From O’Shaughnessy’s cutting room floor (2018)

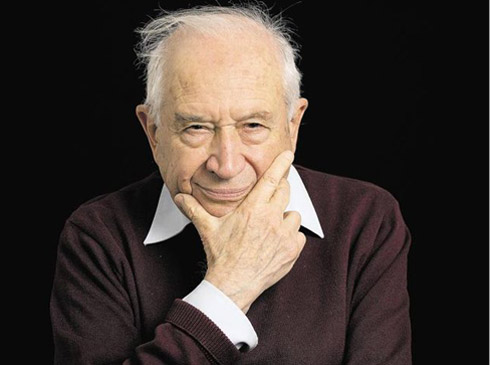

The Medical Board of California has been trying to revoke the license of William Eidelman, MD, an experienced Los Angeles cannabis clinician, who allegedly violated the standard of care when he issued an approval to a severely autistic boy whose father had sought the approval (and for whom cannabis would prove beneficial). The med board prevailed before an Administrative Law Judge in WHAT MONTH, 2018. Eidelman appealed the ruling in Superior Court and won a temporary stay of the revocation.

Eidelman is citing the so-called “immunity clause” in Proposition 215, the 1996 ballot measure by which California changed the Health & Safety Code to legalize the medical use of marijuana. Prop 215 included the following sentence: “Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no physician in this state shall be punished, or denied any right or privilege, for having recommended marijuana to a patient for medical purposes.”

Prop 215’s “immunity clause” was a line of Tod Mikuriya’s defense when he was prosecuted by the med board. ALJ Jonathan Lew ruled that the phrase “no physician… shall be punished” in Prop 215 conferred “conditional”as opposed to “absolute” immunity. Doctors still had to meet certain practice standards.

If absolute immunity is an absurdity, what does “conditional” immunity mean? Mikuriya asked, under what conditions do physicians who recommend cannabis need protection? All the complaints against him had come from law enforcement officers who resented Prop 215 passing —not one complaint from a patient or a caregiver. The costly, time-consuming investigation punished him —precisely what the drafters had foreseen and were trying to prevent.

CONFIRM WITH DALE AND BILL

The complaint against Eidelman came from Child Protective Services. The treatment had been beneficial to the five-year old patient. A school teacher who had demanded that he be medicated was so impressed by his improvement that she commented —according to the boy’s father— “At last a doctor got it right the first time.” The father was asked to bring the medication to school so that the nurse could administer it. Thinking it was legal, the father brought cannabis edibles to the school. The principal notified CPS that the parents were giving the boy marijuana. CPS deemed the parents unfit and filed a formal complaint against Eidelman, triggering a med board investigation.

Before his health ran out, Tod hired attorney Scot Candel to argue his case in Superior Court. Here is Candel’s commentary from O’Shaughnessy’s Winter 2007/08:

Appealing the Mikuriya v. MBC Ruling

By Scot Candel

The door to my office opened and a messenger dropped five boxes of files at my feet. I was taking over the case of representing Dr. Tod Mikuriya in his appeal against the Medical Board of California, and I had just been given all of the information on his case.

I carried the boxes one by one up to my office and started reading the charges against Dr. Mikuriya. The Medical Board was attempting to suspend Dr. Mikuriya’s license to practice medicine, claiming that he recommended marijuana to patients without doing a thorough medical examination to determine if the patients qualified for medical marijuana. It appeared that the government had subpoenaed all of his medical files and picked out 17 cases in which they argued Dr. Mikuriya recommended marijuana to an individual who was not qualified to use it.

I began reading the transcripts from the hearings. The first case involved a man who was bedridden with multiple sclerosis. It was undisputed that he was using marijuana to make his pain more bearable before he ever met Dr. Mikuriya. It was undisputed the marijuana was helping him. Dr. Mikuriya went to visit this man at his house to help him, and after examination and conversation with his caregiver, gave this man a recommendation to continue to use medical marijuana. There was no question this recommendation was justified. However, the medical board held that Dr. Mikuriya did not examine this man long enough to determine that medical marijuana would help him.

What? I had to read this twice. The patient was bedridden with multiple sclerosis, already using marijuana, which helped to ease his pain. There was no question that he had multiple sclerosis. There is no question that marijuana helped him. Yet they found that Dr. Mikuriya had not done enough to conclude that this person qualified to use medical marijuana. Wow!

I read on… A young woman was pregnant and having trouble gaining weight, which was jeopardizing the health of her unborn baby. Dr. Mikuriya examined her, reviewed her medical history, spoke with her and her mother, and then recommended that she use medical marijuana. The woman followed the recommendation, began gaining weight, carried the baby to term, and gave birth to a healthy baby. It was incredible. There could not be a better example of a successful recommendation of marijuana to a patient that truly needed it. The medical board again found that Dr. Mikuriya had not examined the patient thoroughly enough before recommending medical marijuana.

As I read on, each of these cases turned out to be a wonderful success story. Each patient was helped by the medical marijuana, and no patient ever complained. No patient abused the marijuana, and no patient ever sold the marijuana or shared it with any other individual. Every patient benefited from its use and no patient was harmed. These patients all could have been used as shining example of the benefits of medical marijuana. In every case, the medical board found against Dr. Mikuriya.

You don’t need to be a master chef to know when food is rotten, and you didn’t need to be a lawyer to realize the government had another agenda here. Dr. Mikuriya was a leading advocate for the legalization of medical marijuana, had testified as an expert witness in many trials about the benefits of medical marijuana, and had ruffled the feathers of many prosecutors and conservative politicians throughout California and across the country. This was a good old-fashioned witch-hunt.

We fought this case in Superior Court and prevailed on one key point. The medical board had charged Dr. Mikuriya with illegally prescribing marijuana to his patients. We convinced the judge that marijuana is not prescribed, it is recommended, and thus cannot possibly be prescribed illegally. Unfortunately, he rubber-stamped the administrative law judge’s other key findings.

Frustration and bewilderment don’t begin to describe our feelings as we left the courtroom wondering how much longer these ridiculous political games would continue. Dr. Mikuriya did not rule out an appeal. But in his final years there would be other demands on his time, energy, and funds.

The fact that the government tried so hard to prosecute Dr. Mikuriya is a testament to his importance to the medical marijuana movement.

Thank you, Dr. Mikuriya