By Fred Gardner —O’Shaughnessy’s Spring 2004

Since November 1996, California law has authorized physicians to recommend cannabis in the treatment of a wide range of serious medical conditions. As of Spring 2004, by O’Shaughnessy’s’s estimate, at least 100,000 patients have obtained physician approvals to do so.

We extrapolated from the number of Oregonians —more than 10,000— who had obtained physician approval as of Jan. 1, 2004. (The state of Oregon maintains a registry of medical marijuana users and physicians who authorize its use; California does not.)

Twelve doctors associated with the California Cannabis Research Medical Group—all but one from the northern part of the state— have issued approximately half of those approval letters.

Proprietors of dispensaries in Oakland and San Francisco report a marked increase in approvals issued by non-CCRMG doctors following a recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Conant v. Walters case.

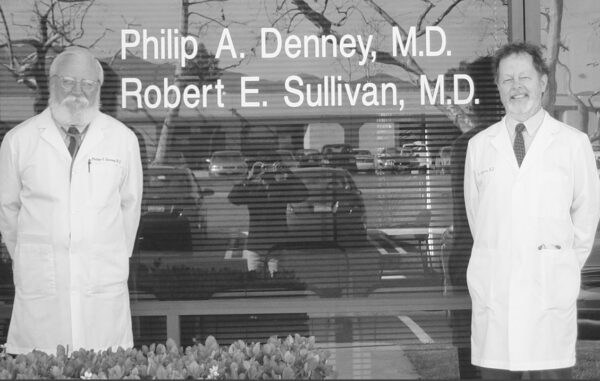

Philip A. Denney, MD, calls the Conant decision “a key factor” in his decision to open an office in Orange County.

The background

In December 1996 Drug Czar Barry McCaffrey and other federal officials threatened to revoke the prescription-writing licenses of California doctors who discuss cannabis as a treatment option with their patients.

UCSF AIDS specialist Marcus Conant, MD, and co-plaintiffs immediately sought an injunction to prevent the government from carrying out the threat.

“The war on drugs has become the war on physicians,” said co-plaintiff Virginia Cafaro, MD. But the tide was about to turn with respect to cannabis.

In April 1997 federal judge Fern Smith issued a temporary injunction protecting Conant and his fellow physicians from the federal threat. In 2000 federal judge William Alsup made the injunction permanent.

After the Bush Administration challenged the injunction, the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals upheld it in on First Amendment grounds: a doctor and patient discussing the medical use of marijuana, the Court ruled, are exercising a constitutional right to free speech.

In October 2003 the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the 9th Circuit decision. The permanent injunction became more permanent. [And isn’t it just like The Man to go around calling his evanescent institutions “permanent?”]

Denney to Orange County

On Feb. 9, Philip A. Denney, MD—who formerly practiced in Loomis, a town East of Sacramento— started seeing patients at a “cannabis evaluation practice” in Lake Forest, a city at the intersection of Freeways 5 and 405 in Orange County.

If the demand for cannabis consultants in Southern California is as great as Denney anticipates, he hopes to interest other physicians in the new specialty, which he defines as “determining whether a patient has a serious medical condition that could be treated safely and beneficially with cannabis.”

Denney recruited Robert E. Sullivan, MD, a former associate in Sacramento, to join him in Orange County.

Denney says that even 100,000 patients represents “a very small subset of the population that could be helped by cannabis if knowledgeable doctors were available through-out the state.”

Denney says that “even 100,000 patients” estimated to have used cannabis medicinally in California “represents a very small subset of the population that could be helped by cannabis if knowledgeable doctors were available throughout the state.”

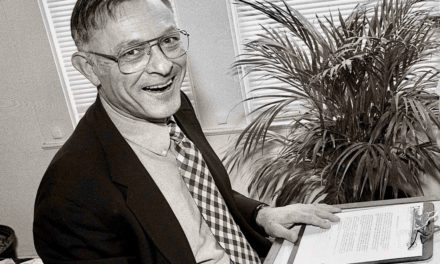

For most of his 27-year career Denney was a family practitioner. In the late 1990s, having become aware that doctors who approved cannabis in treating conditions other than AIDS or cancer were few and far between, he began studying the available medical literature and corresponding with specialists in the field.

In January, 1999, Denney opened an office in Loomis, specializing in cannabis evaluations.

“It was obvious when we had our practice in Loomis,” says Denney (the ‘we’ refers to his wife Latitia, who manages his office), “and people kept showing up from all 58 counties, that there was a tremendous need and demand throughout the state.”

A related need, according to Denney, is for a continuing medical education course that would bring California doctors up to speed on a subject they learned nothing about in Medical School.

Retreat, Advance

By the fall of 2002 Denney had approved cannabis use by some 8,000 patients and decided he would take early retirement. He transferred his practice (to William Turnipseed, MD) and devoted himself to reading, gardening, spending time with his family, and doing all the projects that needed doing on his hilltop spread in rural Greenwood. But Denney didn’t entirely withdraw from the fray —he helped defend colleagues under attack by the Medical Board of California, and he kept abreast of the medical literature and cannabis-related political developments.

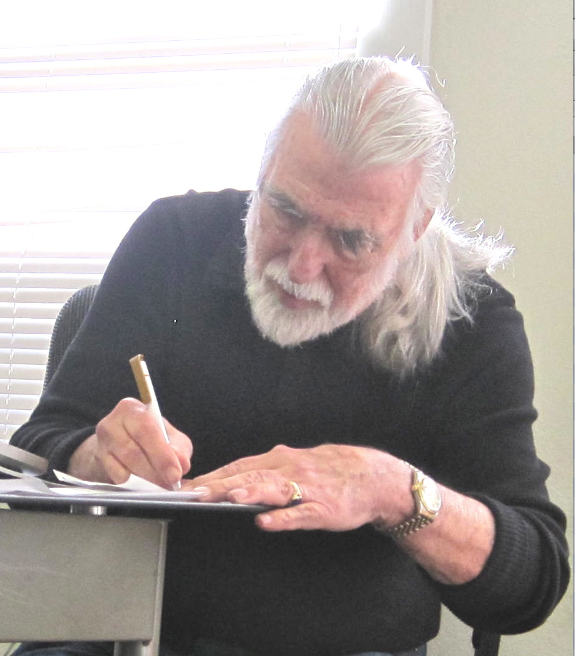

In May 2003 Denney appeared before the Board to protest the investigation of nine doctors specializing in cannabis consultations. “When you mention that nine investigations is a small number, you must consider the effect of those investigations on the rest of the physicians in California,” Denney reminded the Board. “The sanction of even one physician will have a dramatic impact on the practices of all others.” (Denney himself has never been investigated by the Board, a fact he attributes to the rigor with which he takes histories, reviews records, and conducts physical exams.)

“Patients come to a medical cannabis consultant seeking the answer to one specific question,” Denney explained. “‘Do I have a medical condition for which cannabis might be a useful treatment?’”

Denney also served as an expert witness in defense of Tod Mikuriya, MD —one of the cannabis specialists whom the Medical Board’s Enforcement Division had chosen to prosecute. Denney reviewed the relevant files and testified that Mikuriya had elicited enough information in each case to justify approval of continued cannabis use. Mikuriya’s practice should not be evaluated by the same standards as a conventional practice, Denney said. Prohibition had left the medical profession un-educated and frightened and law enforcement biased. “Patients come to a medical cannabis consultant seeking the answer to one specific question,” Denney explained. “ ‘Do I have a medical condition for which cannabis might be a useful treatment?’” Denney faulted the Board for not issuing guidelines relevant to such situations.

Denney calls the October 2003 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court to let stand the ruling in the Conant v. Walters case “tremendously encouraging.” The right of doctors to discuss all treatment options with their patients is protected by the First Amendment. Federal authorities are permanently enjoined from threatening or punishing California physicians who approve cannabis use by their patients.

Denney says that “more than 95%” of the patients to whom he has issued approvals had been self-medicating with cannabis before consulting him. The conditions with which they present, he estimates, are: chronic pain (50%); neurologic (20%); psychiatric, including ADHD and as a “harm reduction” substitute for alcohol (15%); gastro-intestinal (10%); other (5%).

Denney says none of his patients have reported serious adverse reactions or drug interactions. “Cannabis has been used medicinally for thousands of years,” Denney says, “and has a remarkably benign side-effect profile.”

Denney and Sullivan can be reached at 949-855-8845. Their new office is located at 22691 Lambert St. Suite 504, Lake Forest, CA 92630.