By Fred Gardner May 27, 2019

Although it’s entitled “How Legalization Changed Humboldt County Marijuana,” Emily Witt’s article in the current New Yorker is not about new plant varieties but about new social realities. She opens with an assertion sure to please her recent hosts (whose hope is that a Humboldt appellation can ward off an Appalachian economy):

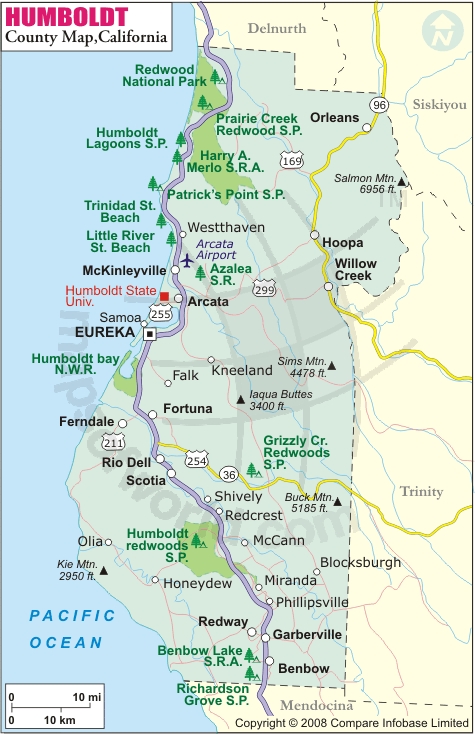

“For more than 40 years, the epicenter of cannabis farming in the United States was a region of northwestern California called the Emerald Triangle, at the intersection of Humboldt, Mendocino, and Trinity Counties. Of these, Humboldt County is the most famous.”

Says who? Did the McGarrigle Sisters ever sing about Humboldt? Did Doug Sahm? I think Mendocino is more famous.

“It was here, in hills surrounding a small town called Garberville, that hippies landed in the 1960s, after fleeing the squalor of Berkeley and Haight-Ashbury.”

The new settlers at the end of the ’60s included veterans seeking peace and sanity after Vietnam.

“They learned the practice known as sinsemilla, in which female cannabis plants are isolated from the pollen of their male counterparts, which causes the females to produce high levels of THC.”

Sin semillas in Spanish means “without seeds.” Gringos turned it into a one-word noun meaning not the growers’ practice of isolating female plants but the flowers put out by the sexually frustrated females, swollen and laden with resin, desperate to catch a grain of pollen. And it’s not just THC production that gets enhanced when un-pollinated female flowers are forced to keep putting out; levels of all their cannabinoids, terpenoids, flavonoids and other components get elevated.

Please forgive my Adrian Monk-like compulsion to straighten out minor factual errors. It’s not easy to fly into an unfamiliar scene for a brief visit, as Witt did in February, and grasp the whole complicated story. Pot partisans in Humboldt appreciate her effort. Kym Kemp says the NYer piece “takes a serious, long look at the local culture” and “is well worth the read as a summary of what occurred here over the last 50 years.”

Diane Dickinson, MD, says, “I thought the article was well done. I see lots of pain. Folks losing their properties due to huge fines. It’s a costly process to fit into and many are giving up. Lots of businesses are closing. Every business feels the struggle. And most wonder what the county is doing with all the fines they are collecting. I do have one patient I can verify that is paying off huge fines based on satellite photos from years ago of his greenhouse. It was more costly to fight it in court than to make monthly payments of $1,500 fines for years.”

An important source for Witt is Jason Gellman, 39, a second-generation grower. His parents, she writes,

“were hippies who moved to Humboldt County when he was two years old, in the early ’80s. They eventually managed to buy their own property… At that time, ten pounds of marijuana—the amount produced by eight or ten plants in a harvest cycle—could be sold for as much as $40,000, enough to support a family that grew most of its own food…

“Humboldt County’s first generation of cannabis growers used the crop as one of several sources of income. The second generation ‘worked hard, but it was different,’ Gellman said. ‘It was more growing weed for money,’ as a career. Gellman grew his first patch of cannabis at 14.”

North Coast sinsemilla was still commanding $4,000/lb when California voters passed Proposition 215 in 1996, legalizing marijuana for medical use. The prime mover, Dennis Peron, vowed to bring the price down to $3,200/lb. Some far-sighted growers hated him for that.

For more than a decade, Prop 215 was good for the small growers. Though dispensary operators kept paying less and less for flowers, demand increased as more Californians got doctors’ approval letters. Many growers took pride in providing the herb to people who benefitted from it. Witt writes, accurately:

“The medical-marijuana movement, which had been building for years, was led by AIDS activists, who wanted the right to use marijuana to treat symptoms of the disease.”

But she continues, misleadingly:

“In Humboldt, the bill was received quietly—activism tended to attract the attention of law enforcement—but the growers soon adapted to the new legal paradigm, posting their medical marijuana cards on their fences as cover.”

There was no bill to be “received” in Humboldt. Bills are enacted by the legislature. California’s medical marijuana law was enacted by us, the people. Drafted by pot partisans meeting at the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club, Prop 215 passed in November ’96 by a 56-44 margin. Activists from Humboldt had worked for the Yes-on-215 campaign —Eric Heimstadt and JJ Baker are two I recall— and it carried the county with 57% of the vote.

Here’s another misstatement of fact:

“At first, because federal law still banned marijuana, most people feared the consequences of growing more than 99 plants, the limit set by Proposition 215.”

Prop 215 did not set any limits on how much marijuana a patient could use or a “caregiver” could provide. Under the federal Controlled Substances Act, growers with more than 99 plants face a mandatory minimum sentence of five years.

Prop 215 allowed doctors to approve patients’ use of marijuana in treating any condition for which it provides relief. It also protected patients’ caregivers. Doctors would typically issue a letter confirming their diagnosis and patients would give growers copies of the approval letters to show to law enforcers in the event of a raid.

There was no such thing as a California “medical marijuana card” until 2004, when Senate Bill 420 kicked in. SB-420 stated: “Qualified patients, persons with valid identification cards, and [their] designated primary caregivers… who associate within the State of California in order collectively or cooperatively to cultivate cannabis for medicinal purposes, shall not solely on the basis of that fact be subject to state criminal sanctions.”

There were two big loopholes to SB-420, according to an analysis by attorneys Omar Figueroa and Lauren Mendelsohn:

“First, there was no limitation on how many patients or caregivers could join a collective, which eventually led to numerous collectives with thousands of members. Second, there was no limitation on how many collectives a patient or caregiver could join, which led to the same result. Over the years, this morphed into the ‘collective / co-op model’ where practically anyone with a medical cannabis recommendation could sign up to be a member of a medical cannabis collective and would then provide medical cannabis in exchange for ‘reimbursement’ for expenses, ostensibly on a not-for-profit basis.”

“Under this model, with no regulation whatsoever from state authorities, and minimal, if any, regulation at the local level, the medical cannabis industry in California grew, multiplied, and thrived.”

Witt in the New Yorker describes the dark side of this thriving industry:

“Newcomers arrived, from the East Coast, from Texas; there was an influx of immigrants from Bulgaria. Cannabis farmers started growing as much marijuana as they wanted. They diverted water from the rivers to irrigate their crops. They dumped pesticides into the watershed. They grew plants in national forests and state parks. They flattened mountaintops. The profits were high, and the risks were low—a grower who ran a big farm for two years could make out with two million dollars and then abandon the property, leaving the land a wreck.

The corporate media perpetrated the image of medical marijuana as some kind of scam. TV news channels ran exposé footage of seemingly able-bodied young men leaving dispensaries with brown paper bags. The Medical Board of California, which had put Dr. Mikuriya on probation for inadequate record keeping, allowed the proliferation of fast-buck potdocs who issued approval letters on the basis of three-minute exams. It almost seemed as if the media, politicians, and Deep State bureaucrats were intentionally discrediting the medical marijuana movement. The media to this day ignore the existence of the Society of Cannabis Clinicians —the serious specialists whose findings and observations will undoubtedly, in the years ahead, be replicated in clinical trials and published in “The Literature.”

In 2015, Witt writes, “California passed the Medical Marijuana Regulation and Safety Act, in an attempt to better control the trade.” (The acronym was MMRSA and the politicians called it “mersa,” which showed that no doctors had been involved in drafting or reviewing it, because “Mersa” is what medical people call Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a deadly pathogen. The politicians substituted Cannabis for Marijuana in the name of the Act and started calling it “MacCursor.”

Mendelsohn and Figueroa explain a key purpose of the Act:

“In order to force medical cannabis operators into the regulated system, an expiration date was put on collectives and cooperatives (with a floating date of one year after the state started issuing state medical cannabis licenses).”

The Act, the lawyers note, would soon be incorporated into something called “MowCursor:”

“After Proposition 64, known as the Adult Use of Marijuana Act (AUMA) passed resoundingly in late 2016 and established a similar, but different regulatory framework, regulators realized that they did not want to come up with two confusing sets of convoluted regulations, one for medical cannabis and one for adult-use cannabis. The Legislature ended up repealing the medical framework, and combining the two different regulatory frameworks into one unitary regulatory framework branded the Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MAUCRSA) which is currently in effect. Despite all of these changes, the sunset clause on collectives and cooperatives remained.”

AUMA imposed a 15% excise tax on all cannabis purchases. The underlying assumption is that marijuana is not really a medicine. No medicine is taxed at 15%.

Dr. Dickinson reports that her practice is down more than 80% since legalization kicked in. Her new patients are senior citizens seeking education and people growing more than six plants to meet their medical needs. Dickinson advises them to keep a notebook with their recipes to justify the size of their gardens.