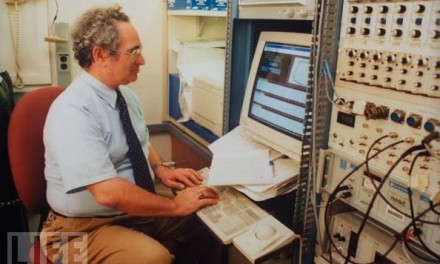

Dr. Shigeaki Hinoharam died in Tokyo on July 18 at the age of 105. It took great restraint not to boldface half the lines in the New York Times obit by Sam Roberts. Extensive excerpts follow:

Dr. Shigeaki Hinohara, who cautioned against gluttony and early retirement and vigorously championed annual medical checkups, climbing stairs regularly and just having fun — advice that helped make Japan the world leader in longevity — died on July 18 in Tokyo. Dutifully practicing the credo of physician heal thyself, he lived to 105…

Dr. Hinohara was born in 1911, when the average Japanese person was unlikely to survive past 40… He ministered to victims of the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. He was taken hostage in 1970 when Japanese Red Army terrorists hijacked a commercial jet. He was able to treat 640 of the victims of a radical cult’s subway poison gas attack in 1995 (all but one survived), because he had presciently equipped his hospital the year before to handle mass casualties like an earthquake.

He also wrote a musical for children when he was 88 and a best-selling book when he was 101. He recently took up golf. Until a few months ago he was still treating patients and kept a date book with space for five more years of appointments.

In the early 1950s, Dr. Hinohara pioneered a system of complete annual physicals — called “human dry-dock” — that has been credited with helping to lengthen the average life span of Japanese people. Women born there today can expect to live to 87; men, to 80.

In the 1970s, he reclassified strokes and heart disorders — commonly perceived as inevitable adult diseases that required treatment — to lifestyle ailments that were often preventable.

Dr. Hinohara insisted that patients be treated as individuals — that a doctor needed to understand the patient as a whole as thoroughly as the illness. He argued that palliative care should be a priority for the terminally ill.

He imposed few inviolable health rules, though he did recommend some basic guidelines: Avoid obesity, take the stairs (he did, two steps at a time) and carry your own packages and luggage. Remember that doctors cannot cure everything. Don’t underestimate the beneficial effects of music and the company of animals; both can be therapeutic. Don’t ever retire, but if you must, do so a lot later than age 65. And prevail over pain simply by enjoying yourself.

“We all remember how as children, when we were having fun, we often forgot to eat or sleep,” he often said. “I believe we can keep that attitude as adults — it is best not to tire the body with too many rules such as lunchtime and bedtime.”

Dr. Hinohara maintained his weight at about 130 pounds. His diet was spartan: coffee, milk and orange juice with a tablespoon of olive oil for breakfast; milk and a few biscuits for lunch; vegetables with a small portion of fish and rice for dinner. (He would consume three and a half ounces of lean meat twice a week.)

Dr. Shigeaki Hinohara was born on Oct. 4, 1911, in Yamaguchi Prefecture, in western Japan. He decided to study medicine after his mother’s life was saved by the family’s doctor. His father was a Methodist pastor who had studied at Duke University…

“Have big visions and put such visions into reality with courage,” his father had advised him, Dr. Hinohara told the Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network. “The visions may not be achieved while you are alive, but do not forget to be adventurous. Then you will be victorious.”

Dr. Hinohara graduated in 1937 from Kyoto Imperial University’s College of Medicine. (He later studied for a year at Emory University in Atlanta.) He began practicing at St. Luke’s International Hospital in 1941. (It was founded by a missionary at the beginning of the 20th century.) He became its director in 1992.

In 1970, he was flying to a medical conference in Japan when his plane was hijacked by radical Communists armed with swords and pipe bombs. He was among 130 hostages who spent four days trapped in 100-degree heat until the hijackers released their captives and flew to North Korea, where they were offered asylum.

“I believe that I was privileged to live,” he later said, “so my life must be dedicated to other people.”

After spending his first six decades supporting his family, Dr. Hinohara devoted the remainder of his life largely to volunteer work.

In 2000, he conceived a musical version of Leo Buscaglia’s book “The Fall of Freddie the Leaf,” which was performed in Japan and played Off Off Broadway in New York. He wrote scores of books in Japanese, including “Living Long, Living Good” (2001), which sold more than a million copies.

Until the last few months, he would work up to 18 hours a day. Using a cane, he would exercise by taking 2,000 or more steps a day. In March, unable to eat, he was hospitalized. But he refused a feeding tube and was discharged. Months later, he died at home.