The treatment was unconventional. People addicted to everything from alcohol to opioids were given the option of using marijuana to help deal with withdrawal symptoms from their former drugs of choice. But nearly a year after the facility, a Los Angeles-based rehab center known as High Sobriety, opened its doors, a consultant to the operation started to notice problems.

“It was like walking into a cloud of smoke,” Sherry Yafai, the facility’s new director of research and development, told Business Insider. That’s no longer the case, according to Yafai, who took on a leadership role at the facility roughly a year after it opened and made some major changes to its treatment protocol.

Her changes hint at a tough reality about the use of cannabis as medicine. Although marijuana is being increasingly recognized for its potential health benefits, using (and dispensing) it remains an inexact science that can be further complicated by stigma and misunderstandings about drug use.

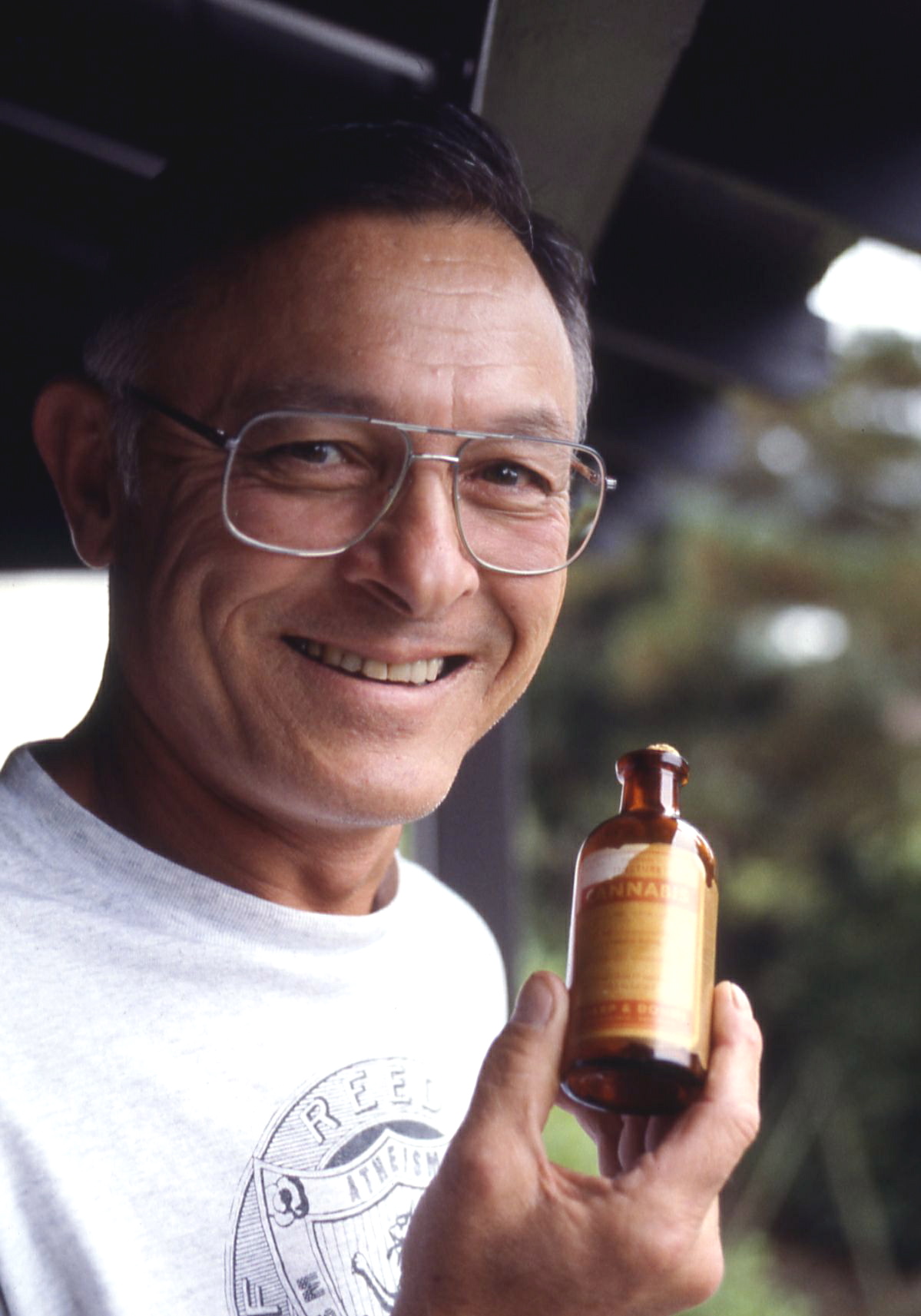

Created by Joe Schrank, a trained social worker from New York, High Sobriety was founded as an alternative to the traditional abstinence-based rehab model, which Schrank says is heavy on spirituality and religion but low on science and compassion.

“Abstinence-only drug education is about as effective as abstinence-only sex education,” Schrank told Business Insider.

Schrank ran High Sobriety in Los Angeles for a little over a year before he decided to leave after an internal dispute broke out. He’s currently based in San Francisco, where he is operating a new rehab facility based on the old High Sobriety model — if you want to use marijuana, you can.

“I like to remove anything someone’s going to potentially hurt themselves with. That’s why I’m a weed advocate,” Schrank said.

Yafai also believes that cannabis has a place in addiction treatment, but she disagrees on the details of how and when it is dispensed to patients.

Since Schrank’s departure, Yafai has made major changes to High Sobriety.

Smokeable marijuana is no longer allowed on the premises. Instead, patients may use cannabis oils, creams, or edibles — but they are not allowed to carry them or keep them at home.

Cannabis products are recommended “just like any other medication,” said Yafai, citing the examples of methadone and buprenorphine, which are prescribed to be given to patients addicted to opioids at a specific time of day. Also, all High Sobriety patients must go through 30 days of detox without cannabis.

“The way we try and medicate patients is so they’re not high all day,” Yafai said. “I want people to function.”

After 30 days of sobriety, patients meet with Yafai, who decides what type and dose of cannabis-based product could help them. She might recommend using a cream made with CBD (the non-psychoactive component of marijuana) for pain, or she might recommend a THC-based edible at night for sleep. The patient then takes that recommendation to a licensed dispensary where they can be purchased.

These changes are designed to address some of the problems that Yafai said she saw at the facility when she was working as a consultant.

When she’d walk onto the facility grounds, for example, she’d see smoke everywhere and find patients who were “high for the majority of the day.” As a result, patients were not addressing the underlying issues that may have brought them to High Sobriety in the first place, such as depression or other forms of mental illness.

“I found a group of individuals who were not able to engage in a conversation and were just actively smoking in front of me. I don’t think that’s appropriate. When you’re dealing with life and death with a group of 20-year-olds, you can’t get that concept across or expect them to deal with anything — let alone remember anything — when they’re high.”

Now, she believes her patients are more engaged in the various components of therapy offered at High Sobriety, whether it’s mutual help meetings like those offered by Alcoholics Anonymous or individual work with a psychologist to address issues like anxiety and PTSD. Cannabis plays a complementary role in those aspects of recovery, said Yafai.

“I can teach patients how to use cannabis so that when you leave High Sobriety, you can walk into a facility where you can pick a product that helps you address your issues,” Yafai said.

Schrank maintains that if people want to use marijuana, they should be free to use as much as they need.

“People lead productive lives with cannabis,” Schrank said. “And the truth is this stuff is probably safer than Doritos.”

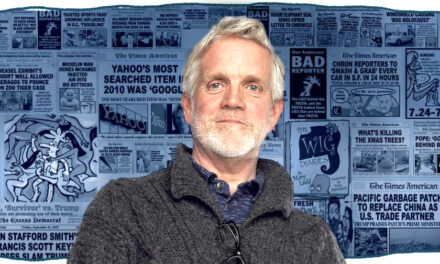

Schrank’s new facility, called Remedy Recovery, is headquartered at a loft space in San Francisco’s China Basin neighborhood, which he envisions eventually being used as a community space. Schrank and a new a team of social workers — plus a new Remedy Recovery CEO who also has his own private equity firm — currently oversee six patients in an apartment complex nearby.

He hopes the new center will operate similar to the way High Sobriety once did. But he said doctors will play a prominent role.

“If the doctor’s counsel with cannabis, whether it’s smokeable or edible or whatever, is ‘OK, take this much,’ we’ll say, ‘Thank you doctor, we’ll follow your counsel.”

Yafai, who calls herself a cannabis clinician and is a member of a nonprofit called the Society of Cannabis Clinicians, said that wasn’t happening enough at High Sobriety before.

“There wasn’t another MD on board giving cannabis medications,” she said.

Having a physician on board to dispense marijuana and make product recommendations could be vital for recovery centers looking to incorporate cannabis into their models. Several studies suggest that marijuana could play an important role in treating pain and helping people recover from addiction to other drugs like nicotine and opioids, but none have yet tested out High Sobriety’s model.

In contrast, thousands of rehab facilities across the US operate using abstinence-only approaches such as the ones outlined in the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous with scant peer-reviewed research behind them.

Yafai said she’s been “thrilled” with the changes she’s seen in her patients at High Sobriety over the past few months. But she also worries that other facilities may try to emulate the High Sobriety model without enough scientific guidance.

“I think other places will try to do this, but without the guidance of a cannabis clinician they will fail,” Yafai said.

http://www.businessinsider.com/facility-marijuana-for-addiction-shakeup-2018-7