On September 5, 2002, US government agents raided the garden cultivated by members of the Wo/Men’s Alliance for Medical Marijuana and arresteded WAMM leader Valerie Corral and her husband Mike. Until that day it was hoped by many activists that the DEA would be going after “bad actors,” not the most righteous growers and distributors.

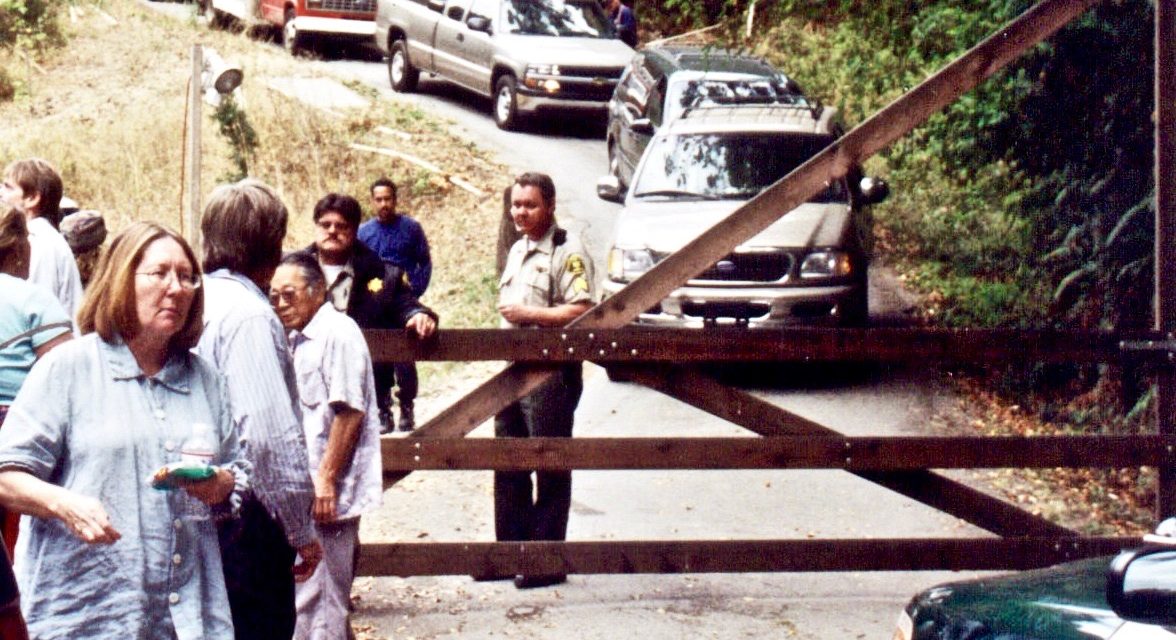

As word spread through the community, distraught WAMM members headed for the Corrals’ land, which is at the end of a mile-long driveway on a steep hillside about 15 miles north of Santa Cruz. They padlocked a gate through which the raiders would have to pass on their way out, and parked two vehicles across the driveway for good measure. The DEA agents called the Santa Cruz County Sheriff to facilitate their exit. Two deputies arrived in the late morning and were able to reach Valerie at the Federal Courthouse in San Jose, where she was told that she and Mike would be released immediately if she’d instruct her friends to let the raiders depart. She did so, and within five minutes the road was cleared and the government convoy —five big, tan SUVs and two 13’ U-Haul trucks— rolled past the WAMM members, who cried “Shame on you!” and “Terrorists!” The drivers averted their eyes and the rest of the raiders hid in the back of the vehicles —except for one young Caucagent in combat gear and diamond-shaped shades who gloated malevolently through a dark-tinted rear window.

The WAMMers then made it up the hill to survey the destruction of their garden(s). All that remained were robust stumps, two to four inches in diameter, and some branches and leaves scattered on the ground. People wept and muttered “Jesus,” and “Why?” A middle-aged man who walked with two canes (a surgeon having nicked his spine) looked at a stump and said, “I trimmed that plant on Tuesday.” What wonderful therapy it must have been to come to this lovely hillside, with a glimpse of the Pacific in the distance, and work for a while in the sun with people you could relate to, feeding and caring for plants that would in turn take care of you, and enjoying the hospitality and encouragement of the Corrals, whose lives, it is no exaggeration to say, have been devoted to helping people whose days are numbered.

WAMM is not about money at all. Meetings are held in downtown Santa Cruz on Tuesday evenings, at which time cannabis is given to members according to their stated need, usually about 7-10 grams, more in some cases. Some members bring baked goods and butter-based extracts and tinctures to share. The Corrals live very modestly on the hillside they’ve been clearing and planting for 16 years; donations from a few well-wishers enable them to devote their time and energy to WAMM.

“This is the case we’ve been waiting for,” says Dale Gieringer of California NORML. “The Corrals can argue that the feds had no jurisdiction because WAMM consists of individual patients growing for their personal use within California.” WAMM’s support in the community is very strong. The Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors has already passed a resolution denouncing the raid, and WAMM has been invited to do its Tuesday Sept. 17 distribution of marijuana (there’s still some from last year’s crop) in city council chambers. A rally to demonstrate public support has been called for that afternoon.

As we got to press on Sept. 10, the Corrals have not been charged (nor have Alan MacFarlane of Santa Rosa or Eddy Lepp of Clear Lake, whose gardens were uprooted in recent weeks). The feds realize that punishment by confiscation is severe punishment indeed. Their message to patients and caregivers in California is: “We’ll destroy your year’s work, we’ll take away your precious medicine, we’ll keep you in endless uncertainty about what you can grow in your garden… But if you have solid support in the community, we won’t let a jury of your peers affirm your rights.”

It became apparent during the WAMM raid that a split within law enforcement is beginning to widen. The two Santa Cruz sheriff’s deputies who came to resolve the driveway stand-off did not exude admiration for the just-following-orders cruelty of the DEA agents. The locals know very well that WAMM is a caregiving enterprise, that its members have authentic, serious needs; they’ve seen Valerie in action at the city-government level; they did not like being a party to this raid, which the feds decided on without consulting their boss, Sheriff Mark Tracy, or even District Attorney Kate Canlis.

If the crackdown on medical marijuana continues, the split will run through every agency —local, state and federal— and through many an individual officer’s conscience. Valerie reports that her forthright defense of WAMM “got through” to at least half of the 20-or-more federal agents (all male!) who took part in the bust.

The knock on the door came at 6: 50 a.m. She’d been up till 3 a.m. talking with three co-workers about a recent spate of deaths (five in two weeks) that had taxed their resources as caregivers. One of the overnight guests was paralyzed from post-polio syndrome; another had AIDS. “Get on the floor!,” was the order. “I want to see a search warrant,” said Val, who is five feet tall and 50 years old, and has epilepsy. She was thrown to the floor and then handcuffed. Her friend Suzanne was ordered to get on the floor. “Can’t you see those braces?” said Valerie. “Don’t you see she’s on a breathing machine? What would your mother say if she knew you were talking this way to a sick woman?”

A younger woman was handcuffed bare-chested. “I guess they liked her breasts,” says Valerie.

The officer in charge of the raid was named Patrick Kelly. Valerie went into an Irish brogue for him: “Ah, Patrick Kelly! I’ve just been reading James Joyce and I say ‘Shame on you, Patrick Kelly, you’ve done a disservice! Seven hundred years of occupation and oppression, and you turn into an agent of occupation and oppression in my house!’”

Mike made a comment about all the automatic weaponry trained on him. “You’re a martial artist,” he was reminded. “Hey, I’m a martial artist, too!” said Val.

An agent waved towards the land and said, “Look at how you live,” as if the Corrals enjoyed a life of privilege based on ill-gotten gains. “What do you know about how we live and how we got this land?” Valerie shot back. (The parcel is in an extremely steep canyon, not exactly prime.) “Mike’s father was a farmworker, my grandfather had a fishing boat, what do you know about us? Our work speaks for itself.”

“Look at what you drive, a $40,000 car.” This reference was to Mike’s 1997 Audi wagon.

“What do you know about that? We were broadsided on Highway 1! I drive a ’63 Rambler! All you know are some lies promulgated by your bosses to make you hate us.”

(Mike got a $10,000 payment from the accident and bought the Audi for $14,000.)

To an agent of Chinese descent Val said, “Your parents who came from China, didn’t they tell you about government oppression? Can’t you recognize government oppression?” He said she was insulting his family. She was polite but didn’t back down. “I’m not insulting your family at all. You insulted me, coming into my house and pointing guns at me and having me thrown on the floor.”

Valerie and Mike succeeded in getting their friends released (in one case by taking her blood pressure and showing the ominous results to Kelly, who realized that a citizen suffering a stroke while in his custody might not be a good thing). Val pleaded for the plants, explaining how WAMM works, and what marijuana does for people with AIDS and cancer and seizure disorders, citing California law and scientific literature… “Arrest us but leave the plants, please…” No dice. Federal law.

“When you get into bed tonight,” Val told the man who had thrown her to the floor, “I’m going to be with you. And you’re going to think about me and what you did. And I’m going to stay with you all your life. I’m going to be with you whenever you’re suffering. I’m going to be with you on your deathbed. You’re going to think about me, because there’s no way out of life without suffering.”

Finally Patrick Kelly snapped, “Get these two out of here right now,” and the Corrals were taken by van to the federal courthouse in San Jose, and uniformed agents of the mighty United States government chainsawed the cannabis plants in their gardens. The feds say they took 167 plants —which comes to less than one per WAMM member.

Recalling the episode a few days later, Valerie says that after the initial confrontation the mood began changing, and before it was over, many of the men had subtly conveyed to her that they were ambivalent about what they’d been ordered to do. One agent told her that he was thinking about looking for another line of work. Their average age was 25 to 28, Val estimates.

For more movement history check out The O’Shaughnessy’s Reader at www.beyondthc.com