Ozempic, Wegovy, and other new anti-obesity drugs have that potential, according to the “medical specialists” Kolata cites. These drugs are “game changers,” according to Jonathan Engel, a historian of medicine and health care policy at Baruch College in New York City. What game is he referring to?

“Obesity affects nearly 42 percent of American adults,” Kolata writes, “and yet, Dr. Engel said, ‘we have been powerless.’ Research into potential medical treatments for the condition led to failures. Drug companies lost interest, with many executives thinking — like most doctors and members of the public — that obesity was a moral failing and not a chronic disease.”

Millions of us know, and Gina Kolata must know, that obesity is a function of high-calory, nutrient-negative food and sedentary lives.

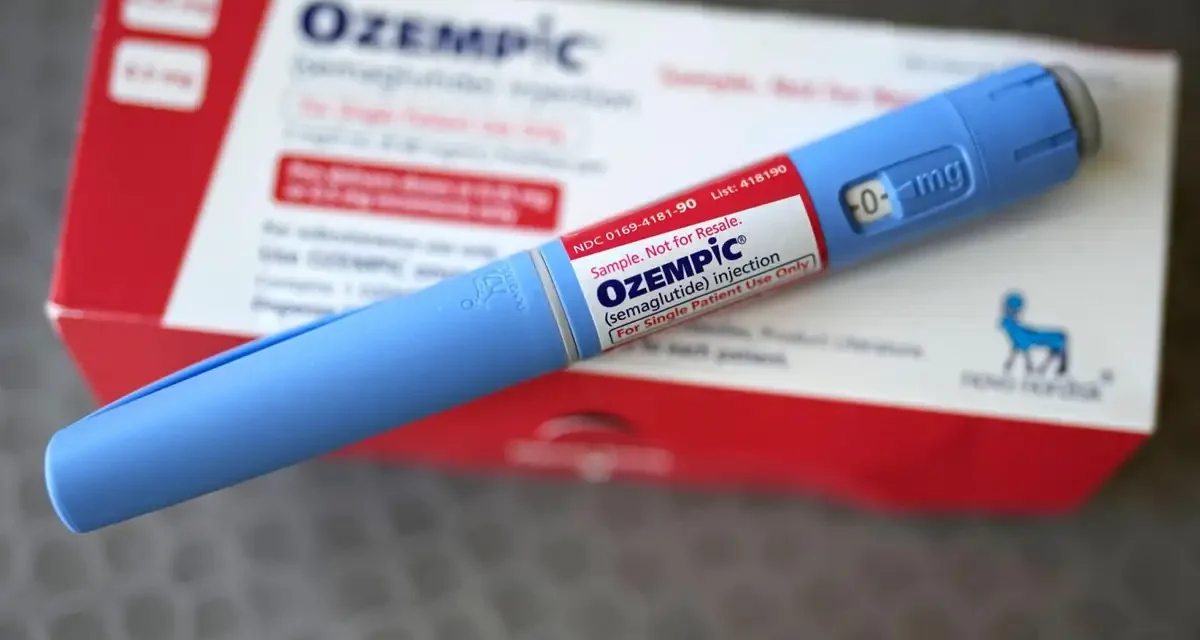

Ozempic was discovered accidentally and the mechanism of action is not understood. In the 1980s Dr. Joel Habener discovered a hormone, GLP-1, that acts only on insulin-producing cells of the pancreas, and only when blood sugar is elevated. Kolata takes us step-by-step through the development, after many years, of a GLP-1 diabetes drug that can be injected only once a week. In 2017 the Danish company Novo Nordisk got FDA approval to market it as “Ozempic.”

People taking Ozempic for type-2 diabetes cut down on food intake and the overweight masses clamored for access. Many asked their doctors to diagnose them as “pre-diabetic” so they could score at the drug store. Novo Nordisk quickly began clinical trials and sought FDA approval as a treatment for weight loss. They got it in 2021. Their weight-loss drug, Wegovy, is simply a higher dose of their diabetes drug, Ozempic.

Kolata has more wonderful news: “Results from a clinical trial reported last week indicate that Wegovy can do more than help people lose weight — it also can protect against cardiac complications, like heart attacks and strokes. But why that happens remains poorly understood.”

GLP-1 drugs expose the brain to hormone levels unseen in nature, a researcher named Seely points our. “Patients taking Wegovy are getting five times the amount of GLP-1 that they would produce in response to a Thanksgiving dinner.” These being novel drugs, novel side-effects might emerge over the years. Many people on Ozempic hit a plateau after which they stop losing weight. But if they quit Ozempic, they tend to regain their weight. So many people will be on it for life

The sound of the cash register is well understood. “In July, doctors in the U.S. wrote about 94,000 prescriptions a week for Wegovy compared with about 62,000 a week for Ozempic.” Everywhere demand exceeds supply. Novo Nordisk is ramping up production and limiting distribution to Norway, Denmark, Germany and the United States.

Eli Lilly is expecting FDA approval for a GLP-1 diabetes drug on which people can lose 20 percent of their weight. “No one fully understands why,” a Lilly scientist tells Kolata.

She ends on a joyful note: “The era of ‘just go out and diet and exercise’ is now gone,’” said Dr. Rudolph Leibel, a professor of diabetes research at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “Now clinicians have tools to address obesity.”

The tools to address obesity are have always been nutritious food and physical activity.