This started as “Roamin’ Noam in Marin,” AVA March 20, 1991.

Noam Chomsky, who lives in Lexington, Mass. and teaches linguistics at MIT, spends almost every weekend on the road, giving talks on political themes. His classes are scheduled towards the end of the week, so he also has Mondays and Tuesdays to carry the message (which is principally a critique of U.S. foreign policy). He takes off July and August.

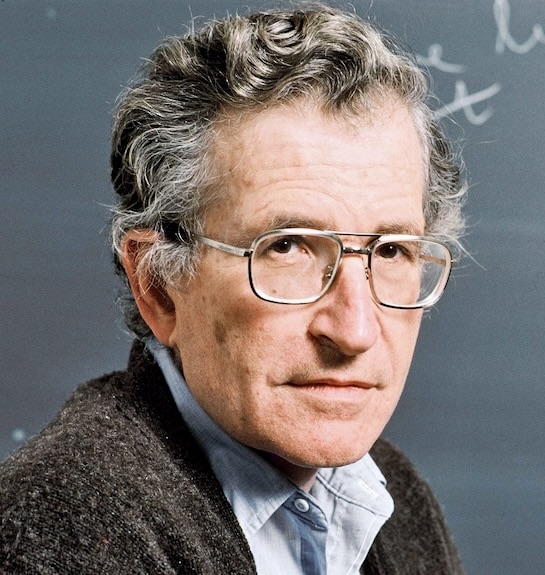

Chomsky is a thin, soft-spoken man in his late 50s, with graying wavy hair and light eyes that sparkle behind his glasses. This weekend he and his wife Carol were in the Bay Area. His talk Saturday night to a full house at the Berkeley Community Theater was a benefit for KPFA. His talk at the Victoria Theater in SF on Sunday at noon was a benefit for Barricada Internacional, the Sandinista newspaper. At 3 p.m. on Sunday he was at Bill Graham’s capacious house in Corte Madera, talking to 100 people who had paid $100 each to hear him –a fundraiser for the Marin Interfaith Task Force.

Introducing Chomsky, Graham said, “God bless the man for speaking his mind and standing behind what he believes in… You couldn’t believe the shit I heard from people this week [for lending his house for the event]: ‘How can you call yourself a Jew?'”

I interviewed Chomsky while driving him from Graham’s to his 7 p.m. appearance at the College of Marin. He held the tape recorder on his lap.

AVA: Could you explain your work in the field of linguistics? I once tried to read a book of yours on the subject and didn’t make much headway.

Chomsky: Let me suggest a book that might work: “Language and Problems of Knowledge,” which was a series of lectures that I gave in Managua under pretty adverse conditions. Things aren’t so great there. Also, I was talking in English because I don’t know a word of Spanish. And I was getting translated by non-professional translators, sort of phrase by phrase. But people were really sitting there listening carefully, and they did say they understood it, and people tell me the book’s very readable.

Basically what it’s about is that there is a distinctive human capacity which no other organism has at all, and which every human has normally. It’s virtually identical across the species and it seems distinctive to the species. Biologically, rather isolated properties like it don’t exist elsewhere. It’s at the core of human life and thought. And the question is: “What is it?” Well, it seems to be in the first place a very complex computational system with very specific properties. Rather surprising properties often. It’s a system of conceptual structures, again with very specific properties that are shared by everyone –all of this is known without any experience, every child grows into it. You just grow into it the same way you grow into getting bigger or going through puberty.

AVA: You learn language…

NC: You really grow language in your head the same way you grow your arms and your legs. If you’re not in the right environment it won’t happen, but if you’re in the right environment it will grow –you can’t do anything about it. It’s something that happens to you, and you end up with these quite refined and highly distinctive conceptual capacities and this astonishing capacity to express yourself in novel ways and over an unlimited range of situations. And the purpose of the subject is to try to find out what does that capacity consist of? How much of it is just part of our common nature? How much of it is modifiable by experience? Ultimately we would like to know things like: How does it relate to physical mechanisms? How did it originate in the species? How does it relate to other forms of human action? Similar things could be discovered about human moral and aesthetic capacities that haven’t been investigated seriously.

AVA: Like what?

NC: Well look, there’s a simple point of logic and that is, if people are capable of making systematic judgments in some area and they don’t have any evidence for it, then it’s got to be coming from the inside. So you and I can make systematic judgments about sentences of English. You never heard these sentences before but you’re understanding them right off; which means you’re making highly systematic and quite complex judgments about very intricate matters. You had no experience that enabled you to do it, so it must be something that is coming out of your nature. Unless there’s angels around, anything you do is either a result of your internal nature or some impact of experience. And experience is extremely impoverished. It does not have much of an effect on what you are. It modifies it a little bit but, just like your physical growth: you couldn’t have eaten different food and had wings rather than arms.

The same is true of intellectual development. And the same is true in moral life. You’re constantly making choices and decisions and judgments. Sometimes you don’t know how to do it, but over a wide range, you know what’s right. And other people agree with you about what’s right. And even when you disagree with people, you find shared moral ground on which you can kind of work it out. That’s true on every issue.

Let’s take the war in the Gulf. You find someone who thought the war was terrific and overwhelmingly you find they share your moral grounds, they just are basing themselves on different judgments about the facts, or something like that. The same is true of slave-owning. You take a look at the debate over slavery; it was largely on shared moral ground. And some of the arguments were not so silly. You could understand the slave owner’s arguments. A slave owner says, “If you own property, you treat it better than if you rent property. So, I’m more humane than you are.” We can understand that argument. You have to figure out what’s wrong with it, but there is shared moral ground over a range that goes far beyond any experience. And this can only mean –again, short of angels– that it’s growing out of our nature. It means there must be principles which are embedded in our nature or are at the core of our understanding of what a decent human life is, what a proper form of society is, and so on and so forth.

Now, here we’re moving into speculation because no one has done the proper work, but if there is ever to be sort of a liberatory social understanding, it’s going to have to come from inquiry of this sort. That’s still in the future, but it’s something one could contemplate. That’s the way to proceed to gain some rational understanding of human beings. One of the few areas where we can do it successfully happens to be language. That’s why it’s interesting to study. It shows a lot about what humans are like.

AVA: This isn’t the mainstream approach to linguistics.

NC: Right, it’s a specialty. In fact, when I got into the field, this wasn’t linguistics at all.

AVA: What was it called –your area of research?

NC: It was called nothing. (Laughs) That’s why I’m teaching at MIT. I had no real backround, no professional training. I hadn’t been to college for years, I didn’t have any intention of staying in academic life –which I couldn’t stand. MIT was this scientific university that was willing to take a chance on something that looked intriguing. The professional linguists didn’t know what I was talking about. The first years in which I was working, I would publish in journals that were, you know, library science or engineering journals, not linguistics journals. I was never published in a linguistics journal. And then the field sort of took off, it became its own field. So now this is a field that we call linguistics, if you want, or you can call it something else, but by now it’s really developed enormously. Out of its own internal intelllectual challenges it just grew up. And the old linguistics basically disappeared because there was nothing to do in it.

AVA: Who has done the most interesting work on the physiological side of language development? What do we know about that?

NC: We know very little –as compared with, say, the physiology of vision– and there’s a very simple reason for that. The reason is that we allow ourselves to torture cats and monkeys –maybe it’s right or maybe it’s wrong, but we permit it. If you torture monkeys and cats, you can learn something about their visual systems. You stick electrodes into their striae cortex when they’re looking at something and you see what fires and what doesn’t fire. With intrusive experimentation –which is basically torture– you can learn a lot about an organism. You don’t do it to humans, but you figure human visual systems are pretty much like monkey visual systems, which is probably true, you can tell by autopsies.

But you can’t do this with language because there’s nothing like a language faculty in any other organism. So, you can’t torture cats and monkeys and find out anything about human language. Fortunately, we don’t have Nazi doctors, so the only types of experimentation that can be carried out on the brain are, basically, nature’s experiment: a guy gets hit in the head with a crowbar or somebody has a seizure. But that kind of evidence is just too unselective.

AVA: Can’t they figure out the sequence in which abilities are lost as different kinds of seizures onset, and eventually develop a map of the brain?

NC: You get very weak data. Pathological data is extremely poor, because the experiments aren’t controlled. In natural experiments too much goes wrong. If you want to do an experiment, you have to stick an electrode in a particular cell and determine what that cell is doing. But nature doesn’t do that. If you had a stroke, let’s say, some class of things goes wrong and we try to pick out what was relevant to language there. It’s very, very hard. The brain sciences can’t do much at this point. We don’t have methods of non-intrusive experimentation which would allow you to learn a great deal about human language. There’s some –you can learn things about electrical activity through experimentation that’s not intrusive, but it’s not selective enough to teach you much.

AVA: Do the computer scientists use your research? Or contribute to it?

NC: Computer sciences is a wide range of things. At one point I worked in automata theory. There was interest in developing a general mathematic theory of various kinds of symbolic systems in which language is one and computer languages are another. There’s work on complexity theory, which tries to talk about the complexity of algorithms: what kind of programs are harder to carry out and which one’s aren’t? We try to look at language applying some of what’s known about complexity theory. But those are pretty weak connections. The closest connection is just simulation. There are lots of complex processes where you can learn something by trying to simulate them. And languages are, at their roots, complex kinds of computational systems; so you can try to simulate some of the things by computers. If you have a model of speech perception, let’s say, you can try to simulate it and see if you can learn anything by how the simulation works.

AVA: Howard (a mutual friend) told me that your son writes software.

NC: At the moment. He finished a year of graduate math at MIT and decided it’s not for him, and he dropped out. Came out here.

AVA: I ‘d heard he’d written a symphony.

NC: (Blushes) When he was a kid –he was a good musician and in elementary school and junior high he took part in composition competitions and he wrote something in one of the classes… It wasn’t a symphony.

AVA: And one of your daughters is still working in Nicaragua?

NC: She’s working with Barricada Internacional. She had worked in desktop publishing up here and went down there and has been there about three years, I guess.

AVA: What exactly is Barricada International?

NC: It’s the international edition of Barricada, which was the Sandinista newspaper.

AVA: It’s not anymore?

NC: It’s not officially the Sandinista newspaper, but it’s still sort of related.

AVA: And what does she do?

NC: She has skills which, by the standards of a third world country, are pretty extensive. She does things –kind of troubleshooting, or teaching people how to do desktop publishing and the use of computers. Desktop publishing –that whole technology is very good in third-world countries. It sounds high-tech, but the fact is that it’s extremely cheap as compared to the standard printing, and it’s just the appropriate technology for people without resources.

AVA: Along what lines would you like to see this society reorganized? Do you ever think about a serious party forming in the U.S. that could gain power and change things?

NC: I think the United States desperately needs just ordinary reformist parties of the social democratic type. And the reason is, we’re unusual among the industrial societies in lacking elementary human services that are taken for granted in the civilized world. National health service. Just guaranteeing that people have health care, have a place to live, have something to eat. Nothing very fancy, just the things you would think that a civilized society would take for granted. Day care. Preventive medicine –not just dialysis but things that people need in their lives to prevent them from getting sick. We have to have an educational system that works. We have to have some way of keeping people in school instead of jail. We have by far the highest prison population per capita. What’s happening to the country is that it’s moving towards a third world-society with a sector of very wealthy and a vast sector of people that are just out of it. This is such a rich country that the proportions are different than say in Brazil; but the similarities are very striking. And that’s got to be retarded. In other state-capitalist societies there’s some kind of social contract that we don’t have. Like Germany where–I don’t think they’re very nice places, myself; in many ways this is a much freer and better society– but they do have that.

AVA: Why should we shoot for such a limited goal?

NC: That’s not shooting very far. That’s joining the civilized world.

AVA: Right.

NC: That’s a first step. Beyond that… in my view, the 18th century revolutions were aborted. I’m an old-fashioned conservative. I think the 18th century libertarian ideals were basically correct: there shouldn’t be concentrations of power. Power should be under popular control. The centers of power that people thought about in those days were the church, the feudal system and the absolutist state. And so they said, “Okay, let’s dissolve that.”

But in the 19th century a new center of power developed: corporate capitalism. Corporate capitalism destroyed liberalism. Liberal thought kind of broke on these rocks of rising corporate capitalism. A new center of control and concentration of power developed, out of public control. The same standard libertarian ideals that made you opposed to an absolutist state make you opposed to capitalism. And it’s always corporate capitalism, because it’s going to concentrate.

The mechanisms of production and distribution –the determination of what happens in the society has to be under public control. Now that can mean workers’ councils or community control of industry and financial institutions or whatever, but it’s got to be basically worker and community controlled. And unless that’s achieved, we will never have achieved the 18th century revoution.

That’s only part of it; there’s lots of other forms of authority and domination and oppression in the world. You look at relations between people of color and whites, men and women, parents and children –anywhere you go there’s forms of authority which have to justify themselves. Any form of authority requires justification; it’s not self-justified. And the justification can rarely be given. Sometimes you can give it. I think you can give an argument that you shouldn’t let a three-year-old run across the street. That’s a form of authority that’s justifiable. But there aren’t many of them, and usually the effort to give a justification fails. And when we try to face it, we find that the authority is illegitimate. And anytime you find a form of authority illegitimate, you ought to challenge it. It’s something that conflicts with human rights and human liberties. And that goes on forever. You overcome one thing and discover the next.

In my view, what a popular movement ought to be is just basically libertarian: concerned with forms of oppression, authority and domination, challenging them. Sometimes they’re justifiable under particular conditions, sometimes they’re not. If they are not, try to overcome them.

Now the major one in our society has to do with the fact that the country is owned by a small group of people. And that determines what is produced, what is distributed, what is consumed, what you see, what you read, where you work, whether you work, what happens in the political system. Virtually everything is traceable back to that centralization. And until that’s overcome –until the power in that system is diffused–there isn’t going to be any operative political freedom. There isn’t going to be any operative electoral freedom, and so on. But, that’s not the whole story. There’s plenty more.

After his talk, a woman had asked Chomsky, “Do you think we’re doomed as a species?”

He replied, “If the only value in human life is maximization of gain, if the only thing that drives people is greed, then you can bet your life that the civilization is not going to survive very long. If that’s all there is to human life, you can forget it, this is not a viable species. I don’t see any reason to believe that’s true, incidently. Those are really characteristics of modern capitalism. There are other forms of vicious, destructive social organization, but this is really the only one that has said that people are simply entities driven by greed and has turned that into a virtue.

“I don’t see any reason to believe that. People don’t act like that in small social groups. Like in a family: unless you’re pathological, you don’t try to steal food from your children because you’re hungry or simply because you have the power to take it.”

FAAAs

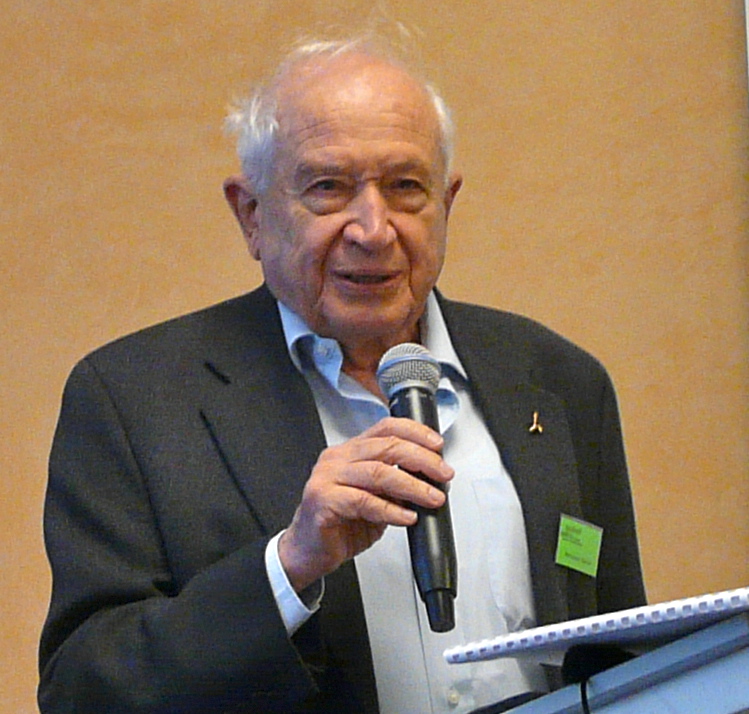

I couldn’t quite picture what Chomsky was saying about Homo Sapiens’ unique linguistic ability, until years later, when I heard Raphael Mechoulam discussing Fatty Acid Amino Acids (FAAAs) at a meeting of the International Cannabinoid Research Society. This is from my report in O’Shaughnessy’s:

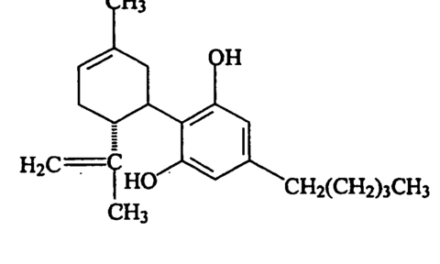

In the late 1980s, after the CB1 and CB2 receptors had been discovered, Mechoulam’s lab began searching for compounds in the body that would activate them. It was assumed that the receptors had not evolved to respond to plant cannabinoids. But the fact that THC and the other plant cannabinoids were lipophilic —preferring fatty molecules to water— convinced the investigators to narrow their search. The body’s own cannabinoid-receptor activators would almost certainly be lipids. “Nature is stingy,” Mechoulam generalizes. “If it knows how to do something, chances are it will do it again with small changes so it will not have to learn new things.”

William Devane and Lumir Hanus, fellows in Mechoulam’s lab, eventually isolated arachidonic ethanolamide (AEA), one of many derivatives of arachidonic acid, and named it “anandamide,” after the Sanskrit word for “supreme joy.” (Devane was studying Sankrit. Mechoulam had told him “There are many synonyms for ‘sorrow’ in Hebrew, but considerably fewer for ‘joy.’”)

A second endogenous cannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) was identified in 1994.

Mechoulam’s colleague Esther Shohami found that 2-AG levels went up nearly 10 times following closed head injury in mice. A follow-up experiment showed that mice given 2-AG after closed head injury suffered about half as much damaged tissue —proving that 2-AG exerts a neuroprotective effect. Shohami found Arachodonoyl Serine (AraS) had a similar neuroprotective effect, even though it doesn’t bind to the CB1 or CB2 receptor. Like 2-AG, AraS is a fatty acid bound to an amino acid.

“There may be hundreds of compounds formed by fatty acids binding to amino acids or their derivatives in the brain,” Mechoulam told the ICRS IN 2012. “Identifying them and understanding their function could shed light on the mechanisms of disease and give medical researchers powerful diagnostic tools.

“Why does the body spend so much energy synthesizing so many different compounds?” Mechoulam asked. “It doesn’t make sense. There should be something behind it.” Mechoulam said, “We should be able to diagnose a disease before we have the physical signals, which may be too late. We should be able to analyze and find out if something is going wrong. Is it possible… If we looked at the cluster of fatty acid amino acids maybe we would see that there is always a change in these compounds during a pathological situation. Maybe it is not a change in one compound, say 2-AG, but there is a change in many of the compounds. Maybe we should be looking at clusters of compounds as biomarkers –Not just one compound but 10 or 15 compounds.”

His hope is that changes in FAAA clusters will be detectable in blood. “Obviously one cannot look in the brain,” Mechoulam said. Fortunately, however, researchers led by Mauro Maccarrone of the University of Teramo have confirmed “that sometimes changes in the brain are paralleled by changes in blood cells.” This raises the practical possibility that the profiles of various FAAA clusters can be tracked and correlated with pathology, aging, mood change, etc.

“It is tempting,” Mechoulam wrote in the abstract of his ICRS presentation, “to assume that the huge possible variability of the levels and ratios of substances in such a cluster of compounds may allow an infinite number of individual differences —the raw substance which of course is sculpted by experience.”

He said he had asked a statistician if 200 compounds could yield eight billion distinct personalities. “The answer was ‘Of course.’”

He said he had asked a statistician if 200 compounds could yield eight billion distinct personalities. “The answer was ‘Of course.’”

I flashed on Chomsky: If some 200 FAAAs in the brain can shape aspects of personality, surely they can enable the understanding of language! Our “hard-wiring” for this unique ability may consist of 200 minuscule globules of fat!