In the summer of 1967, Fred Gardner arrived in San Francisco with the Vietnam War weighing heavily on his mind. Gardner was 25 years old, a Harvard graduate and a freelance journalist for a number of major publications. He was attracted to Northern California’s mix of counterculture and radical politics, and hoped to become more actively involved in the movement to end the war. He was particularly interested in the revolutionary potential of American servicemen and couldn’t understand why antiwar activists and organizers weren’t paying more attention to such a powerful group of potential allies.

• I arrived in the Bay Area because my wife had a fellowship to Stanford and I thought —like a jackass— that her getting a master’s in math was as important as my fabulous job on the editorial board of Scientific American. My friends and family were Back East and I was not especially attracted to Northern California (until I saw the redwoods in Cazadero). I knew damn well what was keeping the peace movement from seeing GIs as potential allies: The Class Thing.

Ever since completing a two-year stint in the Army Reserves in 1965,

• The National Guard/USAR stint was six years. I enlisted in ’63 and was honorably discharged in ’69, having made pfc. The circumstances of my enlistment are described here.

Gardner had been closely watching the increasing instances of military insubordination, resistance and outright refusal that were accompanying the war’s escalation. From the case of the Fort Hood Three — G.I.s arrested in 1966 for publicly declaring their opposition to the war and refusal to deploy — to the case of Howard Levy, an Army dermatologist who refused his assignment to provide medical training for Special Forces troops headed to Vietnam, it was clear that the Army was fast becoming the central site of an unprecedented uprising.

The February 1966 issue of Ramparts, in which Master Sergeant Don Duncan, the most decorated enlisted man in the Army, declared “I Quit!” made a big impact on me and everybody else who saw Duncan on the cover of the magazine, in uniform and arms crossed and determined.

Soon thereafter I interviewed Captain Sanford Wolfson, MD, who had been a surgeon at Bien Hoa, and was court-martialed after telling General William C. Westmoreland —during an inspection— that the hospital was ill-equipped to cope with the number civilian casualties they were getting. Wolfson recalled, “Westmoreland was shocked that anybody would confront him with the truth about the medical situation. It was the kind of inspection where everybody’s at attention and says, ‘Yes sir, everything’s fine, sir.’ As he was leaving the ward, the hospital commender tried to deny what I had told him. Westmoreland said, ‘Don’t you worry, Colonel, I can tell a psychotic just by looking at him.” The charge against Wolfson would be refusal to obey a direct order… to shave his goatee.

The court-marital of Dr. Howard Levy was reported on by Andrew Kopkind in the New York Review of Books, altering the mood of the intelligentsia. Levy said the Green Berets’ ulterior purpose in learning the healing arts was to gather intelligence that would endanger the people they were supposedly helping. For refusing to train them he did three years in Leavenworth. Donna Mickleson and I chose to open the UFO in Columbia, SC —the town frequented by soldiers from Fort Jackson— because there were some GIs stationed there who had attended Levy’s court-martial and we figured they’d find us. We were following Howard Levy, literally and figuratively.

The Reserve unit I was assigned to was headquartered on post. There was a big photo of Senator Strom Thurmond as you entered the armory where we drilled on week-ends, and there was a red-headed officer named Harry Dent who briefed the troops on current events. Historians credit Dent with developing the Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy.” I was assigned to permanent KP, which I considered good duty: meaningful work, companionship, access to food, no boredom.

By 1967, the “G.I. movement” was capturing national headlines.

It was February ’68 when the media took notice of anti-war sentiment in the ranks. Jack Newfield and Paul Cowan of the Village Voice covered the “pray-in for peace” conducted by 21 GIs in uniform at a Fort Jackson chapel. Then Ben Franklin of the NY Times broke the story where the decision-making elites would read it.

And it wasn’t just the war that was aggravating American servicemen. The military’s pervasive racial discrimination — unequal opportunities for promotion, unfair housing practices, persistent harassment and abuse — fueled increasing outrage among black G.I.s as the war progressed. Influenced by the civil rights and black liberation movements, black soldiers participated in widespread and diverse acts of resistance throughout the Vietnam era. Racial tensions were particularly high in the Army, where a vast majority of draftees were being sent, and where evasion, desertion and insubordination rates among black G.I.s exploded in the war’s later years. An antiwar movement in the military was beginning to take shape, with black soldiers often its vanguard.

As Gardner sat in the radical coffeehouses of San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood that summer, he thought about the explosive power of servicemen turning against the war and wondered how that power could be supported and nurtured by the civilian antiwar movement.

I had been living in Noe Valley, trying to save a doomed marriage. On those rare occasions when I had a cup of coffee at the Cafe Trieste, I was probably reading Herb Caen or the Sporting Green.

Most of all, he wanted to find a way to reach out to disaffected young G.I.s, to show them that there was a whole community of antiwar activists and organizers who were on their side. He finally settled on an idea: opening a network of youth-culture-oriented coffeehouses, just like the ones in North Beach, in towns outside military bases around the country.

The model that I thought could be re-created in Army towns was a political cabaret on Broadway called The Committee. The director, Alan Myerson, provided an extremely useful piece of advice before I left town: put a rheostat near the cash register so whoever’s handling the register can also control the stage lights.

In January 1968 he did just that, traveling with a fellow activist, Donna Mickleson, to Columbia, S.C., home of Fort Jackson, one of the Army’s largest training bases and the crown jewel of the state’s many military installations.

Donna and I hit Columbia in September, ’67. On our first day in town we went to a real estate agent to rent a house. I said I was setting up a new business in town, my wife and kids would soon be joining us. Donna said she was my sister-in-law and we wanted a big place. The realtor said she had two houses that met our needs, one on York, one on Waccamah. They both sounded good. We went to check out the place on York first, and it was perfect —four bedrooms, not too far from Main St., and bordering on some piney woods (the grounds of an insane asylum). When we got back to the office we told the realtor we liked it. She said, “That’s good, because the house on Waccamah, well, Mrs. Westmoreland is a little reluctant to rent it out to a family with young children. It’s the house where the general grew up, and she thinks it’s going to be a national shrine someday, after he becomes president.”

Donna and I were all “Mm-hmm, how interesting.”

“Would you like to go see it?”

We looked at each other and one of us said, “Thanks anyway.” We signed the lease for the house on York. Back to Parsons in the New York Times:

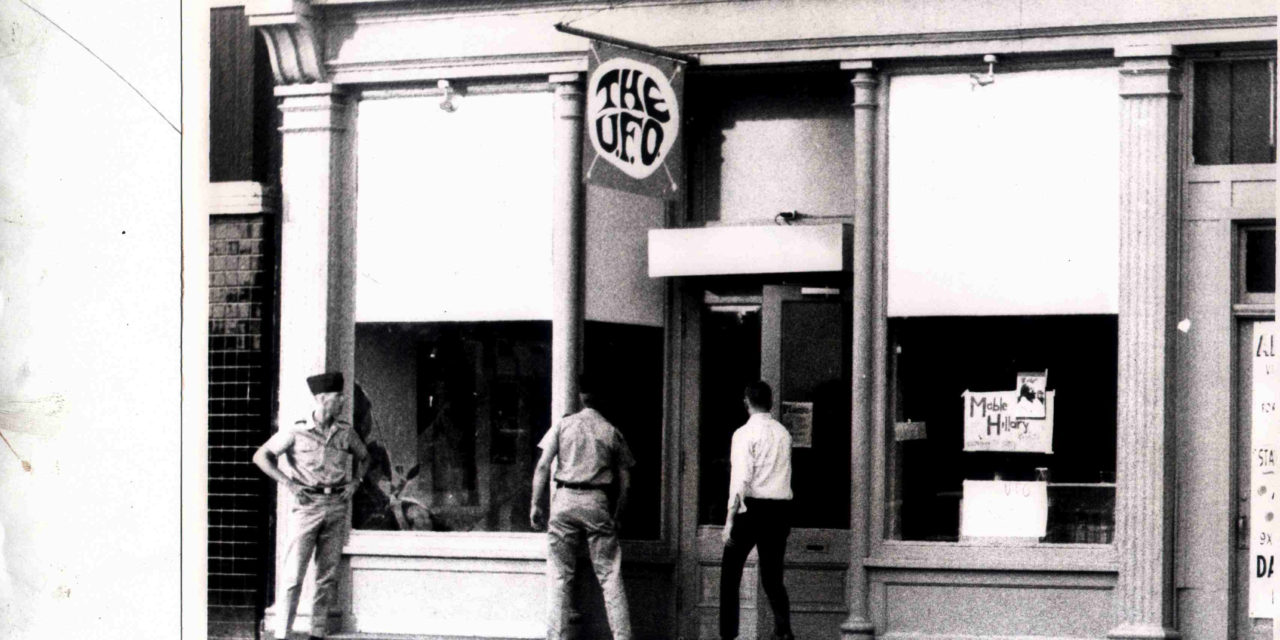

The UFO coffeehouse, decorated with rock ’n’ roll posters donated from the San Francisco promoter Bill Graham, quickly became a popular hangout for G.I.s — and a target of significant hostility from military officials, city authorities and outraged local citizens (“It’s a sore spot in our craw,” a Columbia official said.) The coffeehouse was located just off base, out of the military’s reach but close enough for soldiers to visit during their free time — places where active-duty servicemen, veterans and civilian activists could meet to plan demonstrations, publish underground newspapers and work to build the nascent peace movement within the military.

By the summer of 1968, major antiwar organizations took notice of the controversy the UFO was stirring up in Columbia and initiated a “Summer of Support” to organize funds for more coffeehouse projects around the country. In ensuing years, more than 25 “G.I. coffeehouses” opened up near military bases in the United States and at a number of bases overseas.

Over the course of six years, the coffeehouse network would play a central role in some of the G.I. movement’s most significant actions. At the Oleo Strut coffeehouse in Killeen, Tex., local staff and G.I.s mobilized to support the Fort Hood 43 — a large group of black soldiers who were arrested at a meeting to discuss their refusal to deploy for riot control duty at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. A black veteran present at the meeting described its mood: “A lot of black G.I.s knew what the thing was going to be about and they weren’t going to go and fight their own people.” Army authorities were caught off guard by the publicity the coffeehouse brought to the case, and began to examine their strategies for dealing with political expression among the ranks.

When eight black G.I.s, each of them leaders of the group G.I.s United Against the War in Vietnam, were arrested in 1969 for holding an illegal demonstration at Fort Jackson, the UFO coffeehouse served as a local operations center, drumming up funds for lawyers and promoting the “Fort Jackson Eight” story to the national media. After G.I. and civilian activists created intense public pressure, officials quietly dropped all charges, signaling a shift in how the military would respond to soldiers expressing dissent.

Not all of the GIs United group were black. One of the white guys, Bruce Patterson, worked for many years in Mendocino County and wrote for the Anderson Valley Advertiser. I always appreciated his stuff and am sorry our paths never crossed. Maybe next year in Pendleton… One of the Fort Hood Three, David Samas, became a first-rate upholsterer in Fort Bragg and I’m glad we brought the red couch to him.

During its brief lifetime, the G.I. coffeehouse network was subjected to attacks from all sides — investigated by the F.B.I. and congressional committees, infiltrated by law enforcement, harassed by military authorities and, in a number of startling cases, terrorized by local vigilantes. In 1970, at the Fort Dix coffeehouse project in Wrightstown, N.J., G.I.s and civilians were celebrating Valentine’s Day when a live grenade flew in through an open door; it exploded, seriously injuring two Fort Dix soldiers and a civilian. Another popular coffeehouse, the Covered Wagon in Mountain Home, Idaho (near a major Air Force base), was a frequent target of harassment by outraged locals, who finally burned it to the ground.

Though their numbers dwindled as the war drew to a close in the mid-1970s, G.I. coffeehouses left an indelible mark on the Vietnam era. While popular mythology often places the antiwar movement at odds with American troops, the history of G.I. coffeehouses, and the G.I. movement of which they were a part, paints a very different picture. Over the course of the war, thousands of military service members from every branch — active-duty G.I.s, veterans, nurses and even officers — expressed their opposition to American policy in Vietnam. They joined forces with civilian antiwar organizations that, particularly after 1968, focused significant energy and resources on developing social and political bonds with American service members. Hoping to build the resistance that was already taking shape in the Army, activists at G.I. coffeehouses worked directly with service members on hundreds of political projects and demonstrations, despite relentless government surveillance, infiltration and harassment.

The unprecedented eruption of resistance and activism by American troops is critical to understanding the history of the Vietnam War. The G.I. movement and related phenomenon created a significant crisis for the American military, which feared exactly the kind of alliance between civilians and soldiers that Fred Gardner had in mind when he opened the first G.I. coffeehouse in 1968. Despite the extraordinary political and cultural impact that dissenting soldiers made throughout the Vietnam era, their voices have been nearly erased from history, replaced by a stereotypical image of loyal, patriotic soldiers antagonized and spat upon by ungrateful antiwar activists. In the decades since the war’s end, countless Hollywood movies, books, political speeches and celebrated documentaries have repeated this image, obscuring the war’s deep unpopularity among the ranks and the countless ways that American troops expressed their opposition.

This historical erasure serves a distinct purpose, casting dissent — from wearing an antiwar T-shirt to kneeling during the national anthem — as inherently disrespectful, even abusive, to American soldiers. A fuller reckoning with the era’s history would begin by acknowledging the countless G.I.s and civilians who stood together against the war. G.I. coffeehouses are a vital window onto this history, showing us places where men and women came together to share their common revulsion at the war in Vietnam, and to begin organizing a collective effort to make it stop.