March 1, 2018 This is to honor Linda Jackson, LVN, whose Oakland clinic —in remote contact with David Hadorn, MD— pioneered the use of telemedicine to evaluate patients for treatment with cannabis. (Every month is Black History month at O’Shaughnessy’s.)

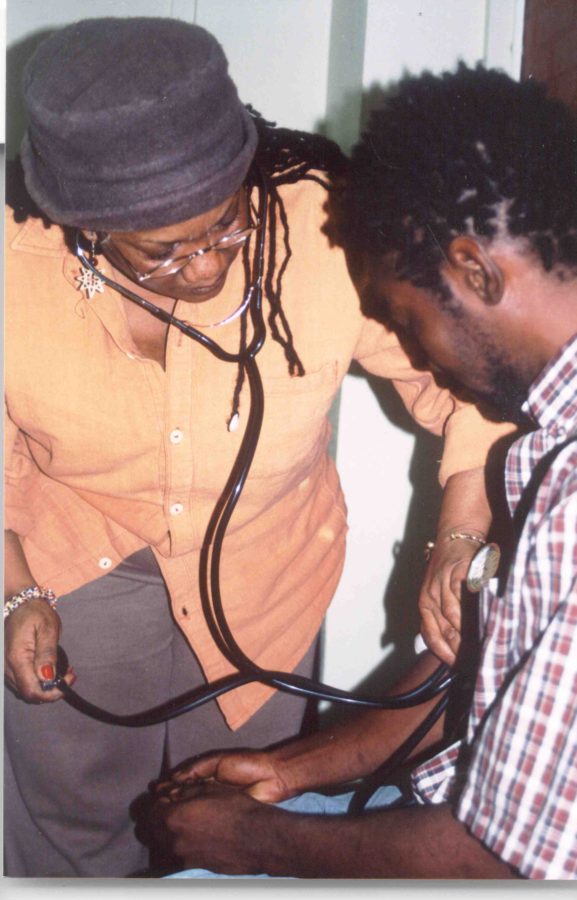

Linda Jackson, LVN, and David Hadorn, MD (on screen) developed a protocol for evaluating patients seeking approval to medicate with cannabis. Photo by Fred Gardner

The year was 2003. Tod Mikuriya, MD, had organized those few physicians issuing approvals for “any condition for which marijuana provides relief” into the California Cannabis Research Medical Group (now known as the Society of Cannabis Clinicians). The CCRMG had adopted practice guidelines, drafted by Mikuriya, stating that renewals could be issued on the basis of a teleconference, but the initial approval required an in-person visit.

Hadorn and Jackson conducted a study to assess the safety and utility of their approach (in which a nurse conducted the in-person exam and the physician conducted an online consultation). This how they described their intake procedure in a paper written for O’Shaughnessy’s:

“The clinical encounter consisted of two parts. First, patients were interviewed by LJ to determine if they had a reasonable likelihood of being approved by DH for cannabis medicines under CH&S Code #11362.5. Patients typically excluded at this point included those with poorly controlled psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia. These patients were referred to a psychiatrist. No patients under 18 years of age were evaluated or approved, although we are aware of impressive anecdotal information that minors can benefit substantially from judicious use of cannabis medicines. Patients with acute or inadequately evaluated symptoms were also referred elsewhere.

Patients passing these screens were asked to sign two consent forms, the usual permission to treat form and a separate one agreeing to be interviewed by DH via videoconferencing. Patients then completed a thorough intake form covering chief complaint, history of present illness, past medical history, family history, and experience to date with cannabis as medicine. LJ assisted patients as needed and reviewed the form for accuracy and completeness. Any specific points that needed to be brought to the attention of DH were identified.

The patient was then asked to read a three-page description of alternative methods of administering cannabis; tinctures and vaporizers in particular were encouraged in order to avoid any hazards associated with smoking. A brief description was also provided concerning the legal aspects of medicinal cannabis, including the difference between State and federal laws. Patients then took a quiz covering these topics; incorrect responses were reviewed and discussed by LJ.

At this point the videoconference was initiated. LJ reviewed the patient’s intake form with DH, item-by-item, identifying any particular points that needed physician attention or review. During this recitation DH took notes of the key points, using these notes to formulate an initial approach to the interview.”

Hadorn and Jackson hoped that the study framework might provide a defense if the Medical Board of California looked askance, and that the data would convince the CCRMG to revise its guidelines to allow initial cannabis approvals via telemedicine.

In the discussion that ensued, Jeffrey Hergenrather, MD commented:

“I have had a limited amount of experience with telemedicine while a system was tried out in the Warrack Emergency Department, Santa Rosa, CA where I practiced ER medicine for the past 13 years. We were trying to provide a reliable means to work with remote groups around our county including rural nursing homes. My personal take on it was that it was a stop gap measure only suitable for making a judgement call as to whether a patient needed to be seen on an emergent basis or not. I would not favor making this a first line method of making an initial evaluation with a patient. I believe that this interview should be face-to-face, with ample privacy and time to explore any topic with a patient. Granted there may be certain diagnoses where this would be less of an issue, but without developing a private and trusting relationship, the quality of the information and relationship is not the same.”

At its December 2003 meeting, the CCRMG voted 9-0 (with one abstention) against issuing initial approvals by telemedicine. Several members, including Mikuriya, were being investigated by the Medical Board of California (the complaints against them invariably coming from Law Enforcement Officers, not patients), and as Mikuriya put it, resignedly, “We can’t fight two battles at once.”

Hadorn expressed his disappointment:

“…We really cannot practice in knowing contravention of the reaffirmed judgment of my de facto peer group. I wouldn’t have a leg to stand on when the MBC came knocking… My feeling at this point is that, much as I hate to do it, we need to re-suspend our practice until such time as our protocol is deemed standard of care by our peers. We do not wish to practice (outside a study setting) without the endorsement of the California Cannabis Research Medical Group.”

Hadorn and Jackson then reconsidered and decided to continue issuing approvals by telemedicine without CCRMG support. They did so until 2005.

The paper by Hadorn and Jackson, “Telemedicine and Medical Cannabis Evaluations,” did not get published. And yet it truly is a landmark study. There’s no advantage to being too far ahead of the curve. —Fred Gardner