Yes, Aaron Sorkin’s “Trial of the Chicago Seven” was a falsification of history. Yes, his exploitation and dissing of Dr. Joycelyn Elders on that West Wing episode was vile. Yes, his impassioned support for Sony execs Scott Rudin and Amy Pascal after their racist emails were exposed was shameless. But it was Christmas, the NBA games were over, and wasn’t Jesus all about forgiveness? So I hit play and “Being the Ricardos,” written and directed by the prolific Sork and underwritten by Amazon Studios, came streaming across the screen.

In Sorkin’s script, several crises that Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz dealt with during their marriage all come to a head in one week of September ’52. I prefer the literal truth, but I guess a screenwriter is entitled to compress the chronology.

Sorkin deftly provides relevant background with pseudo-documentary interviews of I Love Lucy’s executive producer, Jess Oppenheim, and two staff writers. They reminisce about the phenomenal popularity of their show. Nowadays a hit TV show attracts 10 to 15 million viewers. I Love Lucy drew 60 million in a USA with exactly half the population (156 million in ’52, 333 million in 2021.)

With tasty restraint, Sorkin splices in black-and-white footage from the TV show that shows how well his movie was cast. The Spanish actor Jason Bardem turns into the Cuban-born bandleader Desi Arnaz, right down to “Babalu” on his bongos. Nicole Kidman’s Lucille Ball is brilliant, brave, subversive, and self-confident —but vulnerable on the love front. If she doesn’t get the Oscar for best actress, I say “Stop the Steal!”

Two disasters hit the happy couple on Sunday night of the Sorkinized week. Confidential Magazine has rolled off the presses with a graphic article about Desi’s extra-marital sex life. Lucy, hurt and angry, confronts him. Desi says the story is a scandal-sheet fabrication, Lucy accepts his denial, and their furious fight turns into a forgiving fuck. But while the Arnazes are getting it on, the voice of Walter Winchell —America’s most influential gossip columnist— comes over the radio proclaiming that “the top television comedienne” has been identified to the House Un-American Activities Committee as a Communist. Coitus interruptus abruptus cuts to to CBS studios on Monday morning as the writers and actors discuss the script of the upcoming I Love Lucy episode.

The episode calls for Lucy to promote reconciliation between Fred and Ethel Mertz, the Ricardos’ neighbors, who have been feuding. Sorkin provides realistic glimpses of the production process. (A much funnier bunch of writers pitch jokes to one another in “My Favorite Year” starring Peter O’Toole as guest star on the Sid Caesar show, which, BTW, also pulled in 60 million viewers.) Lucille Ball dislikes the director, tells him he doesn’t understand that her specialty is “physical comedy.” She questions the logic of the script and the blocking of the action.

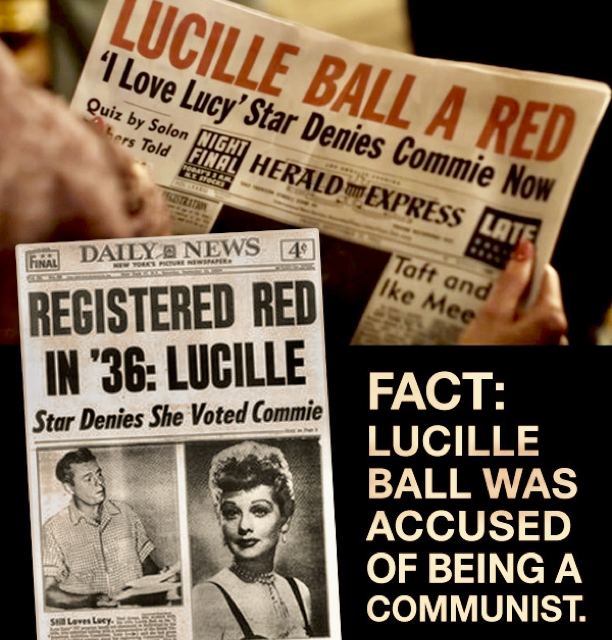

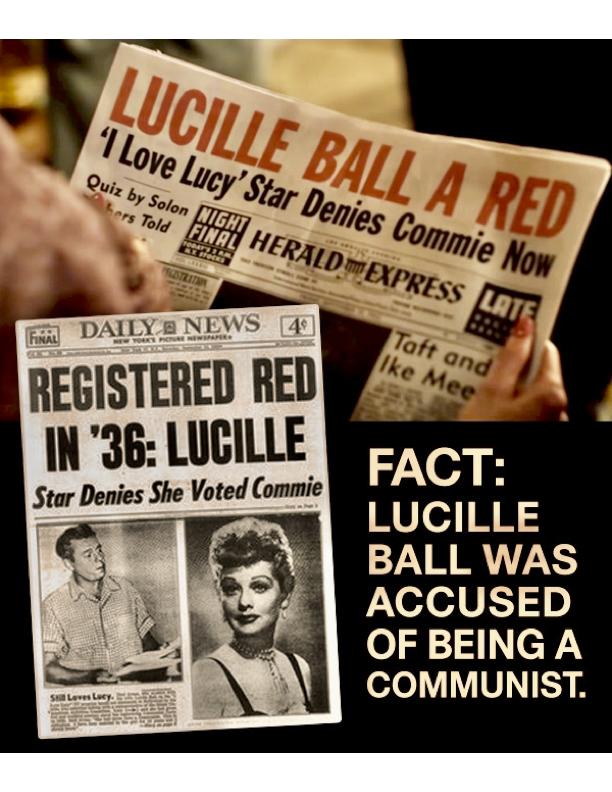

Lucy and Desi have a tense meeting with executives and lawyers from CBS and the corporate sponsors. Desi tells the assembled White Men in Suits that Lucy has already been grilled by the House Un-American Activities Committee and cleared. He doesn’t want Lucy explaining that she really did register as a Communist in the 1936 election, out of respect for her beloved grandfather, a well-intentioned “friend of the working man” who helped raise her after her father died when she was only four. Sorkin cops a great line from Lucy’s actual HUAC testimony about registering Communist in 1936: “It was almost as terrible to be a Republican in those days.”

Desi assures the corporados that Lucy had inadvertently “checked the wrong box” when she registered in ’36. She is insulted and resents his dishonesty.

As days go by with no more red-baiting in the media, there’s hope that the threat will blow over. Lucy summons Ethel and Fred to a secret 2 a.m. rehearsal at which she changes the staging of a crucial scene. We see Ricky leading his orchestra at Ciro’s, a Los Angeles nightclub. There is a flashback to the mid-1940s, when Lucy, after a decade of playing in B-movies, got her only starring role in a feature film, the kind of part usually reserved for “serious” actresses like Bette Davis, Katherine Hepburn, and Rita Hayworth. When the studio doesn’t renew her contract she turns to radio and makes a hit of a show created by Jess Oppenheim called “My Favorite Husband.” Her radio husband, a gringo, is in mid-level management. CBS execs see studio audiences responding to Lucy’s expressive humor and offer her a TV version of My Favorite Husband. She insists that the male lead be her real-life husband, a flamboyant band leader. This leads to another crisis as the execs deem Lucy’s marriage to Desi, who was born in Cuba, inappropriate as the basis for a sitcom.

In Sorkin’s scenario, there is a meeting at which Lucy forces the racist corporados to back down. In real life she and Desi had to organize a nationwide tour of a vaudeville show in which they performed together to prove, by selling out theaters everywhere, that US Americans were not offended by their marriage. Finally, in the fall of 1951, CBS aired “I Love Lucy,” sponsored by Philip Morris.

In “Being the Ricardos” and in real life the Los Angeles Herald-Tribune ran a huge above-the-banner headline in red ink, “Lucille Ball a Red,” on Friday, just before the cast is about to perform the new episode before a studio audience. The moment of truth is at hand. It might be curtains for I Love Lucy, despite its phenomenal ratings.

But a Sorkinized Desi Arnaz has been maneuvering behind the scenes and arranged a response to the red-baiting that takes everyone, including Lucy, by surprise. Addressing the studio audience before the show begins, Desi puts through a phone call to an unseen man with an authoritative voice who proclaims that Lucille Ball has been thoroughly investigated and “one -hundred percent cleared” of any Communist taint. Desi asks the man to identify himself. The voice says “This is J. Edgar Hoover.” The audience erupts in joyous applause as love of Lucy and love of country merge in their hearts and minds. Everyone involved with the show is deliriously happy that their employment will continue. As the movie ends, the only unhappy character is Lucille Ball, who has just found another woman’s lipstick on her husband’s handkerchief.

I should have seen J. Edgar Hoover coming, but I didn’t. Ever since FBI director James Comey began investigating Donald Trump’s ties to Russia five years ago, liberals of Sorkin’s stripe have been glorifying the Bureau (and the CIA, for good measure). But it took the Sork himself to make J. Edgar Hoover —racist, anti-labor, war-mongering, blackmailing, cross-dressing, power-mad J. Edgar Hoover— the Deus Ex Machina who keeps Lucille Ball off the blacklist!

It was Christmas and I intended to be forgiving. I went online to see if there might, in this instance, be some factual basis to Sorkin’s glorification of Hoover. Did he actually acknowledge that Lucille Ball was a loyal American?

No way. As the intrepid muckrakers Jack Anderson and Dale Van Atta reported in the Washington Post in 1989, “The committee (HUAC) forgave her, but J. Edgar Hoover never forgot. The FBI director continued to collect evidence about Ball, even though the FBI claims that it never officially investigated her. Our associate Scott Sleek obtained the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s secret file on Ball and her first husband, Desi Arnaz. The file contains memos stamped ‘confidential’ and addressed to Hoover. Many of the memos begin with ‘pursuant to your request,’ indicating that Hoover cared enough to keep personal tabs on Ball. Large portions of the FBI memos are blacked out because the FBI still considers them not ready for prime time. Here are some of the tidbits that FBI agents passed on to Hoover:

“The Daily Worker, a communist newspaper, alleged in 1951 that Ball was among the stars who had once been vocal in their opposition to McCarthy but then later kept their mouths shut. In February 1946, Arnaz appeared in a show sponsored by the Hollywood Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions, a group the FBI said was a communist front. A Hollywood writer said that in 1937 she attended a Communist Party membership meeting at Ball’s house. The writer said Ball was not there but had approved of the meeting. Hoover kept a clipping of an Associated Press story about Arnaz’s arrest in 1959 for public drunkeness. Why would the FBI director be interested in Arnaz’s police record? Hoover was notorious for collecting ammunition against his enemies to use for future face-offs, and a face-off with Arnaz was a distinct possibility. Arnaz headed Desilu Productions, which produced the TV show ‘The Untouchables.’ We have already revealed that Hoover despised the series because it credited Treasury agent Eliot Ness for feats achieved by the FBI. Hoover had his G-men monitor the show for mistakes.”