Like his father before him, Terence Hallinan was prevented from practicing law by the California Bar Association. Vincent Hallinan’s license had been suspended for three years (1957-1960) after he was convicted of federal income tax evasion. Kayo passed the Bar exam in March 1965 but was denied a license until January 1967 because of his arrest record. Both men put up a fight (of course).

Vincent Hallinan wasn’t exactly framed by the feds, but the decision to charge him and his wife as criminals instead of filing a civil suit was vindictive. He had incurred their wrath by defending Harry Bridges and denouncing US intervention in the Korean War when he ran for President in 1952 on the Progressive Party ticket. The IRS spent seven agent-years developing evidence against the Hallinans. At their trial in 1953, the prosecutor made use of a secret FBI report on prospective jurors. The heaviest charge was improper deduction of gifts as business expenses, starting with the $800/month paid to Vince’s father Pat as secretary of the family real estate corporation —and then, after his death, paid to Vince’s mother Lizzy, who was in a high-end rest home. Vince testified, “What I pay my father for his services is nobody’s business but ours. To earn it he did everything that the ordinary corporate executive does except that he didn’t play golf.” Hallinan also cited legal precedent for continuing payments to an executive’s widow.

McCarthyism was still at its peak and newspapers had a field day listing Vivian’s contributions to organizations that the Attorney General listed as pro-communist, along with the cost of her fur coats, shoes, and jewelry. She cited her impeccable business records as general manager of the corporation and the fact that she had never participated in preparing the Hallinans’ joint tax returns. The jury acquitted her, but Vince was convicted of a $37,ooo underpayment between 1946 and 1950. He was ordered to pay $622,000 in penalties, fines, and court costs, and sentenced to 18 months in prison. While he was gone, Vivian was diagnosed with uterine cancer. Here funds were frozen by the government and she had to borrow money to pay for the radiation treatments at Stanford that saved her life.

It was Vince’s second stint at McNeil Island. He was elected head of the inmates’ organization and pressured the warden to enforce President Eisenhower’s desegregation order. He submitted a detailed critique of prison conditions to a US Senate subcommittee that concluded, “There should be an end to the conscious program designed to degrade and humiliate the convicted man to the last extent. A prison as operated in these United States is a symptom of a diseased social system.” When he got out the California Bar Association suspended his license for three years, citing “moral turpitude.” He could have been disbarred, given his felony conviction; but Hallinan wan’t grateful. He appealed to the state Supreme Court, arguing in vain that his conviction “for keeping my own money, not taking someone else’s” was not evidence of moral turpitude.

Terence attended UC Hastings law school and did well, finishing in the top 25% of his class. His main extra-curricular activity was political organizing. “We were all inspired by the black students in North Carolina sitting in at the segregated lunch counters,” Terence recalled. (A sit-in is just what the term implies —people refusing to move until their demand is met. If the police arrest and haul them away, they or their allies resume the action. Publicity around the arrests draws public attention to the situation.) Terence helped plan and took part in sit-ins at car dealerships on Van Ness Avenue (then known as “Automobile Row”) and Mel’s Drive-in, which was owned by a San Francisco Supervisor named Harold Dobbs. He drafted contracts whereby the owners agreed to end discriminatory hiring practices. Getting them signed was the goal of the sit-in. In due course they were all successful.

The sit-ins in San Francisco were the first outside Dixie. Vivian and her sons were regular participants. Police Chief Thomas Cahill said after one round-up of protesters, “Vincent Hallinan was right behind me yelling encouragement all the time we were hauling the family away ‘Atta girl, Vivian!’ If all the Irish stuck together like they did, we could still run San Francisco.” Terence racked up 14 arrests during his law school years, and was convicted of disturbing the peace and unlawful assembly. In the summer of ’63 he was arrested twice in Mississippi while registering voters with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

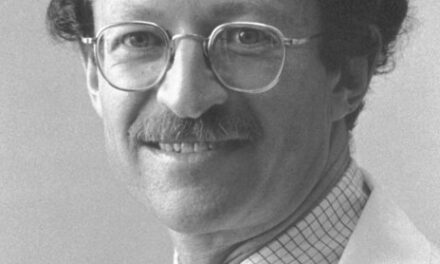

In 1965 he graduated law school and passed the bar exam but the Committee of Bar Examiners would not allow him to practice, citing his arrest record. Hallinan appealed to the state Supreme Court. He was represented by Barney Dreyfus and prevailed by a 6-1 vote. Justice Raymond Peters acknowledged Kayo’s “habitual and continuing resort to fisticuffs to settle personal differences,” but ruled that denying a license to every law student who engaged in a sit-in “would deprive the community of the services of many highly qualified persons of the highest moral courage.”

Judge Peters cited some of the cut men working in Kayo’s corner:

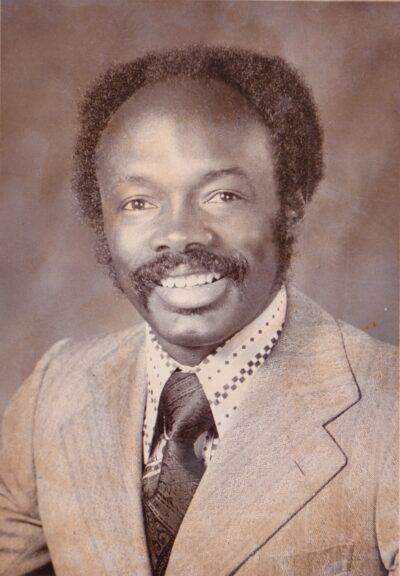

State Assemblyman Willie Brown, also an attorney and with whom petitioner had worked in the civil rights movement, testified that there was nothing in petitioner’s conduct in connection with the movement that would disqualify him from admission to the bar. John A. Burton, also a state assemblyman and an attorney, testified that he had worked with and observed petitioner in various political activities; that petitioner’s conduct during those activities was peaceful; and that he knew of nothing that would disqualify petitioner from admission to the bar.

Joseph R. Grodin, a practicing attorney, taught a course in labor law at Hastings in which petitioner was enrolled. He testified that during that course he found petitioner to be “intelligent, alert, capable of dealing objectively with legal problems.” Nothing in his classroom behavior, in Mr. Grodin’s opinion, indicated anything which reflected negatively upon petitioner’s qualification for the bar. The witness testified to his further opinion that petitioner “would make a very good lawyer.”

“J. Warren Madden, a professor of law at Hastings and a retired judge of the United States Court of Claims, sent a letter recommending petitioner to the Committee of Bar Examiners. He stated in the letter that petitioner was in the top 25 percent of his graduating class, that, while his contacts with petitioner “were not extensive,” he gained the “impression that he was a quiet, serious and intelligent student”; that he, like any person who has passed the bar examination, “has made a large investment of his years and his energy in pursuit of a worthy ambition,” and that if admitted one of petitioner’s principal activities would be “representation of persons whose beliefs are unorthodox or unpopular,” for which type of case, Professor Madden went on to say, there has never been an adequate number of able and willing lawyers.

I had forgotten that Willie Brown got his start in electoral politics so early. He graduated  San Francisco State in 1955, Hastings in ’58, and became an Assemblyman in 1964. As a lawyer he capably defended hookers and people accused of “drug crimes.” Terence once mentioned that Brown had joined the DuBois Clubs in the early ’60s. I didn’t ask for details.

San Francisco State in 1955, Hastings in ’58, and became an Assemblyman in 1964. As a lawyer he capably defended hookers and people accused of “drug crimes.” Terence once mentioned that Brown had joined the DuBois Clubs in the early ’60s. I didn’t ask for details.