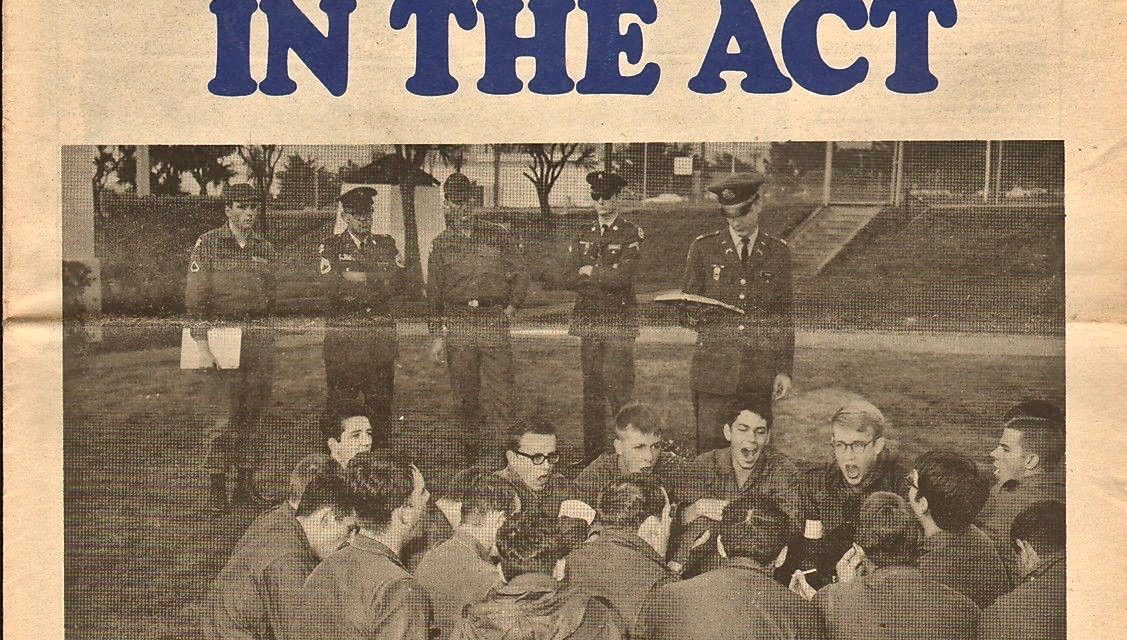

The event that came to be called “The Presidio Mutiny” was a non-violent sit-down in the yard by 27 prisoners to protest stockade conditions and the fatal shooting three days earlier of a fellow prisoner, Richard Bunch, who was obviously delusional and should have been discharged. At roll call on the morning of Monday, October 14, 1968, the 27 broke formation —Keith Mather was first— and sat down in a sunlit patch of the stockade yard. They sang the chorus of “We Shall Overcome,” which a few of them knew from having seen demonstrations on TV. Ricky Lee Dodd knew the chorus of “This Land is Your Land.” They chanted “Freedom.” They sang “America the Beautiful.”

The participants were all white, except Buddy Shaw, who was half Native American. The Black prisoners shared their grievances but figured that if they took part the punishment would be severe. Only five of the 27 had finished high school; their median educational level was 10th grade. Almost all were from small towns or working-class suburbs —Hayward, San Bruno. Most had enlisted to get out of trouble or to learn a trade, many having been misled by a recruiter’s pitch. Nobody dreamed that the new commanding general of the Sixth Army, Stanley Larsen, and the Army’s new Chief of Staff, Gen. William Westmoreland, might welcome a show trial to impress on US troops that protest within the ranks would not be tolerated in any form.

When the stockade commander, Captain Robert Lamont appeared with the Uniform Code of Military Justice in hand, Walter Pawlowski stood up and read the prisoners’ list of demands. Lamont watched him in silence. Pawlowski asked, “May we have a reply, Sir?” Lamont started to read the mutiny article from the UCMJ but was drowned out by a loud reprise of “We Shall Overcome.” The compound was surrounded by a “reactionary force” of 40 MPs in camo fatigues and gas masks, wielding outsize billy clubs. The mutiny article was read again over a loudspeaker and the men were given a direct order to return to their cell blocks.

At this point Randy Rowland stood up to say, “We can neither comply with nor disobey any order until our civilian counsel is present. We want Mr. Hallinan.” The group took up the chant, “We want Hallinan.” And then, for the sake of the rhyme, “We demand Hallinan!” A photographer from the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division circled the group taking pictures. They flashed the peace sign to signify their non-violent intent and yelled “Peace, brother!” to the MPs. At the ensuing court martials Terence Hallinan would represent 14 of the 27 men charged with mutiny —a capital offense. Army prosecutors contended that Rowland, his initial client, was the leader. They had more on Pawlowski, who read the grievances, and Mather, who was first to break ranks. But the two of them had escaped.

“There were two kinds of resisters inside the stockade, peacers and dopers,” Pawlowski explained when I met him and Mather in Vancouver, BC. “I guess ‘street people’ would be a better term than ‘dopers,’ since not all of us were into dope. There were only a few peacers. They were very well respected because everybody knew what a hard time they were giving the Army. But they weren’t really influential with the street people… Rowland, coming into the stockade on Saturday night, wasn’t going to convince anybody to do anything Monday morning. In fact, convincing people wasn’t Randy’s thing. He was always concerned about what other people wanted and needed. A really beautiful person —kind of what I imagine a primitive Christian to be like. You know, a real one.”

The stockade is at Fort Scott, a beautiful enclave in the Presidio’s northwest corner that overlooks the ocean and the bay, the Golden Gate Bridge, and the rolling hills of Marin County. Its two small buildings had been filling up all summer with AWOL GIs drawn to the “Summer of Love” and some, like Rowland, who decided at the last minute not to ship out from Oakland, the main embarkation point for Vietnam. There were 53,357 desertion cases in the Armed Services in fiscal 1968 and 155,536 AWOLs, the equivalent of 15 combat divisions. Someone was splitting from the Army every three minutes.

The Presidio stockade population doubled from about 60 in February to 120 in October. The overcrowding caused a food shortage. Very few discharges were being granted for psychiatric reasons. Suicide attempts were frequent. Men would slash their wrists or elbows, get stitched up at Letterman Hospital, and sent back to the stockade by psychiatrists who defined the self-destructive acts as mere suicide “gestures.” Ricky Lee Dodd, a well-liked prisoner, slashed his throat in May, got stitched up and then placed in segregation back in the stockade. In June Dodd tried again by slashing his wrists. He was heard gasping under his blankets and rushed back to Letterman where he was stitched up and returned again to segregation. There he unwound his bandages and using them and his bootlaces for a noose, hung himself from the wire mesh covering the ceiling. Rushed back to Letterman, he was pronounced dead on arrival. Doctors somehow got him breathing again and he was sent back to the stockade and once more sent to the grim “black box.”

Richard Bunch had asked a prisoner named Billy Hayes to recommend an “easy way” to commit suicide. Hayes, not taking the question too seriously, ran down some of the methods he had seen used: hanging, cutting your arms or throat, drinking lye, oven cleaner, or chrome polish. He jokingly added, “Tell a guard you’re gonna run away and he should shoot you.” Two days later Bunch heeded the advice. “How could I have known,” a grieving Hayes asked the other prisoners, who assured him the blame lay elsewhere.

Lindy Blake, one of three prisoner on the fatal work detail, recalled Bunch asking the guard, “’Would you shoot me if I ran?’ I heard him say something like ‘Aim for my head’ or ‘Better shoot to kill.’ I wasn’t paying too close attention… I heard the click of the shotgun being cocked and I turned to see the guard aim and fire, hitting Bunch in the small of the back. There was no command of ‘Halt’ given.” Another prisoner on the work detail described the hole in Bunch’s chest as “big as a grapefruit.”

When word of the killing got back to the stockade, according to Walter Pawlowski, “People stared for a while at Bunch’s bunk and then began breaking the iron rungs off the bunks to use as weapons. We broke windows, overturned bunks, threw things. A couple of people tried to get a fire going.” Sgt. Woodring appeared and a prisoner named Harrington asked “How come you killed Bunch?” Woodring threw him down the stairs and Harrington was put in segregation with a dislocated shoulder.

A prisoner named Reginald Bailey made a dye out of shoe polish. He and five others dyed their armbands black. (Stockade prisoners wear a strip of white cloth as an identifying stigma.) At a formation after the lunch that no one ate, Woodring and another sergeant ripped off the black armbands. Captain Lamont appeared in front of the formation with a manual in his hand. He had come from a conference with Lt. Colonel John Ford, the Presidio’s Provost Marshal, who had suggested that Lamont read Article 94 —the mutiny article of the UCMJ— to the prisoners: “Any person subject to this code who, with intent to usurp or override military authority refuses, in concert with any other person or persons, to obey orders or otherwise do his duty or creates any violence or disturbance is guilty of mutiny… A person who is found guilty of attempted mutiny, mutiny, sedition, or failure to suppress or report a mutiny or sedition shall be punished by death or such other punishment as a court-martial may direct.”

All Friday night men stayed up plotting, cursing, muttering. Woodring had gone on an isolate-the-leaders binge, putting Pawlowski, Mather, Dodd, and a tough biker named Frenchy Kight into cell block 4, and moving the nonviolent peacers Dounish, Jones, Martinez and Guthrie from building 1213 to 1212, where conditions were slightly less harsh. The move didn’t keep anyone incommunicado because all the upstairs locks had been broken and couriers crossed between the buildings. In each, men were staying up discussing what they could do.

Bunch had been in the stockade for three and a half weeks. He was slender, sandy-haired and small; Mike Marino thought he looked 15 years old. “He said he could walk through walls,” Ricky Stephens remembered. Roy Pulley saw him try it a few times. Bunch told Alan Rupert that he’d been a sergeant in Vietnam. Richard Duncan had stared as Bunch “sat on his bunk having a perfect two-way conversation —only he was talking for both people.” He filled a notebook with incoherent writing and drawings. He had originally gone AWOL from Fort Lewis. In late May he showed up at his home in Moraine, Ohio. His mother would recall, “He told me he had died twice and been reincarnated a a warlock —that’s a male witch, he said. And he had been in a flying saucer and talked to men from Mars and you couldn’t photograph him and he could walk through walls. I said, ‘Rusty, sit down and eat some supper.’ When he didn’t get better I called the VA hospital and they said it wasn’t their jurisdiction. ‘Don’t bring him in here.’ We didn’t have an Army base nearby so I called Wright Patterson Air Force Base. They said the same thing. Later I found out that these hospitals called the police.”

Although Capt. Lamont was the stockade commander in the months leading up to the “mutiny,” the effective authority was Sgt. Thomas Woodring, a burly Korean War vet who had spent eight years as an LA policeman, then re-enlisted in 1963. The prisoners considered him sadistic. According to an affidavit by prisoner Roy Pulley, Woodring had liquor on his breath the day “he knocked me down and sat on my stomach, pinning my right arm with his knee. Then he grabbed my wrist with one hand while with the other he took hold of my fingers. Then, slowly and methodically, he twisted my fingers until one of them was broken.”

Woodring deemed the Black prisoners a “clique” that had to be broken up. Prisoner Joe Stephens recalls, “I went up to him and asked, ‘How can you keep people separated when you’ve got 150 in a place built for 75? But they tried, all right. Whenever there got to be more than 10, 12 blacks, they’d ship some out to Fort Lewis. It never failed.”

Randy Rowland didn’t arrive at the stockade until Saturday night, October 12. He was a medic whose conscientious objector application had been rejected. He had been due to ship out to Vietnam from Oakland in late June 1968. In the Bay Area he met George Dounis and Chuck Jones, two of the nine service members who were planning to seek sanctuary in a San Francisco church. “I decided to make my personal act a public one, to help the peace movement,” Rowland would later tell a non-plussed Army court. “But I wasn’t sure of how to do it. I sort of shopped around for the best way.” He was working on a new CO application and wanted to consult a lawyer. Someone recommended Terence Hallinan.

“Hallinan’s advice,” Rowland recalled when we talked after Terence’s death in January of this year, “was ‘Stay AWOL for 30 days, then turn yourself in. You’ll be charged with AWOL, and I’ll help you do a more proper CO application.’ So that was the plan. That’s why I didn’t report to Oakland. When I went back to see him after 30 days he suggested I turn myself in at the end of the big peace march that was coming up with GIs and vets in the leadership. He said, ‘I have these other guys who are going to turn themselves in. You’ll be accomplishing your personal mission and you’ll be helping the movement.’ The ‘9 for Peace’ had happened and made an impact. I said ‘Okay, sure.’”

So Rowland marched from Golden Gate Park to the Civic Center with a contingent of active-duty servicemen and women and veterans in the front ranks and 15,000 civilian supporters on Saturday, October 12, while intelligence agents from all the services took their pictures. (The Army videographer would also shoot the sit-down at the stockade on Monday.) Every young man with short hair was asked to produce an ID and a pass by MPs. Mandatory inspections had been scheduled in many companies at the Presidio, Travis Air Force Base, and the Treasure Island Naval Station. Men known to have antiwar views were denied passes —as was Private First Class Richard Lee Gentile, a Vietnam combat vet stationed at the Presidio. Gentile wrote a note to his company commander explaining why he felt entitled to march, then took off. When he returned to the Presidio Saturday night, he was thrown into the stockade —inordinate punishment for a man reporting back voluntarily after briefly breaking a restriction. A native of Virginia whose arm was tattooed with the Confederate flag, Gentile would join the circle singing “We Shall Overcome” on Monday.

During the march, word spread that a prisoner had been killed at the stockade and some kind of riot had been put down the day before. Rowland recalled in our recent conversation: “So Hallinan told me, ‘After you turn yourself in, they’ll throw you in the stockade. I’ll come visit you as your lawyer on Sunday. Find out what’s going on and give me a report. And see if the guys want to take it to a higher level, like have a sit-down protest or something.”

I asked Rowland to repeat himself. “It was Hallinan’s idea?”

“That was Terry Hallinan’s idea,” he confirmed. “And I was the guy. So I went and did the march and gave a speech at the end of it, stepped over the line into the Presidio, and they took me into custody. But they didn’t put me in the stockade. So now it’s Saturday evening and I’m in SPD instead of the stockade. So I just walked down into the orderly room and there’s an old sergeant down there reading Playboy. And I walked up to him and said “I refuse to sweep this room on grounds of conscience.” Old sarge handcuffed me to a little folding chair and 30 minutes later I was in the stockade.

“I walked into a cell block and said, ‘Okay, the movement sent me here to see if we can organize something about this guy who got shot.’ And everybody said, “Cool!” They’d had a riot on Friday and were trying to figure out what to do. Keith Mather was already in there and I linked up with him right away. I was a stranger, but Keith had already gained all kinds of respect.”

Randy Rowland was one of many people —maybe millions— who spoke about the amorphous “movement” of the ’60s as if it was an organized political party. “Imagine,” he reflected in January, 2020, “Going into a prison and saying ‘The movement sent me.’”

Rowland told the prisoners about Hallinan’s idea for “sit-down protest,” and that he would be visiting the stockade the next morning if anyone else wanted to consult him. Also, that Hallinan would not charge anyone who couldn’t afford to pay. (Soldiers facing court martial are assigned a defense attorney by the Army and can also hire civilian lawyers.) The sit-down was seen as an alternative to some of the violent tactics being considered, like taking guards hostage until certain demands were met, or just tearing the place apart..

For more than 50 years Rowland did not reveal Hallinan’s true role, he said, “because it would have gotten him in trouble. But it can’t hurt him now. Hallinan was so cool because he was reaching behind the prison walls and organizing the prisoners to take it to a higher level. And he was right! They wanted to take it to a higher level. They wanted to have an impact. They wanted to fight back. They wanted to do something and he knew what was possible.”

When Hallinan visited Rowland on Sunday morning in a small, ground-floor office, many other prisoners also tried to see him. “You felt a civilian lawyer was the key to getting out, a miracle worker,” said Pawlowski, who was among them. A few days earlier all the prisoners would have been able to consult him, but on the day of the sit-downthe Presidio judge advocate had instituted rules that sharply restricted access to counsel. A civilian attorney now had to have a letter in hand from a prisoner specifically requesting his services. The lawyer had to give the stockade 24 hours advance notice of a visit. And since prisoners had to address an attorney by name, the new rules blocked them from obtaining counsel simply by writing the office of a civil liberties group such as the War Resisters League.

Hallinan spent two hours talking informally with Rowland and some of the prisoners before he was escorted out by MPs. They handed him Bunch’s incoherent notes and shared their grievances. That night there would be a meeting in cell block 4 —a 10-by-20-foot room with five double bunks— to plan their collective response.

PS: I wrote a book about the Presidio Mutiny case –The Unlawful Concert– that was published by Viking in 1970 and favorably favorably reviewed by John Leonard in the New York Times. In 2005 it was reissued by Gryphon and dissed in an introduction by Alan Dershowitz, who made the odd assertion that “There were many pivotal events that contributed to ending the Vietnam war, but perhaps none was more important than the so-called Presidio mutiny and the subsequent court martial of the mutineers.” Dershowitz objected to the idea that soldiers should have a say in whether the war was worth fighting. He obviously hadn’t read the whole book. If he had, he would have noted that one of the captains assigned to the defense was Brendan V. Sullivan, Jr., who had become famous as Oliver North’s lawyer during the Iran-Contra investigation.