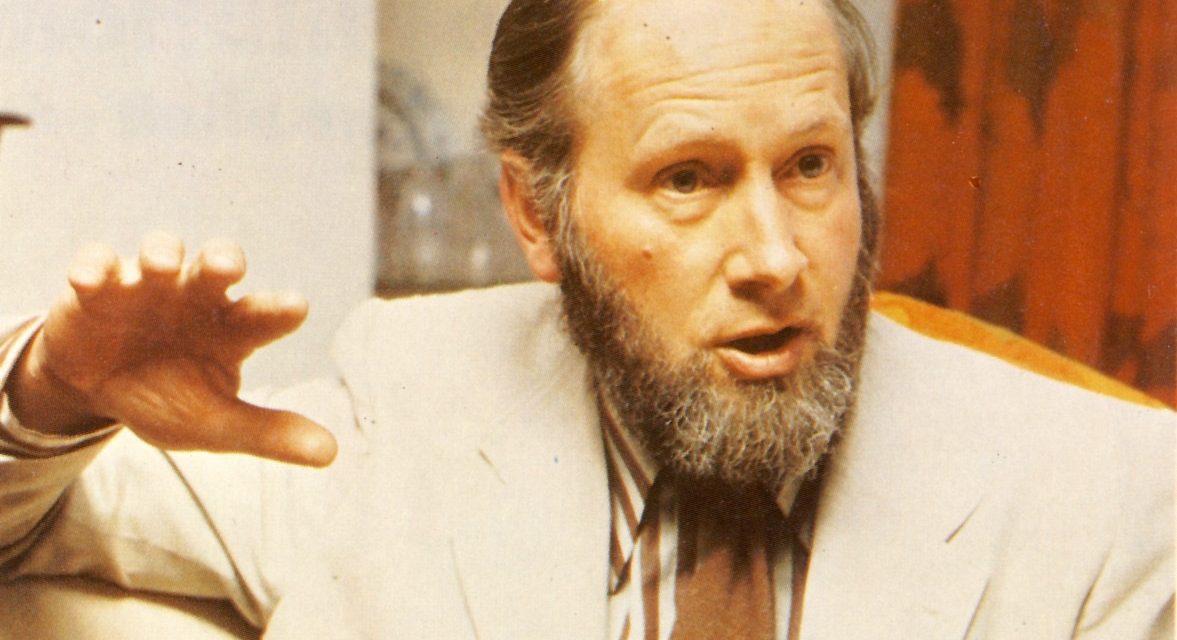

Alan Julian Macbeth Tudor Hart (b 1927) died from ischaemic colitis with secondary bowel perforation on 1 July 2018. Here is the BMJ obit By Penny Warren:

In 1971 a GP from a Welsh mining village submitted a paper to the Lancet. More than 45 years later doctors, researchers, and politicians still quote Julian Tudor Hart’s “inverse care law.”1

It states: “The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served. This inverse care law operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces, and less so where such exposure is reduced.”

It’s fitting that Tudor Hart, a fierce critic of market forces in medicine, should die aged 91 on the 70th anniversary of the NHS, which he defended so passionately.

Radical beginnings

Tudor Hart was born in London in 1927 into a communist medical family. He once described home as something of a “transit camp for antifascist refugees” and said that his father gave him works of Marx to read at school.

In 1940, aged 13, he and his sisters took refuge in Canada from the second world war with their grandfather, the artist Percyval Tudor-Hart. From this time he became an enthusiastic naturalist. On returning to London in 1945 he did his national service, but a spinal anomaly meant that he was discharged early in 1946.

Tudor Hart found his vocation in medicine and politics, describing the NHS as “a major experiment in democratic socialism.” He studied first at Queens’ College, Cambridge, in 1947 and then at St George’s Hospital in London, where he qualified in 1952. He worked as a GP in Notting Hill for five years and by this time had three children: Adam, Alison, and Penny.

In 1958 he took a paediatrics post at the Royal Hammersmith Hospital, and he then worked as a registrar for Richard Doll at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He was interested in epidemiological research, and its principles underpinned all of his later work. In 1960 he moved to Cardiff to work for Archie Cochrane at the Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit.

Tudor Hart’s first marriage had ended, but in March 1961 he met Mary Thomas, whom he married in 1963. Theirs was a very successful partnership, both personally and professionally, and Mary was vital to his projects and writings. They had three children: Robin, and twins Ben and Rachel.

The Glyncorrwg years

In 1961 Tudor Hart bought a rundown general practice in Glyncorrwg, a coal mining community in the Afan Valley. Although he later went into partnership with Brian Gibbons (who became the Welsh health minister), he was on his own to begin with, commenting later, “Initially, conditions were pretty squalid.”

He was keen to get a holistic picture of his patients’ health. The methods he had learnt from Doll and Cochrane helped, and Glyncorrwg became the Medical Research Council’s first research practice. From 1964 to 1985 Tudor Hart audited 500 deaths, which he described in a paper for The BMJ.2

He became the first GP in the UK to routinely measure blood pressure. He measured it in everyone in Glyncorrwg down to the last inhabitant—who turned out to have the highest reading—and he wrote it up in what would be the last single authored paper on blood pressure for the Lancet in 1970.3

Local cooperation was essential, and working in partnership with patients was a guiding principle for Tudor Hart. He formed a health committee in Glyncorrwg in 1975, which met monthly and discussed public health issues such as smoking.

The preventive health strategy paid off. In 1991 The BMJ published a study that found death rates in Glyncorrwg to be 30% lower than in the neighbouring village, Blaengwynfi.4

Politics, writing, and the bigger picture

Politics was woven into the fabric of Tudor Hart’s being, and he stood as a Communist Party candidate for Aberavon three times—in 1964, 1966, and 1970. He switched to supporting the Labour Party, and, although unhappy with Tony Blair, he was heartened by the election of Jeremy Corbyn.

Retirement from clinical practice in 1987 gave him time to pursue his interests outside medicine. He moved to the Gower Peninsula, where he grew vegetables, illustrated Christmas cards and books for his grandchildren, and even created a scale model of HMS Beagle. Mainly, however, he was writing and speaking. Described as “absurdly creative and hardworking,” he was prodigious in his output, which included more than 350 peer reviewed papers in all, as well as many books—most famously, A New Kind of Doctor and The Political Economy of Health Care. He held many awards and was a founder member of the Socialist Medical Association and honorary president of the Socialist Health Association. In 2006 he was awarded the Royal College of General Practitioners’ discovery prize for research in primary care.

Tudor Hart straddled the world of intellect and that of a working GP, and generations have benefited from his fresh approach, his unswerving commitment to patients, and his trenchant prose.

Predeceased by a son, he leaves his wife, Mary; five children; and 16 grandchildren.

References

↵Tudor, Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet1971;1:405-12. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X pmid:4100731CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

↵Tudor, Hart J, Humphreys C. Be your own coroner: an audit of 500 consecutive deaths in a general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed)1987;294:871-4. doi:10.1136/bmj.294.6576.871 pmid:3105783Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

↵Tudor, Hart J. Semicontinuous screening of a whole community for hypertension. Lancet1970;2:223-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)92582-1 pmid:4193685CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

↵Tudor, Hart J, Thomas C, Gibbons B, et al. Twenty five years of case finding and audit in a socially deprived community. BMJ1991;302:1509-13. doi:10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1509 pmid:1855023Abstract/FREE Full Text