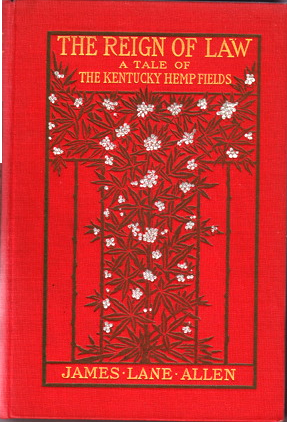

The new O’Shaughnessy’s includes an excerpt from a novel published in 1900 by Macmillan, “The Reign of Law: a tale of the Kentucky Hemp Fields,” by James Lane Allen. If published nowadays it would probably be shelved among the romance novels. The heroine, Gabriella, comes from a wealthy family (even though they’ve lost their slaves). She is a devout young woman, takes the Bible literally. The hero, David, is the son of a devout hemp farmer. David goes off to college and learns about evolution. He comes home, gets expelled from the church founded by his great grandfather, and feels the wrath of his father and the disappointment of Gabriella. He gets pneumonia and is near death. He pulls through. He decides to go back to college and study the physical sciences. Gabriella, though her faith in Christianity is unwavering, will go with him.

The first chapter, “Hemp,” is a florid paean to its subject. Some excerpts follow:

The Anglo-Saxon farmers had scarce conquered foothold, stronghold, freehold in the Western wilderness before they became sowers of hemp—with remembrance of Virginia, with remembrance of dear ancestral Britain…

Hemp in Kentucky in 1782—early landmark in the history of the soil, of the people. Cultivated first for the needs of cabin and clearing solely; for twine and rope, towel and table, sheet and shirt. By and by not for cabin and clearing only; not for tow-homespun, fur-clad Kentucky alone. To the north had begun the building of ships, American ships for American commerce, for American arms, for a nation which Nature had herself created and had distinguished as a sea-faring race. To the south had begun the raising of cotton. As the great period of shipbuilding went on—greatest during the twenty years or more ending in 1860; as the great period of cotton-raising and cotton-baling went on—never so great before as that in that same year—the two parts of the nation looked equally to the one border plateau lying between them, to several counties of Kentucky, for most of the nation’s hemp.

It was in those days of the North that the CONSTITUTION was rigged with Russian hemp on one side, with American hemp on the other, for a patriotic test of the superiority of home-grown, home-prepared fibre; and thanks to the latter, before those days ended with the outbreak of the Civil War, the country had become second to Great Britain alone in her ocean craft, and but little behind that mistress of the seas. So that in response to this double demand for hemp on the American ship and hemp on the southern plantation, at the close of that period of national history on land and sea, from those few counties of Kentucky, in the year 1859, were taken well-nigh forty thousand tons of the well-cleaned bast.

What history it wrought in those years, directly for the republic, indirectly for the world! What ineffaceable marks it left on Kentucky itself, land, land-owners! To make way for it, a forest the like of which no human eye will ever see again was felled; and with the forest went its pastures, its waters. The roads of Kentucky, those long limestone turnpikes connecting the towns and villages with the farms—they were early made necessary by the hauling of the hemp. For the sake of it slaves were perpetually being trained, hired, bartered; lands perpetually rented and sold; fortunes made or lost.

The advancing price of farms, the westward movement of poor families and consequent dispersion of the Kentuckians over cheaper territory, whither they carried the same passion for the cultivation of the same plant,—thus making Missouri the second hemp-producing state in the Union,—the regulation of the hours in the Kentucky cabin, in the house, at the rope-walk, in the factory,—what phase of life went unaffected by the pursuit and fascination of it. Thought, care, hope of the farmer oftentimes throughout the entire year!