so I did. And they granted transportation as ‘the implicit right.’ Those are their words! Wow! Perfect!”

Coyote: The Trippet standard also established how much marijuana a person could carry based on their medical condition. It had taken three decades, a dozen arrests, and two years in various jails, but Pebbles Trippet had made it possible for California to have an entirely legal marijuana business.”

The segment ends with Trippet explaining why “to lose is a good thing… because if you lose, you have the opportunity to win higher for everybody. That’s where you set precedent.”

Trippet amplified her point to O’Shaughnessy’s: “Lawyers have largely been discouraged from pursuing appeals once their clients lose at trial or take a plea, since the probability of winning on appeal is slim, only two to three percent.. When Tony Serra discovered this disparity in his own practice, he told me, ‘Forget it. I want to win.’ He turned [his efforts] to winning at jury trial where there is no need to appeal.

“But the problem with that is that very few cannabis defendants go to trial —two to five percent. And even fewer win, and most can’t afford the appeal process. So the laws by and large have remained unchallenged for decades; the defense bar is trained in criminal, not civil, law. We have not built an infrastructure of lawyers schooled in civil constitutional challenges. So a marijuana challenge comparable to Roe v Wade eludes us and prohibition persists.

“I hold the lawyers responsible for this. Most defense lawyers rely on a statutory motion to suppress the evidence, based on no probable cause or lack of a warrant, or whatever —so they have nowhere to go once they lose on appeal. The 1538.5 suppression motion is the end of the line for appeals —unless constitutional rights are also argued.

“Usually on appeal lawyers use the suppression motion to get rid of the evidence, which I was instinctively opposed to because I wanted to bring out the evidence, not suppress it… Any lawyer could do the same thing but they are too afraid of losing their reputation on a futile or failed attempt, so they stop at the suppression-motion stage and don’t even try. That’s why I say ‘losing is a good thing.” If you’re incapable of accepting loss, you’re incapable of getting a win.

“When Prop 215 passed, I suddenly had new statutory rights, which I of course incorporated. They could not ignore someone with knowledge and staying power. Being ignored for years taught me how not to be ignored and to be affirmed instead.”