Numerous government agencies have been working hard to implement California’s “legalization” law that takes effect next year. Contrast the bureaucats’ activity with their response to California voters passing legalizing cannabis for medical use, when they did less than zero. Passing an initiative is only half the battle, it turned out. Implementation is everything.

In 1996, California’s top Law Enforcers actually tried to get Prop 215 overridden by the feds. As journalist Pat McCartney wrote in O’Shaughnessy’s, “Documents obtained by this reporter from state and local agencies, and litigants in the Conant v. McCaffrey case, reveal California officials committing acts of covert opposition to the new state law —including appeals for federal legal intervention to undermine it.” (See McCartney’s great scoop, below.)

Pat McCartney died unexpectedly last year —a terrible loss for his family, his many friends, and the medical marijuana movement on which he had focused his reporting. Left unfinished was the history of the movement that he had been working on. The manuscript and Pat’s trove of photographs and documents will be made available if and when the right writer is found. (Contact editor@beyondthc.com if you’re interested.)

McCartney was a skilled and intrepid researcher. Through the Freedom of Information Act he obtained documents describing a meeting held in Washington, DC, at which California officials, federal agency leaders, and strategists from Prohibitionist NGOs made plans to block or limit the law created by the voters. Some of these remarkable memos are being published here for the first time.

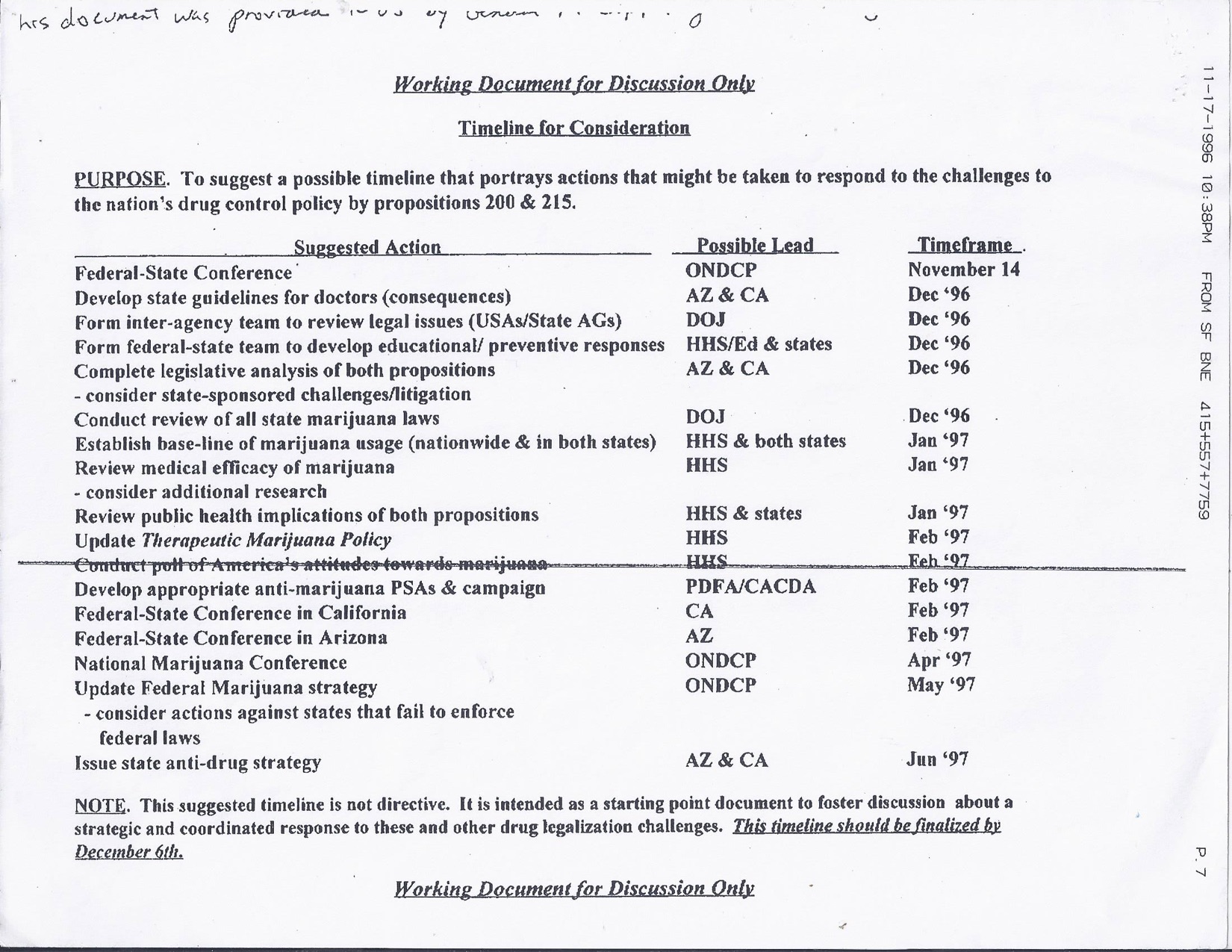

Note that the Drug Czar’s “Timeline” made it a high priority to “Develop state guidelines for doctors (consequences).”

The DIS-implementation of Prop 215 by Pat McCartney

It was no secret, in the summer and fall of 1996, that California law enforcement officers were leading the opposition to the medical marijuana initiative, Proposition 215. Orange County Sheriff Brad Gates headed Citizens for a Drug Free California, the official No-on-215 campaign committee; 57 of the 58 district attorneys urged a “No” vote; and Attorney General Dan Lungren wrote the “No” argument in the Voters Guide, warning that the new law would “exempt patients and defined caregivers” from legal sanction.

After the medical marijuana initiative passed (by a 56-to-44 margin, creating Health & Safety Code Section 11362.5), the opponents had a fundamental choice: try to block full implementation, or accept the will of the voters.

Many in law enforcement chose the obstructionist approach. Numerous documents obtained by this reporter from state and local agencies, and litigants in the Conant v. McCaffrey case, reveal California officials committing acts of covert opposition to the new state law —including appeals for federal legal intervention to undermine it.

In a recent interview, former California Attorney General Dan Lungren defended the post-215 actions of California law enforcement, insisting that his office exercised its best judgment in devising a “narrow interpretation” of the landmark measure. Although Lungren admitted that it was his Constitutional duty to uphold state law against a federal challenge, he would not acknowledge that dealings between his staff and federal authorities had a contrary purpose.

He now says that his goal was to reconcile the state and federal laws. “You don’t go looking for conflict” with federal law,” Lungren said. “You try and resolve conflict, you try and see where the laws can work in conjunction with one another.”

The AG’s “Narrow Interpretation”

At 12:01 a.m., November 6, 1996 —the day cannabis became legal for medical use in California— Lungren faxed a memo to every district attorney, sheriff and police chief in the state, summoning them to an “Emergency All-Zones Conference” in Sacramento Dec. 3 to discuss the new law.

Lungren’s Nov. 6 memo identified a number of factors that officers should consider in determining if probable cause for an arrest existed when evaluating an individual’s claim of medicinal use.

The memo advised police to look for the usual kinds of evidence that established illicit trafficking, including observed sales, the quantity and packaging of marijuana, the presence of cash or pay-owe sheets, evasive tactics, the presence of scanners or weapons, and the suspect’s criminal history.

Although the Nov. 6 memo referred to the police establishing probable cause before arresting a medical cannabis user, it also suggested an interpretation of the initiative that would eliminate the need to prove probable cause: “The proposition may create an affirmative factual defense in certain criminal cases.”

If the Compassionate Use Act merely provided those who used cannabis as medicine a defense in court, nothing would prevent police and prosecutors from arresting and charging as usual.

In the Nov. 6 memo, Lungren promised the California law-enforcement community that he would consult with federal officials “to determine how they will enforce federal law.” In a CNN “Crossfire” appearance Nov. 20, Lungren added that he was conferring with federal officials so “that we would all be on the same page.”

In his public statements Lungren attacked the wording of the medical marijuana initiative —as if the obstacles to implementation were technical, and the fault of the authors. “This thing is a disaster,” he told the Los Angeles Times immediately after it passed. “We’re going to have an unprecedented mess.”

Lungren said the new law would lead to “anarchy and confusion.”

The San Francisco Chronicle quoted Lungren as saying the new law would lead to “anarchy and confusion,” and he promised to “use every legal avenue to fight it.”

Lungren’s fellow Republican, Gov-ernor Pete Wilson —who had vetoed medical-marijuana bills passed by the state legislature in 1994 and ‘95— also denounced the wording of the new law. “It is so loose it is a virtual legalization of the sale of marijuana,” declared the governor.

Meanwhile, back in Washington...

At the Office of National Drug Control Policy in Washington, director Barry McCaffrey was hearing from outraged drug warriors and politicians. Unless he contained the fallout from the California and Arizona initiatives, the drug czar risked being grilled about who “lost” California. The easiest target to blame was financier George Soros, who contributed heavily to both state initiatives. Without professional signature drives funded by Soros, Prop 215 would not have qualified for the ballot in 1996, nor would a reform measure in Arizona.

“It’s not paranoia on my part,” McCaffrey told A.M. Rosenthal, an influential New York Times editor alarmed by the success of the medical-pot initiatives. “I see [the vote in California and Arizona] not as two medical initiatives dealing with the terminally ill; I see this as part of a national effort to legalize drugs, starting with marijuana, all over the United States.”

Soros, added McCaffrey, was “at the heart and soul of a lot of this.”

Comparing Soros to a pornographer, Rosenthal asked McCaffrey to denounce him, encouraging right-minded people to shun the billionaire financier.

On Nov. 14, 1996, nine days after California and Arizona voters approved medical-marijuana laws, delegations of law enforcement officials from the two states met with federal drug officials in the nation’s capital.

The officials were not seeking “to implement a plan to provide for the safe and affordable distribution of marijuana to patients…”

A review of the agenda and notes from the meeting suggests that the officials were not seeking, as the California measure directed them, “to implement a plan to provide for the safe and affordable distribution of marijuana to patients…”

Instead, police and prosecutors from the two states asked for federal help in killing the medical marijuana measures.

The California delegation represented a broad cross-section of the state’s law-enforcement establishment. Four key members of Lungren’s staff were at the first and largest of the meetings. Career prosecutor Thomas F. Gede was Lungren’s special assistant and relayed his views. Senior Assistant AG John Gordnier would write the department’s principal analysis of the initiative and later issue a series of “Updates” to California law enforcement.

Special Agent Robert S. Elsberg wore two hats, representing the California Peace Officers Association and the California Chiefs of Police Association. Special Agent Thomas J. Gorman, the opposition spokesman during the campaign while still on the AG’s payroll, attended on behalf of the 7,000-member California Narcotics Officers Association. Before the election, Gorman had written “Marijuana is NOT Medicine” for the CNOA and the AG’s Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement.

[Mikuriya had called Gorman the day after Prop 215 passed with questions about its implementation. Gorman mentioned the meeting coming up on Nov. 14. He also said he was glad the No-on-215 campaign was over, implying that it had been an unpleasant assignment. Mikuriya notified Rep. Ronald Dellums’s office that he wanted to participate in the upcoming meeting, which would be hosted by the Drug Czar. Dellums asked that Mikuriya be invited, but no such courtesy was extended.]

Joining the attorney general’s contingent were representatives from three of California’s most powerful law-enforcement associations: Santa Clara D.A. George Kennedy of the District Attorneys Association; Seal Beach Police Chief Bill Stern of the Chiefs of Police Association; and Santa Barbara Sheriff Jim Thomas and Stanislaus Sheriff Les Weidman of the Sheriffs Association.

Also attending was Orange County Sheriff Brad Gates, who came with a handout from Stu Mollrich, the campaign specialist employed by the No-on-215 campaign. The Gates/Mollrich proposal listed strategies to overturn the California and Arizona voter initiatives.

“Private lawsuits against these initiatives should be filed unless the federal government takes immediate action.”

“Determine the powers of the federal government to preempt 215 and 200.”

“Have law enforcement organizations in each state work with the federal government to implement the strategy.”

“A new political force is needed to fight Soros and his associates. It must be national and ongoing.”

Gates saw a role for himself in the new national campaign. He promoted the idea of a new initiative to rescind Proposition 215 —a trial balloon that would deflate when polling found California voters had little appetite to revisit the issue. Gates would later seek $3 million from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to fund a similar project.

Welcoming the California and Arizona delegations were two-dozen federal officials representing the Office of National Drug Control Policy, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Department of Justice, Health and Human Services, Education, Transportation, Treasury and the National Academy of Sciences. Four U.S. senators, including California’s Dianne Feinstein, sent aides to the meeting.

Also sitting in on the meeting were representatives of several private anti-drug groups —the Partnership for a Drug Free America, the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, and the Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA), the federal government’s most heavily subsidized, “private” anti-drug organization. Joining them was Paul Jellinek, vice president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the a non-profit offspring of a drug company (Johnson & Johnson), and the largest private funding source in the war against illicit drug use.

McCaffrey hosted the event, opening the discussion with prepared remarks entitled, “A National Strategy in Face of the Expanding Legalization Effort.”

The retired four-star general said he did not believe that many doctors would start recommending pot to their patients. Federal law had not changed, he reminded the participants, so enforcing existing law should be a simple task. In notes Elsberg took, he wrote that McCaffrey “wants the state to proceed and not wait for a coordinated action.”

McCaffrey said he was not going to rush into unwarranted actions, but preferred to observe the political fallout from the state measures before taking additional steps. “He inferred [sic] that by waiting approximately one year we could sort through and think through the issues,” Elsberg noted.

Perhaps it was no coincidence that a little more than a year later the Clinton administration would file civil lawsuits against six California cannabis dispensaries. The strategy targeted the only public supply of marijuana available to qualified patients, and by choosing the path of civil litigation, the federal strategists avoided the risk and potential embarrassment of a jury trial.

The first state-federal powwow included three principal topics, according to Elsberg’s notes.

• California and federal law-enforcement policy as a result of Proposition 215;

• Potential legal and legislative challenges to Proposition 215; and

• How to fight the new political war against drug legalization in America.

Nowhere in the agenda is reference made to the explicit conflict between state and federal laws or the implications for California police and prosecutors.

As Lungren said in our recent interview, he had taken an oath to uphold the U.S. Constitution as well as the California Constitution. “You attempt to determine how you can uphold Prop. 215 within the context of the California law, but also within the context of the U.S. Constitution,” Lungren stated. “I don’t see any conflict with that.”

Yet according to Elsberg, the California delegation had come specifically to ask the feds to overturn the law they had so bitterly opposed. “The California delegation was attempting to have the federal government sue the State of California since we felt federal law preempts State’s authority to make something a medicine,” Elsberg notes. “We requested to have the federal government to give California law enforcement a written document authorizing us to seize marijuana under federal authority and for DEA to take a greater role in marijuana enforcement in California.”

On behalf of Lungren, Gede asked the federal government to intervene with a lawsuit. In addition, he asked the DEA to cross-designate some prosecutors and peace officers so they could enforce federal law.

“(Gede) indicated that there was a sense of urgency because we need guidelines for law enforcement, the public and doctors,” Elsberg observed.

District Attorney Michael Bradbury of Ventura County called for a federal-state partnership so that local police could avoid any civil liability for enforcing federal law.

“(Bradbury) wants DEA to reassure state that California should still enforce federal law,” noted ONDCP lawyer Wayne Raabe in minutes he took at the meeting. “Biggest problem is no one knows at what point medical marijuana becomes illegal for distribution. Can’t wait six months for an answer.”

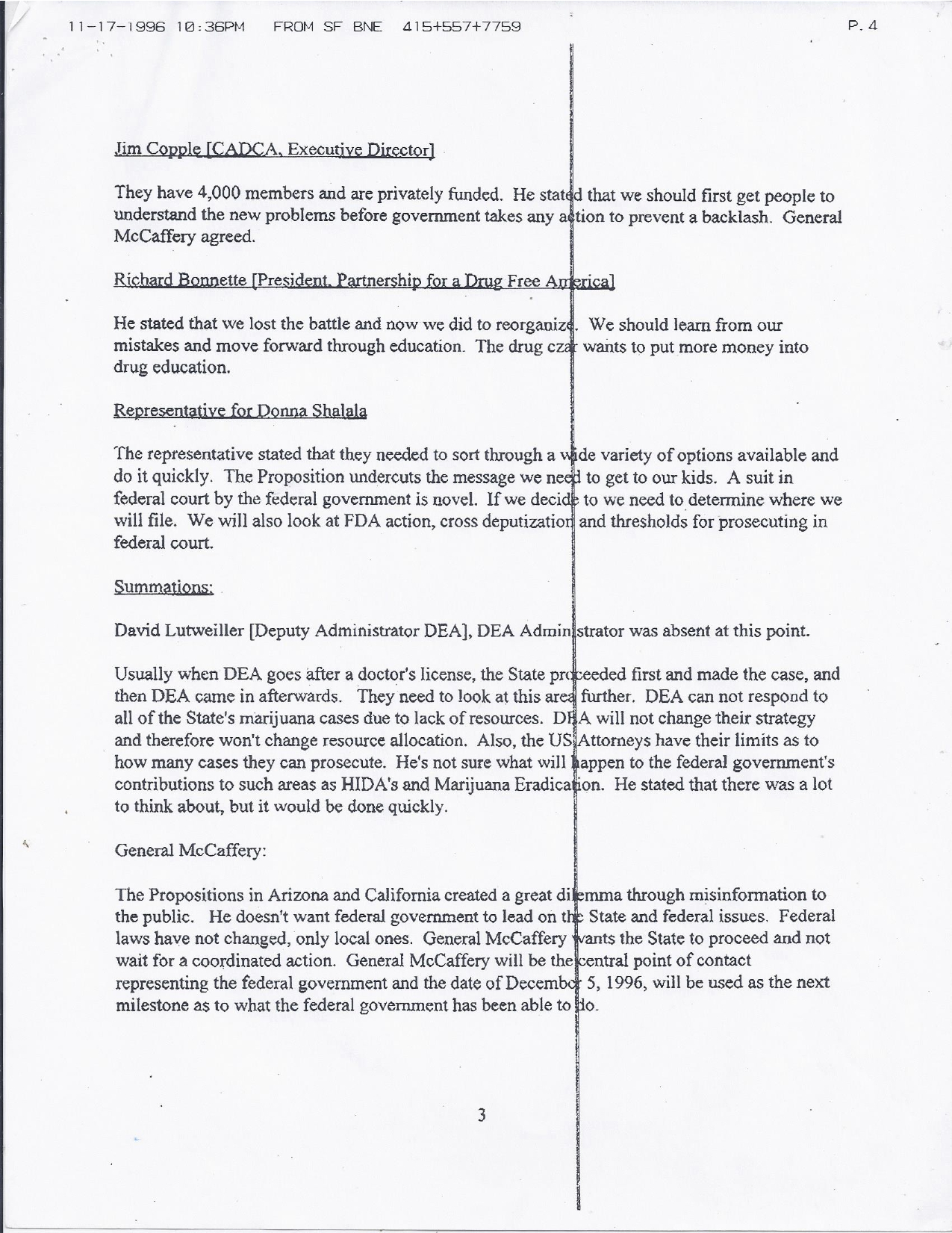

Much of the discussion by the private anti-drug officials who attended the meeting focused on how to prevent the medical-marijuana campaign from succeeding in other states.

“We must protect the other 48 states and rollback in California and Arizona,” said CADCA Executive Director Jim Copple, according to Raabe. “We are taking it very seriously.”

The private anti-drug officials identified money as the essential ingredient in any publicity campaign attacking new initiatives. Copple said CADCA, the Johnson Foundation and the Center for Alcohol and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, run by former drug czar Joseph Califano, could provide the money and expertise to respond to the threat posed by additional medical-marijuana measures.

As the discussion over strategies to defeat the reformists continued, the vice president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation recognized the political nature of the meeting.

“The other side would be salivating if they could hear prospect of feds going against the will of the people,” said Paul Jellinek of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“The other side would be salivating if they could hear prospect of feds going against the will of the people,” said Paul Jellinek according to Raabe’s clipped notes.

In his remarks, DEA Administrator Tom Constantine allowed that federal grand juries would be used to indict major traffickers, and that actions to remove doctor’s licenses would be taken “where appropriate” as a deterrent. California doctors were advised of this threat by McCaffrey and U.S. Attorney General at a nationally televised press conference on Dec. 30.

Constantine also urged conference participants to lobby members of the Senate Judiciary Committee, which had scheduled a December 2 hearing on the new marijuana laws.

At that event, five witnesses denounced the initiatives and only one, Marvin Cohen, treasurer for Arizonans for Drug Policy Reform, defended them.

McCaffrey warned that the measures would “send the wrong message to our children,” and threaten to “undermine our National Drug Control Strategy.”

Lest anyone believe that he had “lost” the California and Arizona elections, McCaffrey enumerated the actions he had taken during the campaigns. They included contacting 166 business leaders soliciting support for the opposition campaign, meeting with editorial boards and giving 35 interviews. On his two visits to the battleground states, McCaffrey had conducted eight press conferences and attended four political rallies.

Sheriff Gates told the senators that the authors of Proposition 215 had written “irresponsible loopholes” that would allow cannabis clubs to operate with impunity.

“And they cannot claim that the legislature will close the loopholes – it can’t,” the Orange County sheriff testified. “Because this is a ballot initiative and contains no provisions for amendment by the legislature, another vote of the people would be required to close the loopholes and that could not happen for at least two years.”

Gates urged the senators to launch a federal challenge to California’s law.

“I strongly believe that the federal government should assert its authority, through the federal courts, and sue to have the two state propositions overturned on the grounds of federal supremacy,” Gates said. “Only then will we regain the ability to enforce a national drug policy.”

Lungren’s “Emergency” Meeting

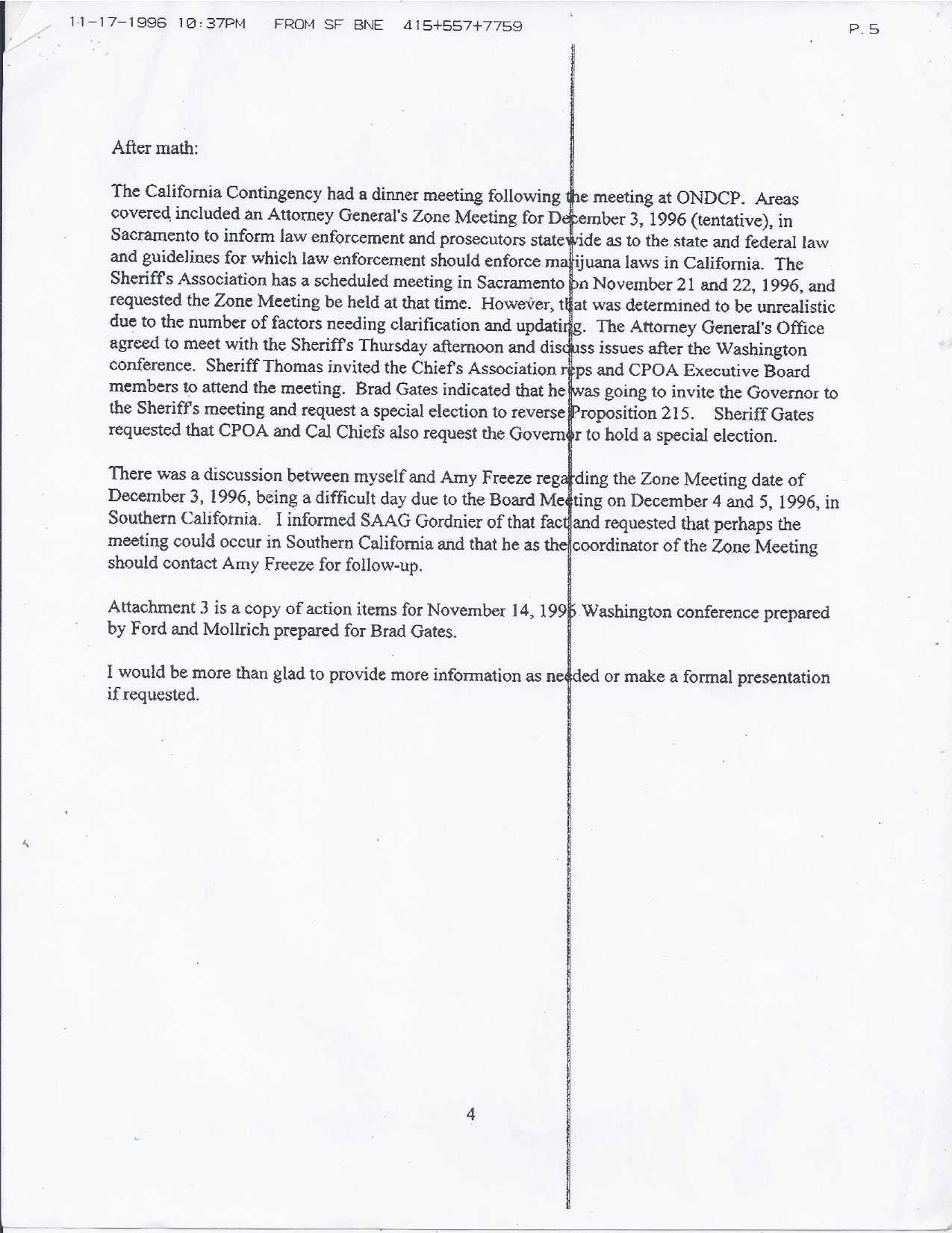

Lungren’s “emergency all-zones conference,” held on Dec 3 in a ballroom at the Sheraton Grand in Sacramento, was an expanded version of the annual meeting the California District Attorneys Association holds every December. Among the 300 attendees were 27 of the state’s district attorneys, 22 sheriffs, and 15 police chiefs. Accompanying them were another 145 peace officers and prosecutors representing 60 cities and 55 of California’s 58 counties.

Also present, according to the sign-in roster, were more than two dozen agents and administrators from Lungren’s office; eight representatives of the Governor’s Office of Criminal Justice Planning, which administers federal anti-drug money; five officials with the Office of Emergency Services; and representatives of various other law-enforcement agencies and associations, including the Department of Alcohol & Drugs, the California Highway Patrol, the Western States Information Network, the California State University Police Department, California State Sheriffs Association, Board of Corrections, Bureau of Prison Terms and, of course, the 7,000-member California Narcotics Officers Association.

Sitting in on the gathering was a small contingent of federal law enforcement from the Sacramento region, including Assistant U.S. Attorney Nancy Simpson of the Eastern District, and DEA agents Stephen C. Delgado and Ron Mancini.

The public and advocates for medical marijuana were excluded. Journalist Fred Gardner had taken a day off from work at UCSF to accompany San Francisco District Attorney Terence Hallinan. He was escorted out of the banquet room as the proceedings began. (Four years later Gardner joined the ranks of law enforcement as SFDA’s public information officer.)

No speaker defended the new law, although Hallinan took the floor during a question period to say it could work.

No speaker on the two scheduled panels defended the new law, although Hallinan took the floor during a question period to say it could work. He advised his law enforcement colleagues to transfer responsibility for implementing it to their county health departments.

The day’s first panel spelled out how local police and prosecutors should respond to the new law. District Attorney Mike Capizzi of Orange County, once the nominal co-chair of the opposition campaign, advised the assembled prosecutors that they could still charge medical users with offenses not specifically exempted by the initiative. In fact, he added, they could still prosecute offenses named in the measure.

“There’s no reason to concede” charges of possession for sale or furnishing marijuana, Capizzi told the gathering. One handout at the meeting summarized the impact of Proposition 215 on existing Health & Safety Code sections.

Attorney Diana L. Field summarized Capizzi’s position in a memorandum to the California Police Officers Association. “In the meantime, the view of the Orange County District Attorney’s Office is that police and prosecutors should continue to provide vigorous enforcement of the laws as written,” Field informed the association’s 3,600 members.

The linchpin of the state response that day was “Proposition 215: An Analysis,” written by Senior Deputy A.G. John Gordnier. The 13-page opinion effectively advised police and sheriffs to continue arresting medical users. The new law would not protect a medical user from either arrest or prosecution, according to Lungren’s top aide —as if voters intended patients to go to jail and defend themselves in court in order to use their medicine.

Gordnier cautioned, however: “Because of the language of Section 11362.5 (b)(1)(B), some defense counsel will contend that the statute is an exemption from prosecution as to patients and caregivers.”

To this day Dan Lungren maintains that Prop 215 only created an affirmative defense, not a bar to prosecution. The authors may have intended it to protect patients from arrest and prosecution, he said, “but the choice of language went the other way.”

The disdain of law enforcement for medical marijuana was exemplified by the distribution at the All-Zones meeting of “Say It Straight,” a paper prepared by CADCA, asserting “There are over 10,000 scientific studies that prove marijuana is a harmful addictive drug. There is not one reliable study that demonstrates marijuana has any medical value…” And “The harmful conse-quences of smoking marijuana include, but are not limited to the following: premature cancer, addiction, coordination and perception impairment, a number of mental disorders, including depression, hostility and increased aggressiveness, general apathy, memory loss, reproductive disabilities, and impairment to the immune system …”

As one of the final acts of the All Zones Meeting, Lungren appointed a “Proposition 215 Working Group” that would include state narcotics officers, district attorneys, sheriffs – and federal Assistant U.S. Attorney Simpson and two DEA agents.

Another Meeting in D.C.

Two California law-enforcement officials attended a second meeting in Washington on December 6, 1996, while others participated by teleconference. Although federal officials have provided no minutes from the meeting, a memorandum issued by the drug czar’s office recounted the goals adopted and actions taken by the interagency working group and the delegations from California and Arizona.

According to the memo, federal officials wanted to reaffirm the authority of the Food and Drug Administration to approve new medicines; to research the possible violation of international drug treaties; and to link funding for local law enforcement to a state’s compliance with federal drug laws. In addition, federal agencies would seek to “blunt the negative consequences” of the state initiatives, “including obtaining the repeal of Propositions 200 and 215 and other ‘medical marijuana’ or similar provisions already passed in other states.”

Federal authorities would also “provide guidance and assistance to law enforcement in California and Arizona,” the memo stated without spelling out what the assistance might include.

The memo described actions by Sheriff Gates to recruit political and corporate support for repealing Proposition 215 through a competing initiative in 1998. The memo also cited Mollrich’s effort to create a national organization to fight other “legalization” campaigns, and the hiring of the Orange County law firm of Rutan and Tucker to study the prospects of overturning the California measure by a lawsuit.

In the analysis paid for by CADCA, the firm’s lawyers concluded that an attempt by Congress to preempt the initiative under the Supremacy Clause “may be met with significant hurdles.” The attorneys advised that it would be easier for Congress to amend the Controlled Substances Act to prohibit physician “recommendations” than to overturn the medical-marijuana measure on its own.

Allowable Quantity

The final piece of Lungren’s policy toward medical marijuana came two months later on February 2, 1997, when his Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement issued the “Peace Officer Guide: Compassionate Use Act of 1996.” In a fateful discussion of patient qualifications, the guideline relied on narcotic-agent arithmetic to declare most medical users guilty of growing and possessing too much medicine:

“Note: One marijuana plant produces approximately one pound of bulk marijuana. One pound will make approximately 1,000 cigarettes. Therefore, one can argue that more than two plants would be cultivation of more than necessary for personal medical use.

“Health and Safety Code Section 11357 provides that any amount less than 28.5 grams should be deemed for personal use. Generally, one gram will make two marijuana cigarettes; quantities over this amount may be more than necessary for personal medical purposes.”

Lungren gave authority to arrest and prosecute close to 100 percent of medical users

In a single stroke, Attorney General Lungren’s office had given the authority to police officers to arrest close to 100 percent of medical users, and for district attorneys to prosecute them. The analysis also paved the way for the prosecution of the cannabis dispensaries springing up around the state, by declaring that only individuals could meet the law’s definition of a primary caregiver.

The appearance of cannabis clubs after the election especially bothered Lungren. As far as he was concerned, Proposition 215 did not authorize anyone to sell marijuana. When I asked Lungren if he believed that voters intended patients to be subjected to arrest and prosecution, he avoided a direct answer by posing a different question.

“I don’t believe, if you ask me that question, whether the people who voted for it expected that there would be cannabis buyers clubs around the state,” Lungren said. “There was no mention whatsoever about that. And I suspect had there been in the initiative, the initiative would have gone down.”

But media coverage during Prop 215 campaign had focused on Dennis Peron’s San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club, which Lungren made the object of statewide attention during the campaign when he ordered the Bureau of Narcotics to raid and close it on August 4, 1996.