By Darmon Richter 29 September 2013

So as it turns out, growing and smoking cannabis is completely legal in North Korea. Encouraged, even. Here’s the story of how I found out… and then ended up indulging in the ‘special plant’ with an officer from North Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The discovery came during my recent tour of Rason in North Korea, at the time of the 2013 Korean Crisis. The DPRK was – potentially – poised on the brink of nuclear war with the South, with Japan, the US, et al., and I was hanging out in a small port town somewhere near the Russian border.

As is generally the case with tours to North Korea, I had visited as a part of a group. However, this was no ordinary group. Rather than offering the tour to members of the public, the team at Young Pioneer Tours were putting on a ‘staff outing’ of sorts… and I’d been invited along for the ride.

In true Korean style, YPT’s counterpoints in the DPRK felt obliged to match this show of seniority (as they perceived it) by sending one of their own high-ranking officials to lead our group: a ‘Mr Kim,’ from North Korea’s own Ministry of Foreign Affairs [1].

The details of the tour – as well as my own reflections on visiting the country at a time of seemingly imminent war – are the subject of my post on the 2013 Korean Crisis. What follows here, are the parts I left out.

Rason Market

Having a high-ranking North Korean official in our team unlocked doors for us; doors which usually remained firmly closed to tourists. On the standard North Korea tour package, a group will be allotted two Korean guides. It’s their job to keep you in line – a job which they usually handle with a cheerful yet firm approach:

Don’t go in there… Don’t photograph this… I can’t answer that… but wouldn’t you rather hear about our Dear Leader’s birthday celebrations?

Fearful of getting into trouble with their superiors, most North Korean guides err on the side of caution. They’ll impose a blanket ban of no photography from the tour bus, and if there’s ever any doubt the answer will invariably be “no.”

Our Mr Kim was able to speak with confidence on behalf of the nation, though. When he answered in the negative it was absolute; but there were plenty of other occasions when he’d be able to flash his ID card, or call ahead to authorise our entry into restricted areas.

The first of these restricted areas we were to visit was the local bank.

As we arrived, two Korean girls in make-up and high heels were struggling to carry a sports bag, heavy with banknotes, to the back of a waiting taxi. Inside the building security seemed slim, and rather than through a reinforced glass counter, business was conducted in one of a series of simple offices.

We queued up to change our Chinese Yuan into the local currency: the North Korean Won. I was aware just how unusual this was; the vast majority of tourists in the DPRK will spend Chinese or US currency, and are restricted from handling (or even seeing) the local notes. With an exchange rate of roughly â’©1,450 to ÂUKP1 (or â’©900 to $1), the notes were numbered into the thousands. Different denominations bore the face of President Kim Il-sung, an image of the president’s birthplace at Mangyongdae-guyok, the Arch of Triumph in Pyongyang and, on the â’©200 banknote, a likeness of mythical flying horse, Chollima.

Carrying roughly one quarter of a million Won between us, we headed down to the market. Rason’s market has been off-limits to tourists for many years now, after an incident in which a Chinese tourist was pick pocketed. He had reported the theft to his embassy, and pushed for recompense from the North Korean tourism industry; and as a result of the international drama which followed, North Korea decided it would be simpler not to let foreigners enter the market at all.

Mr Kim made a few calls, and pretty soon we were heading inside. We were urged to leave our wallets on the bus, instead taking a handful of local banknotes concealed in an inside pocket. Cameras were also strictly forbidden. I’m not sure exactly how Mr Kim got us inside, or how legitimate our visit was – but he made it very clear that there was to be no evidence of our expedition.

The market was a sprawling maze of wooden tables, overflowing with everything from fruit to hand tools. Immediately upon our entrance, a wave seemed to move through the crowd as several hundred pairs of eyes turned to assess the intrusion. If the streets of Pyongyang and other North Korean cities may appear empty, even desolate at times, this place was the exact opposite… and I was struck by the sense of having stumbled across that fabled thing which seems so hopelessly impossible to find: the ‘real’ North Korea.

As our group separated, moved through the stalls and began to mingle with the bemused locals, our Korean guides floated about us like owls on speed. It’s impossible to guess the punishment that would await them (and possibly, by association, their families) were they to lose sight of their Western wards in this forbidden location. Luckily for them however, we didn’t exactly blend in.

It was interesting to see the range of reactions that our presence elicited from the unsuspecting people of North Korea. Some gasped in shock, covering their mouths and nudging their friends to look at us; children waved, giggled, shouted “hello” and then ran away; vendors called and beckoned us to browse their wares. Everywhere I looked there was a movement of heads turning quickly away – everybody here wanted a good look at the strangers, but most couldn’t hold our gaze.

One elderly man in a tired military uniform followed us through the market, scowling from a distance. Several times I felt tiny hands patting at my trouser pockets, then turned, to see dirty-faced children peering out from the crowds. On one occasion I was confronted by an actual beggar – it’s still the first and only time I’ve seen a North Korean ask a foreigner for money, and something which the DPRK leadership does its absolute best to stamp out.

I yearned in pain for my camera, my shutter finger itching like a phantom limb.

At one point we bumped into a few of the girls from the massage parlour we’d visited in Rason. They stopped browsing to chat with us, and, for just the briefest of moments, I could almost have believed this wasn’t the strangest place I had ever been.

Things were to get a whole lot stranger though, as we approached the covered stalls at the heart of the market. While the outer yard had been stocked with fruits, vegetables and all manner of seafood, Rason’s indoor market is a repository for every kind of bric-a-brac you could care to think of… and most of it imported from China.

Shoes, toys, make-up, lighters, DIY tools that look around 40 years old, clothing, military uniforms (which we were forbidden from buying), spices, chocolates, soft drinks, dried noodles, bottled spirits, beer and a whole aisle lined with mounds of dry, hand-picked tobacco.

We were just walking past the tobacco sellers when we spotted another stall ahead, piled high with mounds of green rather than brown plant matter. It turned out to be exactly what we first suspected: a veritable mountain of marijuana.

In the name of scientific enquiry, it seemed appropriate to buy some… and the little old ladies running the stall were happy to load us up with plastic bags full of the stuff, charging us roughly ÂUKP0.50 each.

As it turns out the “special plant,” as they refer to it here, is completely legal. We decided to test the theory, purchasing papers from another stall before rolling up and lighting comically oversized joints right there in the middle of the crowded market. Bizarre as the situation was, it seemed a reasonably safe move – and with several hundred people already staring at us, we weren’t going to feel any more paranoid than we already were.

At another stall we bought live spider crabs for our dinner, before leaving the market to continue the grand tour of Rason – with just one difference. From this point onwards, every time our group was walking on the street, sat in a park or being shown around some monument or other, there would be at least two fat joints being passed around.

Later that day, we visited a traditional Korean pagoda situated in a nearby village.

“This monument celebrates the fact that our dear leader Kim Jong-il stayed in this very building during one of his visits to Rason,” our Korean guide was telling us.

“Far out,” someone mumbled in reply.

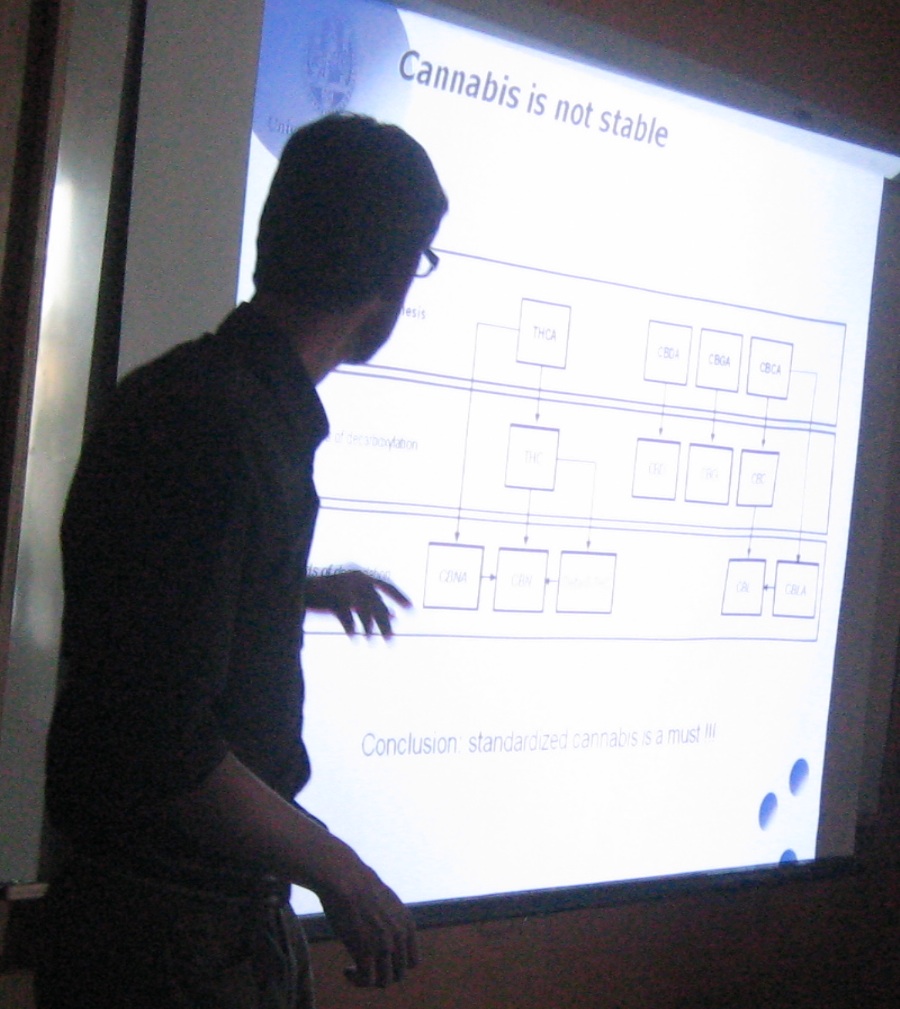

Illegal Drugs in North Korea

It has been reported elsewhere that the DPRK has a growing problem with crystal meth. Being relatively cheap and straightforward to produce, it seems to be the hard drug of choice in North Korea.

Cannabis on the other hand, is not even considered a drug. Known in Korean as “ip tambae,” meaning “leaf tobacco,” it is grown in large plantations before being handpicked and dried for consumption. Enjoyed primarily by the working class and service industries, this ‘special plant’ is praised for its therapeutic properties. It’s often promoted as a natural and healthy way to relax, as well as soothing aches and pains resulting from hard physical work or active military service.

This terrific piece first appeared as On Smoking Weed in North Korea on The Bohemian Blog. Reprinted with permission.