From O’Shaughnessy’s Summer 2009

In 2006 Afghanistan produced 92% of the world’s illegal opium, with 13% of the population involved in the trade.

The International Council on Security and Development has developed a “Poppy for Medicine” project model for Afghanistan as a means of bringing illegal poppy cultivation under control in an immediate yet sustainable manner.

The key feature of the model is that village-cultivated poppy would be transformed into morphine tablets in the Afghan villages. The entire production process, from seed to medicine tablet, can thus be controlled by the village in collaboration with government and international actors, and all economic profits from medicine sales will remain in the village, allowing for economic diversification.

As internationally tradable commodities, village-made medicines would also benefit the Afghan government. Pilot projects are needed to enhance the controllability and economic effectiveness of this counter-narcotics initiative.

Failed Approaches

Forced eradication and poppy crop substitution strategies are failing to provide Afghan farmers with access to the resources and assets necessary to phase out illegal poppy cultivation.

“If these foreigners really care about the people of Afghanistan, then why do they destroy our crops? Why do they deprive us from the only source of our livelihood, without providing us with any alternative? Is this fair?” These questions were posed by a local leader of the Kama District, Nangarhar Province.

Poppy for Medicine is an alternative counter-narcotics strategy that involves licensing the controlled cultivation of the plant to produce essential poppy-based medicines such as morphine. Unlicensed poppy cultivation would remain a criminal activity.

Poppy for Medicine projects were established in Turkey in the 1970s with the support of the United States and the United Nations, as a means of breaking farmers’ ties with the international illegal heroin market without resorting to forced crop eradication. Within four years, this strategy brought the country’s illegal poppy crisis under control.

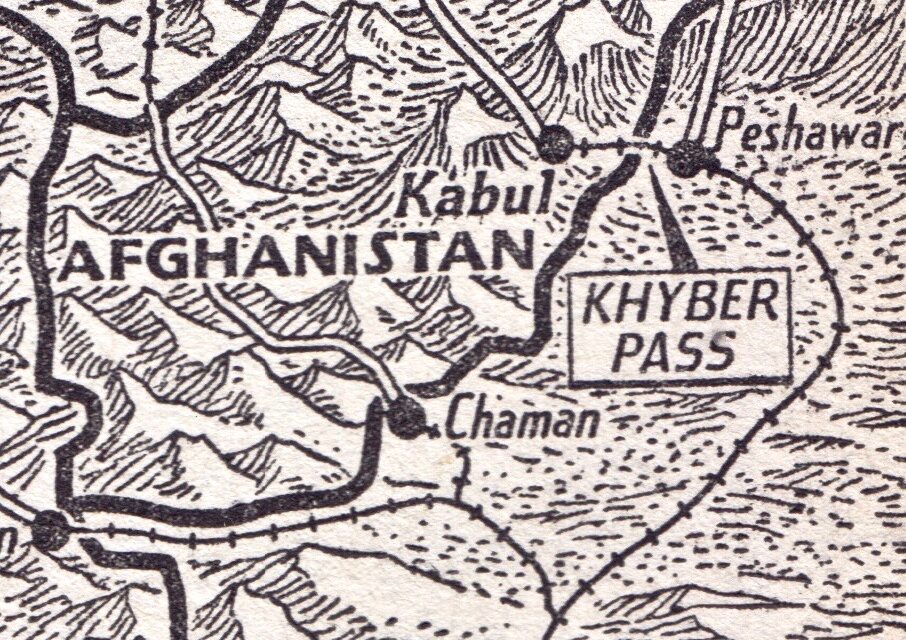

It would work as well in Afghanistan. With medicines being produced in the village, the villagers, together with government officials and international actors, can secure the entire manufacturing process, from the seeds to the final medicine tablets. The “export” of tablets from the villages to Kabul can also be completely secured.

The economic profits from Poppy for Medicine projects will remain in the village, providing the necessary leverage for farming communities to diversify their economic activities. The profits generated by exporting morphine tablets would accommodate all stakeholders, including middle-men and local power-holders. Producing internationally tradable commodities, Poppy for Medicine projects would also benefit the central government.

Given the increasing global demand for essential poppy-based pain medicines such as morphine, Afghanistan is ideally positioned to address the substantial gap in the international market for these medicines.

According to the International Narcotics Control Board, whose mandate is to ensure an adequate supply of morphine for medical and scientific purposes, 80 percent of the world’s population –including Afghanistan’s– face an acute shortage of essential morphine medicines.