By Tod Mikuriya, MD, in O’Shaughnessy’s, Summer 2003

In the fall of 1871 the British government in India decided to investigate “the deleterious effects alleged to be produced by the abuse of ganja.”

Inquiries were sent to regional governments, some of which, in turn, obtained reports from local insane asylums. Responses from a dozen parts of the country were summarized in the “Supplement to the Gazette of India” for Dec. 27, 1873 in a four-and-a-half page report.

This 1873 report can be seen as a predecessor to the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report of 1893-94, a massive ethnographic, social, and economic study by British proprietors who were seeking to answer a basic question of cost/benefit analysis.1, 2

The goal of the brief 1873 survey was the same as that of its eight-volume successor: to determine whether the use of cannabis by certain groups was associated with mental disorders. In both reports the collection and review of information varies greatly in quality and quantity, reflecting the biases, competence, and knowledge of the reporting officials. Both describe regulatory and taxation schemes based on performance and practicality that might provide models for contempory cannabis legalization.

In fact, it was in contemplating models for the regulation and distribution of medicinal cannabis in California that I recently consulted the IHDC Report and came across a citation to the 1873 document, with which I was unfamiliar.

A copy was provided by the Indian Office Records Library and is reprinted here in full.

The overall conclusion, as stated in paragraph 3, hardly seems out of date: “On some points the local officers are almost unanimous, yet on others there is wide disagreement. On the whole, the general opinion seems to be that the evil effects of ganja have been exaggerated.”

Only two of the local governments advocated prohibition. Most of the negative input came from insane-asylum administrators.

More text follows the graphics. Tod saw the erasure of history as the ultimate prohibition. A treasure trove awaits the scholar who explores the Mikuriya archive at the National Library of Medicine. Sorry about the quality of the scan. —FG

Regional Responses

Madras (4): “the evil effects of the use of ganja have not assumed such proportions as to necessitate legilsation.”

Mysore (5): Sale of cannabis by “vendors specially licensed” was recommended. “Its influence in inciting to crime is stated to be very slight. It is however reported that out of a total of 280 admissions to the Lunatic Asylum in Bangalore… ganja was assigned as the cause of insanity of 82 persons.”

This is the most exaggerated connection between cannabis and insanity in the Report.

Berar (6): “The abuse of these drugs is not so great… as to necessitate any special measures.” One official describes cannabis as a morale booster for criminals (but not an efficiency booster) and states that habitual use “undermines and destroys the constitution.”

Central Provinces (7): The Nagpur asylum attributes 61 cases of lunacy to cannabis (out of 317). However, the Superintendent of the asylum at Jubbulpore doesn’t view cannabis use as causal. “(He) states that out of 120 lunatics at present confined, 37 indulged in ganja smoking. And he deduces from certain statistics which he has collected that there is only one lunatic from all causes for every three hundred ganja-consumers.”

The Chief Commissioner’s recommendation was “that the cultivation of ganja without a license be absolutely prohibited, and that the issue of licenses be restricted to places where the cultivation and out-turn could be checked by the ordinary revenue establishments.”

Bombay (8): “The government, while desiring that ganja and bhang should be treated as other intoxicating drugs or spirits and the present restrictions on their sale maintained, consider it unnecessary to take measures for the limitation of suppression of the hemp plant.”

Punjab (9): “the amount of crime that can be traced to the use of the preparations of hemp is exceedingly small, so small as to make it altogether impolitic and unnecessary to attempt to restrict the sale of the products of the plant by law.”

However, the Delhi Lunatic Asylum attributed between 11.9% and 20.6% of its cases to the use of hemp preparations.

The lieutenant governor literally advised a harm-reduction approach: “If people were prohibited from using the preparations of hemp and opium, they would in all probability have recourse to some other stimulant, such as alcohol, the crime resulting from the abuse of which would be much greater than that resulting from the abuse of those drugs.”

Northwestern Provinces (10): “The lieutenant governor believes that…even the returns of the lunatic asylums are based on hearsay reports and have no scientific value.

“It appears to His Honor that if the effects of the use of ganja were nearly as bad as is sometimes supposed, either as inciting to crime or as injuring health, such a wide enquiry would have resulted in a more general and decided consesus of opinion and in the production of numerous facts bearing out that opinion. Accordingly His Honor does not recommend the adoption of any special meaures to limit or stop the production of the plant. As it grows freely in the country lying along the foot of the Himalayas, and can be cultivated in every moist and lowlying tract, to prevent its production would, His Honor apprehends, be almost impossible.”

The same points could be made about contemporary cannabis prohibition in the U.S.

Oudh (11): “The evil effects of the use of hemp have been exaggerated… there is nothing to show that bhang, if used at all, must be used immoderately, or that if used in moderation, it has mischievous consequences.”

The Chief Commissioner (another harm-reductionist) “believes that any interference with the cultivation and use of hemp and its preparations, is not called for on moral grounds and that arbitrarily to stop their use would merely drive the people to the use of still more deleterious drugs.”

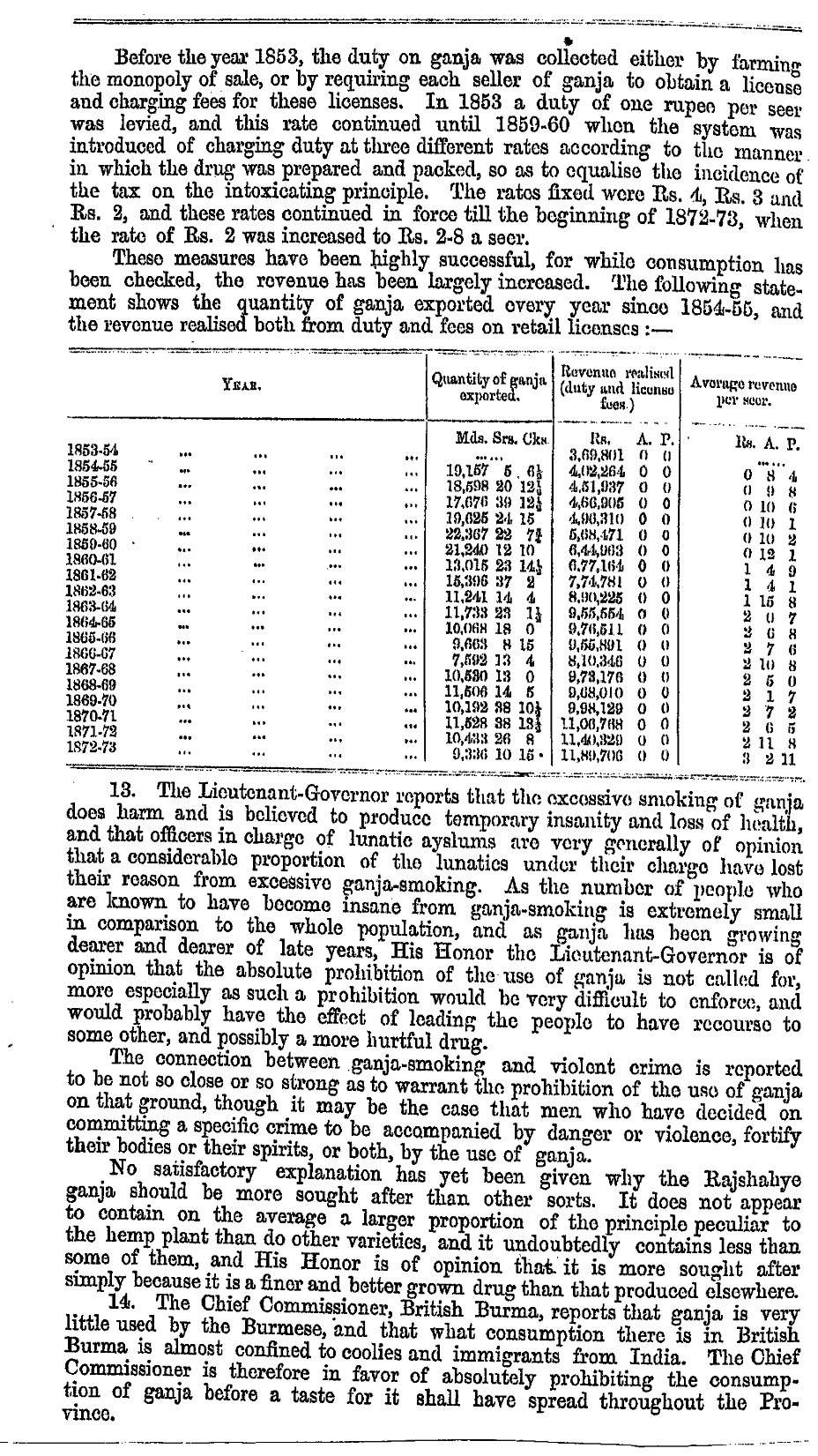

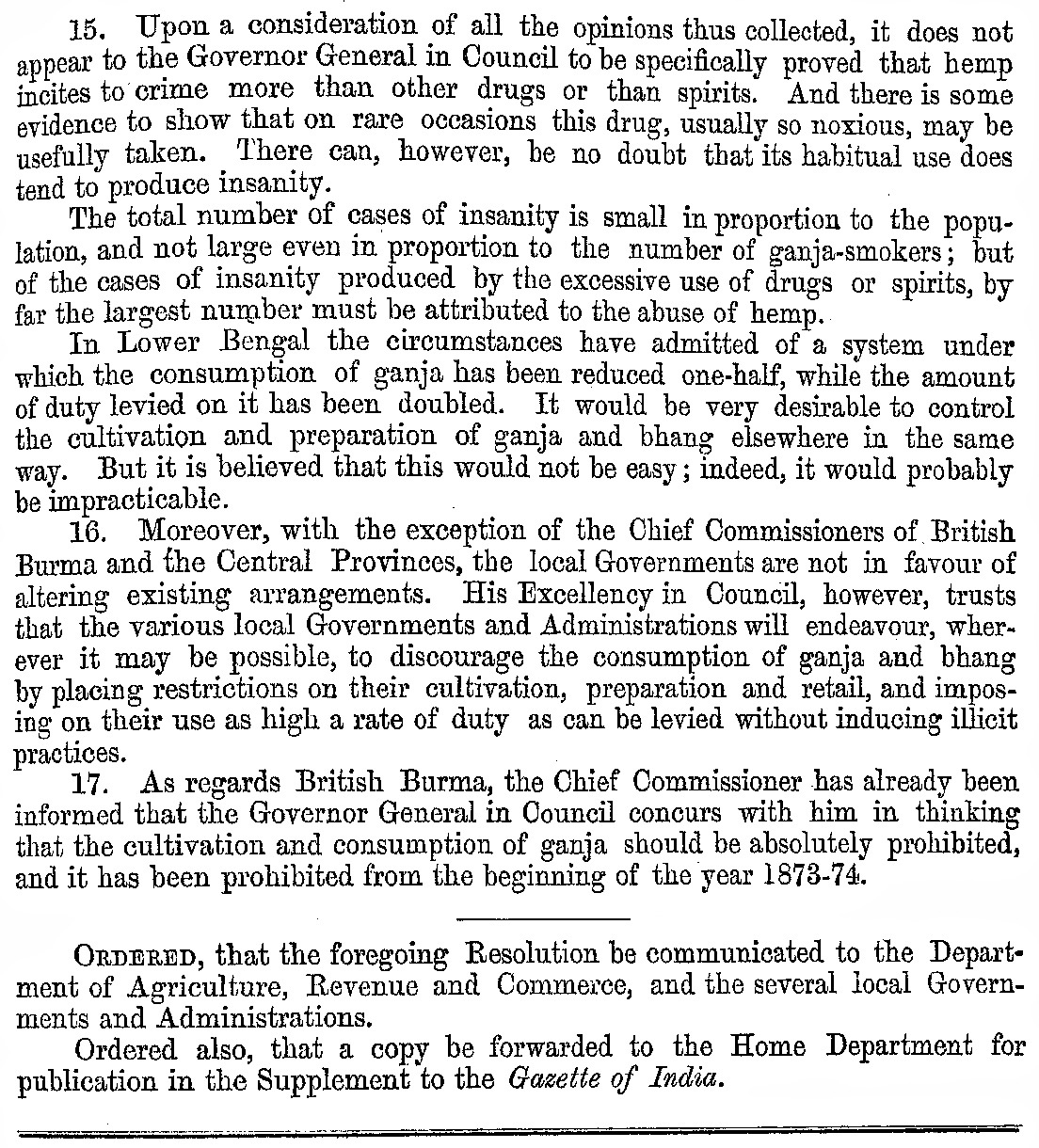

Bengal (12-13) describes a system for taxing farmers on the basis of how much “intoxicating principle” a given quanity of processed cannabis contained. “These measures have been highly successful, for while consumption has been checked, the revenue has been largely increased.”

“especially as such a prohibition would be very difficult to enforce…”

Although some asylums report cannabis-induced insanity, “the number of people who are known to have become insane from ganja smoking is extremely small in comparison to the whole population… The absolute prohibition of the use of ganja is not called for, more especially as such a prohibition would be very difficult to enforce, and would probably have the effect of leading the people to have recourse to some other, and possibly a more hurtful drug.”

Bengal officials had been asked (2) to report “any evidence to show that Bengal ganja grown in the district of Rajshahye different from, and was more deleterious than, the ganja produced in other parts of India.”

The response: “No satisfactory explanation has yet been given why the Rajshahye ganja should be more sought after than other sorts. It does not appear to contain on the average a larger proportion of the principle peculiar to the hemp plant than do other varieties, and it undoubtedly contains less than some of them.”

The Rajshahye success factor may never be known.

British Burma (14): “…What consumption there is in British Burma is almost confined to coolies and immigrants from India. The Chief Commissioner is therefore in favor of absolutely prohibiting the consumption of ganja before a taste for it shall have spread through the Province.”

The Bottom Line (15-16)

Only the governors of British Burma and the Central Provinces sought prohibition. The other provincial administrators were advised by His Excellency to “endeavour, where it may be possible, to discourage the consumption of ganja and bhang by placing restrictions on their cultivation, preparation, and retail, and imposing on their use as high a rate of duty as can be levied without inducing illicit practices.”

As noted, this survey from another time and culture is curiously modern in many ways. Controversy remains regarding the relationship between mental disorder and cannabis use. In California we now have the opportunity to conduct clinical studies that will help determine risks and benefits of long-term cannabis use.