December 25, 2003

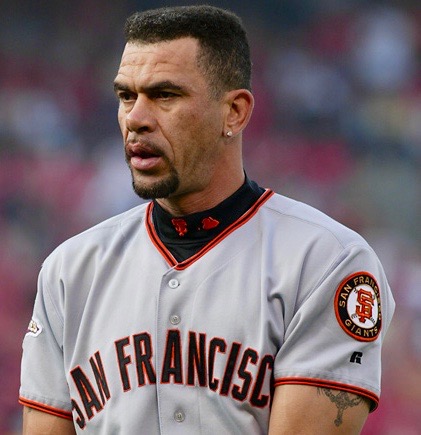

This week the Giants’ catcher Benito Santiago was humiliated in the media after a Puerto Rican customs official detected marijuana (2 oz) in a package addressed to him. Last month Damon Stoudamire and Rasheed Wallace of the Portland Trailblazers were busted for possession as they drove home from Seattle after a game. Hardly a week goes by without a story linking some superb athlete to the supposedly debilitating weed.

The professional basketball players —some of whom have enduring loyalties to brothers back on the streets— missed an opportunity to take a stand in support of their drug of choice when the collective bargaining agreement was renegotiated in 1999. Under the old contract, NBA rookies could be tested randomly for cocaine and heroin; veterans could be tested only if there was reasonable suspicion they were using. There was no provision forbidding marijuana use, and at the time, according to Selena Roberts of the New York Times, about two-thirds of the players smoked pot as a post-game analgesic and relaxant.

Among those who’d been exposed were Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the leading scorer in NBA history (caught with six grams while trying to clear customs at the Toronto airport); Robert Parrish, then the oldest player in the league (and one of the best over the course of his career); Allan Iverson; Marcus Canby; Isaiah Rider… In August ’98 Chris Webber was caught with less than half an ounce in his luggage while passing through the airport in San Juan (costing him his deal with Fila).

When contract negotiations began in the Spring of ’99, Players Association President Billy Hunter was surprised by the force with which league

officials pushed for marijuana testing. Instead of insisting that frequent marijuana use need not be debilitating —Jabbar and Parrish are living proof, and that the players had rights to health, happiness, privacy, etc.— Hunter and player rep Patrick Ewing yielded to Commissioner David Stern’s lawyers. They agreed that all players —and coaches and courtside personnel— would submit to peeing in the cup. Hunter told TV reporter Armen Keteyian “We traded it off for something more important. Right now, I don’t quite remember what… We did what we had to do to help enhance the image of our players. The appearance was that many of them engaged in the use of marijuana. The NBA had been pleading or crying for an expanded drug program for years, so we took the high road and acquiesced.”

According to the agreement, rookies could be tested for mj at any time, but no more than once during training camp and three times during the season. Veterans faced random testing once during the season. First time offenders would have to undergo counseling. Second-time offenders would be fined $15,000. Subsequent violations would result in five-game suspensions.

NBA spokesman Brian MacIntyre crowed at the time, “Kids look up to us. This is the right thing to do.” Poor Patrick Ewing said, “The press asked for it, the commissioner asked for it, we used it during the bargaining session to get something we wanted. We gave it up, that’s it. No sense crying about it.”

But there’s an ongoing cost to the players —in addition to the periodic humiliations— in that their individual bargaining power is eroded by

marijuana “offenses.” Take, for example, the L.A. Clippers great small forward Lamar Odom, who has tested positive twice now, and had to serve a five-game suspension. When next he negotiates a contract, the owners will say they’re doing him a favor allowing him to remain in the league, given his terrible tendency to sin, and will save themselves millions.

And the pressure to test more often and more rigorously will increase if word ever gets out that marijuana is a performance enhancer. Recall that Canadian Ross Rebagliati won the Olympic snowboarding championship in Nagano, Japan, then had his medal revoked, then was reinstated as champion when the IOCC concluded that, given its adverse effects on motor coordination, marijuana couldn’t possibly have helped Rebagliati. The truth is, marijuana can make you looser, which is why many snowboarders (and hoopsters) don’t consider it a no-no. Maybe it costs you your edge, but that’s not always a bad thing.

Jason Jason Williams

son of the custodian

played in the gymnasium

after it closed

Horse of course and one on one

Older brother used to back him down

Jason had to learn his own

spectacular moves

Practicing with ankleweights

Crossovers through the nights

no looks and behind the

out-of-sight and off the walls

He hung with Randy Moss

He smoked till he got tossed

He said you ain’t my boss

and they made him pay the price —twice

Jason Jason Williams

Tall enough and sneaky fast

Dude can shoot your eyes out

but he’d rather pass

To Chris Webber on the wing

Williamson following

he’s got the ball on a string

Alley-oop… at the hoop….

Here come the gallant Serbians

who wouldn’t be subservient

cheered on by suburbians

like they opposed the war

And Max, cast off as mad

and Barry with his famous dad

FUNDERBURKE!, Abdul Wahad,

a diverse crew whose

passing got contagious

forgiving and courageous

totally outrageous

Well ain’t that the point of

Jason Jason Williams

Wiry, working class

dude can shoot your eyes out

but he’s come to pass.

Add Humiliations

Two uniformed police officers appeared at Tod Mikuriya’s house in the Berkeley Hills at 7:30 a.m. Monday 12/23 to arrest him (in front of his

8-year-old daughter) on a warrant from San Mateo County. In late November Mikuriya had been asked by a lawyer named Barry J. Rekoon to testify that he had indeed approved cannabis use by Robert Whitaker, 50, who had been arrested on cultivation charges. Mikuriya requested reimbursement as an expert witness ($2,000/day). Rekoom refused, and made a motion in SuperiorCourt that Judge Mark Forcum subpoena Mikuriya as a percipient witness ($15/hour). Mikuriya, who recently underwent triple-bypass heart surgery, wrote a letter to the judge “saying I had no problem with testifying if an arrangement could be made for my fee. And that’s where I thought it stood until Berkeley’s finest showed up this morning to take me into custody.”

The dignified 69-year-old physician was booked at BPD headquarters and released by mid-morning. The episode brought to mind a story about Charlie Chaplin. At the height of the McCarthy period the great comedian fled the U.S. for Switzerland and for a while his assets were inaccessible in a Beverly Hills bank. The Red Chinese government offered Chaplin $1 million for the rights to screen his films. Chaplin reportedly wired Premier Chou En Lai, “$1 million not nearly enough. What do you think I am, a Communist?”

Frist Family Values

The family of Sen. Bill Frist of Tennesseee, the transplant specialist who has just become the Republican majority leader in the Senate, owns Hospital Corp. of America, an HMO that has paid the government $1.7 billion in fines stemming from Medicare overbilling and other forms of healthcare fraud. (Just imagine how much HCA got to keep.) Although Sen Frist has played no direct role in running HCA, he invested in it and made a fortune estimated at $20 million. During the last Senate session Frist defended the provision in the Homeland Security Bill restricting lawsuits against Eli Lilly in connection with Thimerosol (a mercury-based vaccine preservative). No legislator has claimed credit for adding the Lilly-loving rider onto the bill. Cassandra sez it was Doc Frist himself.