By Fred Gardner —O’Shaughnessy’s Spring 2004

“Any pain-management training that does not have information about cannabis is committing malpractice.” —Claudia Jensen, MD

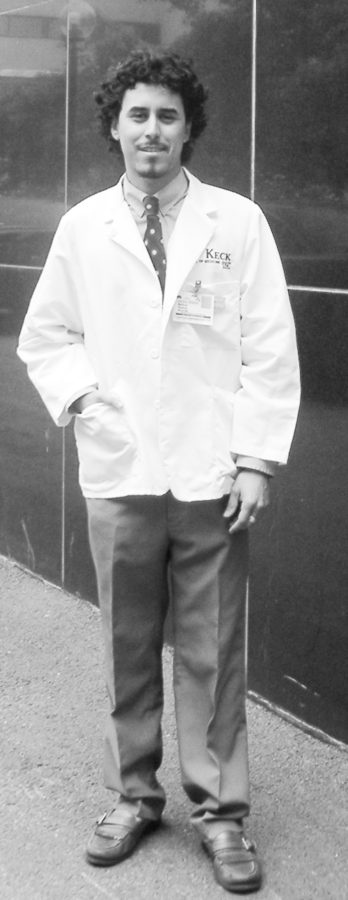

On Feb. 13 students and faculty from the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine put on a half-day program devoted to the clinical uses of cannabis and the relevant pharmacology. Some 30 first- and second-year medical students attended the history-making event in McKibben Hall, which was organized by Rolando Tringale, a second-year medical student, and Claudia Jensen, MD, a Ventura pediatrician who is an Instructor in the Department of Family Medicine.

Jensen teaches “Introduction to Clinical Medicine,” in which first-year students learn how to take a patient’s history and conduct a physical exam.

Since the Fall semester of 2001 Jensen has spent a full day in the ICM class talking about cannabis and bringing in patients for students to interview.

“They’re open-minded and well educated,” she says of her students. “And they actually go on to teach their colleagues the truth about cannabis. That’s why Rolando wanted to do this presentation.” (Tringale had taken Jensen’s ICM class last year.)

The Feb. 13 program started with first-person accounts from patients. Jensen had invited Ishmael Gayes, “a paraplegic —a very beautiful, intelligent, spiritual black man who was shot in the back over a woman when he was 17;” chronic pain patient Lisa Cordova Schwarz, LVN; and glaucoma patient Jim Carberry. Bill Britt, an activist from Long Beach who has post-polio syndrome and epilepsy, also described his use of cannabis.

Joseph Miller, PhD, Associate Professor of Cell and Neurobiology, discussed the pharmacology and biochemistry of the body’s own cannabinoid receptor system, which is activated by THC and other compounds in the plant.

Miller’s research has been funded over the years by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). “He’s not a medical marijuana proponent,” says Jensen,“he’s not in the movement. He’s just an honest man with a balanced, truthful perspective about drugs who was willing to be a speaker.”

Associate Professor of Psychology Mitch Earleywine, PhD, discussed the question of safety. Earleywine, the author of “Understanding Marijuana” (Oxford, 2002), said that medical users could minimize negative consequences by vaporizing instead of smoking. Earleywine also advocates “keeping dosage at a level that relieves symptoms but doesn’t create any impairment” and “monitoring for any signs of craving that might indicate tolerance or withdrawal.”

Earleywine has found that “the people who run into dependence problems with cannabis are the ones who are drinking a lot of alcohol.” He recommends that medical cannabis users avoid alcohol consumption.

Attorney William Logan explained Proposition 215 —now California’s Health & Safety Code Section 11362.5— and recounted the court rulings that affect its implementation.

Jensen’s talk —“Integration of Cannabis Treatment into the Practice of Medicine,” a version of what she teaches the first-year students— delved into questions such as:

• How do you tailor a history and physical to a medical marijuana patient?

• What dose and strain and route of administration should a patient use?

She also discussed “the advantages and disadvantages of having medical marijuana patients in your practice.”

Jensen’s Approach

Regarding dose and route of administration, Jensen says, “I make a decision based on what their medical problem is, the duration of the effect that they need, the strength of the effect that they need, and the quality of the effect that they need. And then I advise them what to use based on what other patients have taught me. One of the biggest problems is that I’m not getting this information from scientific sources, I’m trusting the patients. This is a unique field of medicine, where the doctors are actually learning from the patients.

“Instead of relying on data from placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials conducted in some far-off academic ivory tower, it’s from talking to the patients and finding out what they do and how does that work?

“It’s folk medicine with a trained listener who applies principles of science. Basically, I’m doing my own studies.”

Indica or Sativa?

Jensen regrets that California physicians have no way of analyzing the actual cannabinoid content of the various strains patients are using. “Based on what I’ve learned from patients,” says Jensen, “The Indicas seem to be better for pain, for insomnia and to calm their nerves. The Sativas seem to work better to elevate mood and energy levels. But I see a higher incidence of patients who are nervous and have anxiety and rapid heart rate and also a high incidence of heartburn.

“I talk to them about how to pay attention to what they’re using. I tell them, “don’t just buy any street weed. Find out, what are you smoking? White widow? Chronic? Hindu Kush? Romulan? Know the name of it and try to develop your own quality control standards because we can’t go to a textbook for that.”

To Tell the Truth

“How many of you use marijuana?” Jensen asked. She says, “Probably seven students raised their hands. I told them ‘I am very proud of you having the courage and the integrity to tell the truth, because that’s what this conference is about.’” Jensen also asked how many had or knew somebody who had a condition treatable by cannabis. About 90% raised their hands.

Physicians can help patients overcome social ostracism and embarrassment, says Jensen. “When a physician takes responsibility for advising a patient on cannabis as a medication, it helps legitimize for the patient that what they’re doing is okay.”

Physicians themselves face ostracism for issuing cannabis approvals. “There’s this unspoken attitude,” says Jensen, “—‘she’s not a real doctor, she takes care of cannabis patients.’ I’m the ‘pot doc.’ On the other hand, I get referrals from all the local doctors —psychiatrists and family medicine and oncology doctors sending me patients because they don’t want to treat them.”

Jensen thinks that many physicians who themselves use cannabis are “uncomfortable writing notes because they don’t want to attract any attention to themselves. They don’t want to take the chance because somebody might come and say ‘Let’s test your urine.’ There is a significant proportion of physicians who smoke pot surreptitiously. They’re afraid to write notes because they don’t want to be in anybody’s database. So, the whole thing boils down to patient advocacy vs. social ostracism. Cannabis-using physicians are afraid to come out of the closet. And it’s really a problem—it’s harmful to the patients.”

Jensen laments the “information vacuum” in which clinicians monitor their patients’ use of cannabis. “This is the only field of medicine where the patient routinely has more knowledge than the physician. As a scientist, that’s a bitter pill to swallow. I can’t go to a reference textbook. Where do you go for information on something that you’re not allowed to have information on?”

Another disadvantage: lots of paperwork.

Jensen urges students to “remember what you went into medicine for is to be an advocate for patients. You have to have the courage to do that even if it’s not socially acceptable.”

She hopes that patients will “educate their famiy and friends —tell them the truth— so they can use this as medication without sneaking around in the back room.”

Jensen had invited —after getting administrative approval to do so— Richard Davis, proprietor of the USA Hemp Museum, who brought samples of hash, hash oil and other cannabis-based products, as well as some plant strains (in jars), providing, for some of the students, a first exposure to the once-prohibited herb.

Jensen says that the USC administration has been supportive of her efforts to introduce cannabis into the curriculum. Althea Alexander, Clinical Instructor for Educational Affairs, attended the Feb. 13 conference and expressed gratitude to the patients who took part. Alexander regretted that the event had been scheduled for the getaway day of President’s Day week-end; there would have been a much heavier turnout, she said, on an ordinary Friday.

Jensen hopes that next year the conference will be held in October, “when the students are freshest,” and that it will be a requirement. (This year’s was not offered for credit.) Jensen had an insight about “elective” classes when she was in med school at the start of the 1980s. “I took an elective on ‘Sexual Desensitization’ and the only students who went to it were the students who were comfortable with sexuality. All of the really up-tight people avoided it. So I don’t think cannabis should be an elective. I think it should be required training.”

CME class coming soon?

Jensen has also given thought to developing a continuing medical education program for physicians, none of whom learned a thing about cannabis in medical school. (Doctors are obligated to earn a certain number of CME credits annually.) She has proposed to the administration that USC offer a CME course on cannabis. Professor of Clinical Instruction Alan Abbott told her he was amenable and would look into possible funding.

Jensen thinks her colleagues in the medical profession will take steps to educate themselves on the subject of cannabis only when they are obligated to. And she has a strategy to obligate them. “The Medical Board of California has dictated that physicians have to take 12 hours in pain management in order to maintain their licensure. My position is that any pain management presentation that any physician takes is inadequate if it does not include discussion about cannabis and cannabis compounds. The Medical Board should take the position that cannabis teaching needs to be integrated into those pain management sessions that physicians are already required by law to attend.”

Jensen is a pediatrician whose special interest is in cognitive function and development. She branched into treating adults as a result of her interest in cognition. She says that with every patient she tries to figure out “the habits that are keeping them sick.”

Jensen spends an hour seeing each new patient. She learned recently that she is under investigation by the Medical Board for allegedly providing substandard care to three ADHD patients (whose cannabis use she approved).