“My liaison to the medical marijuana community” is how District Attorney Terence Hallinan sometimes introduced me. “Public Information Officer” was the job title, and I gave the City and County of San Francisco their money’s worth. I returned every phone call and answered every email, and not just from the media types and pot partisans. More than half the calls directed to the PIO were from concerned citizens, many of whom expressed surprise when they got a call back from somebody at a government agency interested in what they had to say.

In 1996 Hallinan had been the only DA in California to support Proposition 215, the ballot initiative that legalized the medical use of marijuana. Implementation of the new law had been constricted by the “narrow interpretation” imposed by the prohibitionist Attorney General Dan Lungren. Kayo wanted me to help him implement Prop 215 in San Francisco according to the letter and spirit of the law. When it came to marijuana, he was still a Communist at heart.

Our plan was a literal and figurative pipe dream: San Francisco should grow its own! Organically! The Health Department could provide it at cost to medical users! Jobs for growers! Sanity in one city! “The cut flower industry used to be very big around South City,” Kayo recalled. “There are still some glasshouses standing.”

Back at the office I obtained a list of “Real Property Owned by the City and County of San Francisco.” SF’s holdings in other counties are mainly water and electrical right-of-ways, but there were some outliers. Thanks to a bequest, San Francisco owned a “park/library” in Fresno County and another in Kern County. Too far away and not suitable for cannabis cultivation. There was Camp Mather near Yosemite, but most of all we’ve got to hide it from the kids. But on San Mateo County, San Francisco owned, in addition to the airport and the Log Cabin Ranch School, a 484-acre jail site.

One afternoon in March I drove down Skyline Boulevard to visit the San Bruno jail (as it was called, although it was SF’s). The property included a 12-acre organic farm tended by inmates and run by a woman named Catherine Snead. She said she had a waiting list of 50 inmates hoping to join her crew. Many at the jail had Hep C and/or were HIV-positive. “It’s not a healthy population,” Snead said, “But working here with us, they become healthy. What this really is is horticulture therapy.”

The farm produced whatever was in season and supplied the jail with fresh fruit and vegetables Surplus produce was distributed to people in need through the police department’s Bayview and Mission stations. Captains Harper and Ross were among Snead’s fans; ditto Chief Fred Lau and Commander Heather Fong (who would succeed Lau). Snead said the farm had employed 3500 people since 1992. “Most people leaving the jail are homeless and the shelters are full of drugs,” she lamented. She tried to arrange housing, help former inmates get off probation and parole.

Sheriff Mike Hennessy let Snead bring ex-offenders out to the jail to work side-by-side with the prisoners (for better pay). Hennessy had done a recidivism study that documented the benefits of Snead’s “horticulture therapy.” But she didn’t think he’d go for a marijuana garden, no matter how secure she could make the site. “Not a chance,” was her assessment.

Another option I discussed with Kayo was Hunters’ Point Naval Shipyard, which had been decommissioned along with Treasure Island and the Presidio. Kayo was of the opinion that there had been a divvying up of the spoils, with Nancy Pelosi getting to decide the fate of the Presidio and Willie Brown making the big decisions on Hunters Point. “The Supervisors have some sway on Treasure Island” he said. He wanted T.I. to be the site of housing for those people living on the streets of the city or in vehicles who could fend for themselves, and a mental health hospital for the homeless who could not. I thought his idea was great but the real estate would prove too valuable. Kayo said, “You have no idea how miserable Treasure Island gets when the wind comes whipping off the bay —which is half the time.” He had me draft a press release emphasizing the suitability of T.I. for housing and treatment of San Francisco’s homeless population.

The city’s Treasure Island Development Authority was executive-directed by Annemarie Conroy, a rightwing former Supervisor. (A young woman named London Breed was employed by the TIDA as a “development specialist.”) Matier & Ross reported:

“Annemarie Conroy Willie Brown’s commodore of Treasure Island has two words for District Attorney Terence Hallinan’s much publicized ideas of setting up drug rehab centers out on the island. ‘No dice.’ And those are the nice words…

“‘Here we are, getting ready to hold a pre-bid conference for people interested in developing the island, and he comes out with idea of dumping drug rehab programs our here,’ Conroy fumed. ‘It’s a public relations nightmare.”

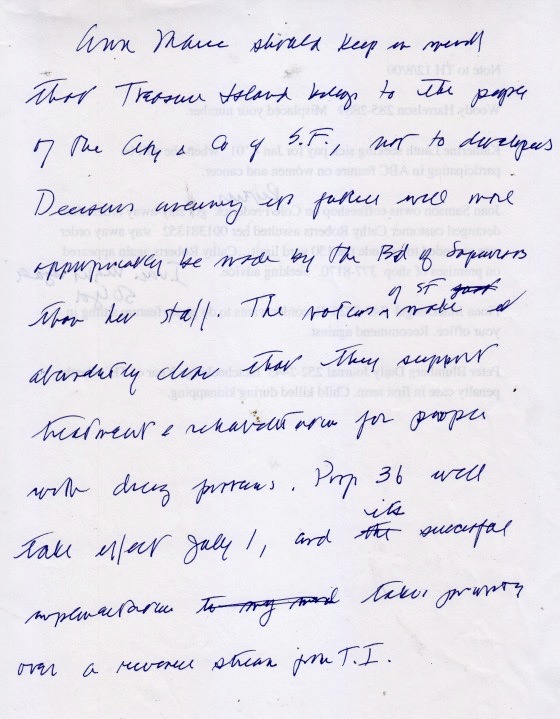

“Hallinan isn’t showing any signs of backing down. ‘Annemarie should keep in mind that Treasure Island belongs to the people of San Francisco not the developers,’ Hallinan said. ‘It’s use will be decided by the Board of Supervisors not by Conroy or her staff…”

“It turns out that Hallinan’s office leases space out on the island for a check-bouncing program. ‘Those leases are up this week,’ Conroy told us ‘and I’m sending him a termination notice right now. As far as I’m concerned he’s been voted off the island.”

But I digress. Kayo figured that Willie Brown (dubbed “Da Mayor” by Kamala Harris) would have to approve any plan to grow medical marijuana at Hunters Point. He planned to pitch Brown on the idea, but didn’t want to request a meeting at which it would be high on the agenda. The farm we had in mind would grow fruit and vegetables for the community; marijuana would be a small sideline in terms of acreage. My friend Scott Madison had leased a commercial kitchen at the Point and I drove out there to interview him about the internal politics and the land itself. (There is some excellent topsoil and it is the sunniest spot in San Francisco.) I met with Espanola Jackson, a very sharp leader of the Black community and attended meetings of the Bayview NAME TK, to hear people from the neighborhood express their hopes for the base. I gave Kayo news clips about the Russians growing hemp at Chernobyl to leach radioactive toxins from the soil —all in preparation for his appeal to the man with decision-making power, Willie Brown, Jr.

They had a long, complicated relationship. Kayo once told me that he knew Brown “through the DuBois Clubs,” a political group set up by the Communist Party to attract radical young people who would not have joined the CP itself. Kayo had been a founder and was a leader of the DuBois Clubs in the Bay Area in 1964 when Willie Brown, a 29-year-old defense attorney, made his second run for state assembly from the district comprising Hunters Point. He had lost in ’62 by 600 votes. As Wikipedia tells it:

“The key to Brown’s 1964 campaign was voter registration in the black neighborhoods. Brown’s registration drive in the Eighteenth Assembly District netted 5,577 new Democratic voters in three months, a staggering number for the era. Many of the frontline troops registering voters had been among those arrested in the civil rights demonstrations. Terence Hallinan organized his radical friends from the W.E.B. Du Bois Club into the ‘Youth Committee for Assemblyman Brown,’ which worked primarily on voter registration. Hallinan kept the youth committee active for two years, helping Brown to permanently harden his base of support in his district.”

That was then —another millennium. By Y2K Willie Brown had it in for Terence Hallinan and was trying to blame him for all the poverty and mental illness plaguing the streets of San Francisco. I don’t know the occasion on which their paths crossed and Kayo pitched the plan for a farm at Hunters Point. Back at the office he told me it was thumbs down. Kayo said, “I told him what I had in mind and he seemed to be listening with interest. But then he said, ‘Where I come from African-Americans were relegated to doing agricultural labor. I would be very careful if I were you about telling African-Americans they should aspire to do farm work.'”

It was the perfect squelch, because nobody was more Politically Correct than Terence Hallinan. That night I told my astute wife how our utopian dream had been shot down. She said, “He could have told Willie Brown that his stepdaughter and Coppola’s daughter and all their Pacific Heights friends think that nothing is more chic than organic farming.”

The private-sector option

Terence Hallinan’s pro-marijuana perspective led some growers from outside the city to contact the DA’s office seeking the green light for projects in San Francisco. Santa Rosa’s premier pot lawyer, Chris Andrian, wrote Terence on behalf of Paul Klopper and Alan Silverman, who were growing the herb in Guerneville and running a dispensary called The Farmacy:

“My clients have asked me to send this letter of introduction and proposal which we believe answers the question, ‘How can the City and County of San Francisco provide medical marijuana to a bona-fide patient and still remain within the scope of Proposition 215?’… We believe the answer to the City’s dilemma is in the establishment of a ‘patient-controlled cultivation facility’ where the patient maintains control and possession of the marijuana being cultivated. Here, the patient enters into a lease/rental and power-of-attorney agreement with a private not-for-profit agency, such as the Farmacy, wherein the agency provides the cultivation space, the use of its horticultural lights and growing supplies, and manages the daily caretaking functions for the patients’ plant(s). Upon maturity, the patient takes physical possession of the harvest and dried cannabis plant, roots and all.”

Hallinan gave the go-ahead and Klopper leased a building on Mission Street in the Excelsior District. Part of my job was to drop by the dispensaries unannounced and make sure no pesticides were in evidence. At Klopper’s site tables had been built out and lights installed by a skilled young man named Erich Pearson, who would go on to found Sparc, one of San Francisco’s most successful dispensaries. His relationship with Paul Klopper ended in a bitter falling out, as so many relationships would as the outlaw movement turned into the legal Industry. Money changes everything.

Another detailed cultivation proposal came from Ed Rosenthal, the famous “guru of ganja,” who owned a warehouse in Oakland where his employees were growing a large number of clones unbeknownst to the authorities. Having to conceal his operation after the passage of Prop 215 was an affront to Ed, who had devoted 30 years to the cannabis cause and wanted to reap the colas of victory.

“I propose to set up a large farm to produce standard grades of medicine under sanitary conditions,” he wrote. “It would be in a greenhouse or an enclosed building in San Francisco and it would produce a sizable portion of the medical marijuana used in San Francisco and Oakland. As an approved business, it would be subject to inspection and regulation… Existing clubs in the city have expressed support for a stockholder, for-profit economic model, and are willing to invest significantly in this venture… By creating a legitimate, sizable farm for production of medical marijuana, standard varieties could be grown consistently to produce the same percentage of medicine… A standardized and legitimized farm has great potential as an important research facility…”

Kayo invited Ed to the office for a meeting, after which I gave him a drive-by tour of the four extant- but-dilapidated glasshouses I had located by driving methodically (and almost compulsively) around the southwest quadrant of the city. If Ed contacted the owners (I had given him info from the Assessor), nothing came of it, and he wound up investing in a dispensary on Sixth Street, the Harm Reduction Center, that had room for a large grow under lights in the basement. That venture ended with a raid by DEA agents on February 12, 2001, the day that DEA Administrator Asa Hutchinson was in San Francisco to address the Commonwealth Club.

Early that evening, as concerned citizens were arriving at the classy Commonwealth Club’s Market Street entrance to hear the DEA chief, many stopped to listen to District Attorney Hallinan on the sidewalk with a bullhorn, denouncing the raid to a crowd of pot partisans and defending the proprietors of the nearby Harm Reduction Center. “This is a decision to be made by the voters of California and the people of San Francisco,” Terence declared.

Upstairs Asa Hutchinson said the arrests on Sixth Street (which the DEA conducted without notifying the San Francisco Police Department) were part of the Bush Adminstration’s “War on Terror.” The President was pushing a new line: “Terrorists use drug profits to fund their acts of murder. If you quit drugs, you join the fight against terror in America.” Hutchinson was cut off by cries of “Liar!” after claiming, “Science has told us so far there is no medical benefit from smoking marijuana.”