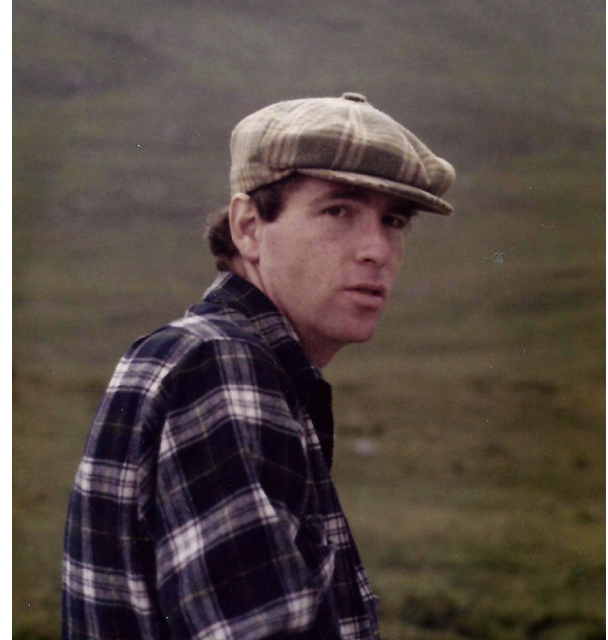

Family and friends of Patrick McCartney gathered at the edge of Donner Lake on Sunday, July 30, to remember him. Pat died unexpectedly last November, at age 68. There were friends from when he was growing up near San Diego and from his days as a newspaperman in the Sierra foothills and from his 20 years of covering the medical marijuana movement (now known as “the industry”) and friends from the Truckee-Donner Historical Society and friends from the small lakeside community in which he had settled. The cabin Pat rented was almost visible from where the wake was held. A co-worker from K-Mart, where he worked to make ends meet, explained how helpful he had been to her and her children in times of personal crisis. His helpfulness was a common theme. Another was his calm intelligence.

Pat had no way of knowing, when he graduated from college and entered the working world in the 1970s, that journalism was a profession with no longterm future. Newspapers started folding under him. His reportorial skills —his mastery of the Freedom of Information Act, for example— were devalued in the 21st century.

Pat was almost alone among journalists back in 1996 when he decided to make the medical marijuana movement his beat. He interviewed and befriended the protagonists —Dr. Tod Mikuriya, Dennis Peron, Dale Gieringer, Bill Panzer, Valerie Corral, Steve Kubby, Ellen Komp, Michael and Michelle Aldrich— way too many to name. Dr. Mikuriya and I were proud to publish Pat’s sensational exposé about the secret meeting between California and federal law enforcement officials —arranged immediately after we, the people legalized marijuana for medical use— to stifle the new law’s implementation.

Around 2006 Pat signed a book deal with Scribner’s, but his co-author, after getting brought up to speed on the story and introduced to all Pat’s sources, decided he did not want a partner. Pat, who needed cash, agreed to a buy-out. He kept working on his own manuscript. And then he died.

As activist Mikki Norris said at the wake, maybe Pat never declared his book finished because the story itself had no ending. She thought the legalization vote in November, 2016, might have inspired him with a fitting conclusion. Pat exulted in the Yes vote, she said. But he was devastated by the election of Donald Trump. Somebody even suggested that he died of a broken heart.

What follows is from the little booklet shared by Pat’s brother Mike and sister Sharon at the wake. Was there ever a cuter kid?

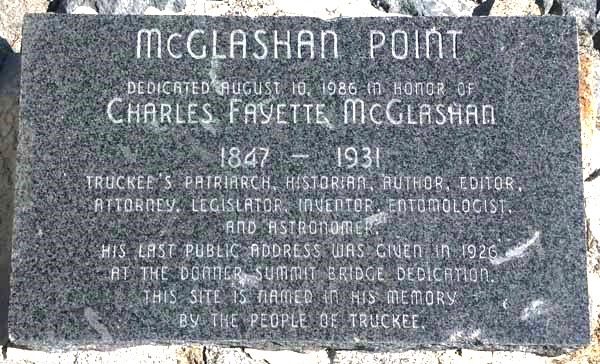

On the drive back Dale Gieringer and I stopped to take in the view from Donner Summit. A group of bikers had just arrived and somebody was asking, “Who’s got the pot?” The overlook featured a plaque honoring Charles McGlashan, “Truckee’s patriarch.” Back home I read about McGlashan in the pamphlet by Stephen Harris, one of Pat’s friends from the Historical Society, that Harris had given out at the wake.

Newcomers to Truckee soon learn what locals know: that the town once had a sizeable Chinese population. According to the 1870 census, as many as one-half of the total residents were from China. Also known as ‘Celestials’ (after their so-called ‘heavenly kingdom’ in China), many thousands of Chinese had come to the shores of California during the gold rush. They came not only to mine the metal like other immigrants, but also to flee the desperate conditions of the ‘Tai Ping’ Rebellion– a calamitous civil war then ongoing in their own homeland. They spread to mining camps all over the Sierra, including some in the Truckee area. Some of them also became merchants, professionals, and laborers, and in the process formed the precursors to the later “Chinatowns”. Then after the gold supply declined, they faced difficult times like most other settlers. But soon construction of the Transcontinental Railroad was underway –by Presidential decree in1862– and a great labor force was needed for the enterprise. After some initial reluctance, the Central Pacific railroad company hired many thousands of unemployed Chinese already in California. And, because they proved to be such good workers, the company also contracted for thousands more to emigrate from China.

But after the railroad was completed– when the golden spike was driven at Promontory Utah in May of 1869– the Chinese once again faced hard times, as their labor was no longer needed. With their own country still in dangerous political turmoil, they could not safely return home –so they sought work as laborers of all sorts in America. At this time some 1400 came back to Truckee, where they had worked during a critical phase of railroad construction, seeking jobs as cooks, woodcutters, laundrymen and any sort of menial labor that might be available. Though initially tolerated by white settlers, the strange-looking orientals were soon regarded with resentment and hostilty by the Caucasians– principally, it was claimed, because of their threat to white job-seekers. Thus began a prolonged effort toward expulsion of the Chinese, from Truckee, from California, from the Western United States altogether. With the battle-cry “The Chinese Must Go!” the citizens of various towns and communities organized and implemented schemes for removal of the Chinese. But because violent means were deemed both dangerous and illegal– inciting possible retaliation from armed Chinese and attracting unwanted attention of Federal law enforcement– peaceful methods would have to be developed.

It was Charles F. McGlashan of Truckee, businessman, attorney, newspaper editor and town father, who proposed a solution: a resolute and thorough boycott of all Chinese merchants and laborers, and of all white merchants who themselves did any business with the Chinese. Under McGlashan’s plan, the Chinese would simply be “starved out”, and their Caucasian employers would be boycotted as well. Over a period of several months, beginning in late 1885, the boycott was implemented, and by February of 1886 was declared a success. Without work, money, supplies or business of any kind, the Chinese began leaving in droves– as reported throughout January of 1886 by McGlashan’s newspaper, the Truckee Republican– on foot, in wagons, by stagecoach and railway, back to coastal cities, and thence, presumably, back to China. By February 3, the paper opened a series of announcements with the declaration that “The departure of the Chinese being a fixed fact…”, and proceeded to state that “The first war cry bows to the victorious cry of triumph” in the campaign to expel the Chinese.

So successful was the boycott that it became known throughout the West as “The Truckee Method”, and soon other towns were implementing their own versions of it. These were often celebrated with a torchlite parade, as had been held by the white citizens of Truckee. On February 13, the Truckee Republican declared: “Tonight we rejoice not only over our own success, but over the success attending the efforts of the entire coast, in getting forever rid of the accursed blot…” And on February 17 reported that “Truckee was a blaze of light…[We are] confident that the entire work will, in a few days at most, be accomplished wholly and entirely.”

Finally, on March 31, after the town had celebrated with a grand finale of “Bonfires, Torches and Enthusiasm”, the newspaper proclaimed: “Monday night [March 29] was, and will ever remain, a red-letter night in the history of the Chinese movement… Truckee feels proud of her assigned position, as the banner town of the Golden State.”