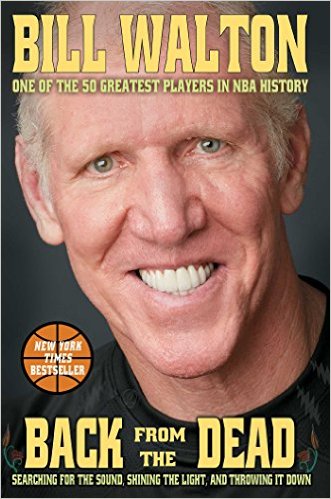

One of the 50 greatest basketball players of all time has written one of the 50 greatest autobiographies of our time! “Back From the Dead” by Bill Walton (Simon & Schuster 2016, 327 pages, $27) describes some of the highest highs a man can experience in an ebullient style that lifts you right into his joy. Some deep lows are described, too, involving physical pain. Walton has endured 37 orthopedic surgeries.

If you’ve ever heard him doing color commentary on a basketball broadcast, you know the tone of reverence that Walton reserves for John Wooden, his coach at UCLA, and you’ve heard him quote Wooden’s maxims, like “Failing to prepare is preparing to fail,” and “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far you need a team.” Words to live by, for sure!

Walton’s admiration for Wooden is amplified in “Back from the Dead,” and another side of their relationship is revealed. During the 1973-74 season —Walton’s senior year— the tension between the coach’s straightness and the star center’s hippie worldview ceased to be good-humored. Walton doesn’t come out and say that Wooden’s anti-marijuana prejudice undermined the Bruins that season —in which their astounding winning 88-game winning streak ended and they fell short of the NCAA championship. But if you connect the dots in “Back From the Dead,” that’s the obvious conclusion.

Walton grew up in La Mesa a suburb of sunny San Diego. His parents were not into sports, though their children won big in the genetic lottery. Bill’s mother was the town librarian who made room for reading and conversation in the home by not having a TV. His father, who had fought in World War 2, was a social worker, adult educator and music teacher who could play any instrument.

At Blessed Sacrament elementary school Bill got a solid education but, he writes, “the nuns somehow had the misguided opinion that suffering, deprivation, austerity and repentance were the dominant themes by which to lead one’s life. That is not my idea of the world as it could be. I opted early on to have fun in this lifetime.”

Being on a winning basketball team was maximum fun. Bill’s high school team, Helix, won its last 16 games when he was a junior and went undefeated when he was a senior. He was skilled, hard-working, friendly, and almost seven feet tall.

Walton entered UCLA in 1970 with two other high school superstars: Greg Lee and Keith Wilkes (who would change his first name to Jamaal). Walton writes:

“Greg was a 6’5” guard who had grown up around UCLA sports. His dad, Lonnie, had played on the last pre-Wooden UCLA team, coached Greg at Reseda, and also managed all the ushers at Paulie Pavilion and the LA Coliseum, so Greg had been at every UCLA sporting event from his earliest conscious moments. He was a UCLA ballboy, valedictorian of every school he ever attended, and a superstar basketball player in high school —a two-time LA City Player of the Year. He worked summers as a counselor at Wooden’s basketball camps and it was the natural progression and order in life that Greg would become UCLA’s next great playmaking guard. He was virtually a son to Coach Wooden.”

Walton first met Lee and Wilkes when they was high school seniors invited to Stanford on a recruiting trip.

“We finally found ourselves together and alone… Instantly it was clear that Greg, Jamal and I were thinking the same thing: Let’s forget about all this nonsense and just make a deal right here and now that we’ll all go to UCLA together.”

Walton arranged to room with Lee.

“Though a freshman like me, Greg was already in his second UCLA quarter that September, having graduated from high school in February… so he was way ahead of us in experiencing all the wonders of life in Westwood. Greg was on campus when the strike and riots unfolded after Kent State and Jackson State… Our room was the same one that Kareem and Lucius Allen lived in when they were freshmen in 1966. It had the special extra-long and wide bed that had been brought in for Kareem.”

Walton’s first varsity season was ’71-72. (Back then freshmen were not eligible.) The team went 26-0 and beat Florida State in the NCAA finals. Two months later Walton was busted with 51 other students for taking part in an action aimed at shutting down the campus after “Nixon ordered a new and massive expansion of the Vietnam War, with naval blockades, the mining of harbors, and an enormous aerial bombing rain of terror.”

University lawyers negotiated the students’ release from a San Fernando Valley jail “after a few unpleasant and boring hours.” John Wooden drove out to the jail to drive Walton back to campus. As reported in Back From the Dead:

“Coach was not happy, to say the least. And he was in my face in a most determined fashion, unlike anything I had ever seen or witnessed before. And he went on and on about how I had gone TOO FAR THIS TIME. And that I had let EVERYBODY down. Him, his family. My family. UCLA and its family, The NCAA and its family. And basically anybody he could think of, which pretty much …

“What was I to say? I was guilty —of wanting PEACE NOW!

“…Finally I turned to him and said, ‘Look, you can say what you want, but it’s my friends and classmates who are coming home in body bags and wheelchairs. And we’re not going to take it anymore. We have to top this craziness. AND WE’RE GOING TO DO IT NOW!’

“Coach was taken aback and his voice suddenly changed… He started up again, in a more somber tone, about how he didn’t like the war, either, but that I was going about the whole thing in the wrong way… Then he started talking about how to reach goals and that in this case the best way to get my point across would be by writing letters of disagreement to the people in charge.”

Walton is appalled by the weakness of the suggested tactic. He goes straight to Wooden’s office and a secretary provides him with “some of the finest and cleanest-looking UCLA/John Wooden/NCAA Championship Basketball stationery you can possibly imagine.”

Back in his room. Walton “scripted a letter to Nixon on Coach’s UCLA stationery. I outlined all of Nixon’s crimes against humanity, then demanded an immediate end to the war and the return home of all our troops. Then I demanded his immediate resignation as our president, and I thanked him in advance for his cooperation.”

His teammates had been at the rallies on campus but not arrested. Walton writes:

“They were all very concerned. Bill, what did Coach say? What did he do? What’s going to happen?

“I told them everything was cool, that Coach had been very nice (I lied), and that he told me that instead of going to all these rallies and getting arrested and all, I should instead write letters. And I had written one.

“They were all excited and so I showed them my beautiful letter, on Coach’s stationery. They got all fired up, and as they were reading this heartfelt manifesto of freedom and peace, they asked if they could sign it, too. And they did. In big, bold, brave script.”

Walton then called on Wooden in his office to say that he “had taken his advice and had, indeed, written a letter. And that I hoped he would sign it.”

Wooden reads the letter and “the blood started to drain, his extremities turning white, and his calm, poised demeanor changed to uncertainty and boiling rage. I could see and feel that he want to tear the thing to shreds.”

Wooden says quietly that he can’t sign the letter and he hopes Walton won’t send it. Walton writes:

“With a big, joyous grin I told him ‘Coach, you told me to write letters! And I did. I always do exactly what you tell me!’

“Slowly and sadly he handed me back the letter, in perfect condition. I mailed it that day. And sure enough, Nixon resigned, although not soon enough, as the dead and broken bodies kept piling up.”

The Curse of the Selfish Point Guard

UCLA went undefeated in the 1972-73 season and beat Memphis State (led by Larry Kenon) in the finals. Greg Lee had 14 assists.

That summer Walton took classes at Sonoma State and biked all around Marin and Sonoma Counties. (Biking has always been one of his great loves.) One afternoon he was stung by a bee, went into anaphylactic shock, and was rushed by ambulance to a hospital in Santa Rosa. The paramedics had the good sense to phone a physician en route to give him an epinephrine shot and Benadryl in time to save his life. He returned to UCLA in great shape.

For the 1973-‘74 season Dave Meyers and Marques Johnson joined the varsity. “On the first day of practice,” Walton writes, “Coach told me that my hair was long and that I hadn’t shaved that day… He basically threw me out of practice.” Walton jumped on his bike, raced into Westwood for a shave and a hair cut, and in the end missed only three minutes of the drills. What he calls “the great unravelling” began at a practice soon thereafter:

“I was out on the court early warming up by myself when I noticed Coach walking with a mission across the court. Now, Coach was always fierce, but on this day he seemed more determined than usual as he made a straight line for Greg, who was also warming up alone but in the far corner from where I was.

“As I went about my business, I could not help but notice their animated conversation, which seemed unusually contentious, more than a simple how are things going, and how are you going to get the ball to Bill and Jamal today?

“That conversation ended rather abruptly and seemingly not well. Coach then made his way directly to me in the at the opposite corner of Pauley.

“When he got to me, he started right in. ‘Bill, it has come to my attention that you have been smoking marijuana.’

“Caught completely off guard, and totally surprised, I did everything I could to keep a straight face. In as composed, serious, and sincere a tone and manner as I could muster under the circumstances, I solemnly replied, ‘Coach, I have no idea what you’re talking about.’

“He took a deep breath and said ‘Good.’

“Then he turned on his heel and went back to getting practice started —right away.

“A bit later, in our first quiet moment together, I asked Greg what he and Coach had been talking about before practice.

“Greg indicated a similar line of questioning as I had experienced.

“Whatever Greg’s answers to Coach were that day, things were never the same again…

“Almost immediately our regular lineup, rotation, and style changed. Greg’s selflessness and remarkable ability to deliver the ball flawlessly in the most efficient offense in the history of the sport would no longer be the key ingredient to our unbeatable success. In his place we found Tommy Curtis.

“When you look at all that has gone wrong in basketball today, with little punk guards dribbling incessantly, aimlessly and without purpose other than to draw attention to themselves and promote some ridiculous individual culture of idiocy, selfishness, and greed, and where the most beautiful game in the world grinds to a halt while nine guys watch and wait for one guy who is dribbling for no reason other than to show off, then you have witnessed the madness and all consuming disease of conceit that defined Tommy Curtis.”

The team had Walton, Wilkes, Dave Meyers, Marques Johnson, Richard Washington and Ralph Drollinger… “And now with Tommy Curtis, none of us could ever get the ball when and where we needed it, if we could get it at all.”

Walton visited Wooden’s office repeatedly, lobbying for Greg Lee to get his job back. “We were all so used to getting the ball in perfect rhythm, at the instant we were open. And now we found ourselves waiting, waiting, waiting —endlessly, while Curtis kept dribbling for no apparent good reason.”

There was one game in January ’74, when “for the first time ever at UCLA, Greg, who had not lost a game as our starting playmaker/ball-handler/leader for the past three years, never even got in the game —without a word of explanation.”

Walton was undercut by a Washington State player at the peak of his jump [there is one split second when even the nimblest athlete can’t adjust their fall]. The “despicable act of violence” resulted in two broken bones in his spine.

Walton spent 11 days in the UCLA hospital. On January 19, 1974 he “strapped on a corset with vertical steel rods in it for support” and flew to Chicago for the game against Notre Dame.

“At halftime we had a 17 point lead, but Greg didn’t play at all in the second half. We had an 11 point lead and the ball with three minutes to go, in an era that predated the shot clock and the three-point shot. And we gave it all way, losing by one as we went scoreless for the rest of the game… and turning the ball over four times…

“I’ve concluded there was nothing as devastating as the continued presence in the lineup of Tommy Curtis. Tommy’s increased role and playing time came at the expense of Greg, who was the real key to our team’s offensive flow…

“Greg, as a solid position defender, could read and anticipate the defensive play that would start our fast break. Whether it came from a block, steal, deflection or rebound and outlet, he was on the move, up the court, continuing to build on a play that had already been made. Tommy, no matter what, always came back to the ball, disrupting the flow and advantage that had already been created.

“Greg was always ready to make the next pass ahead, quickly moving things forward. Tommy seemed interested only in making the play himself, invarainvariably off his own excessive and irritating dribble. And we were never a team that

“Greg was the master at delivering the ball to a teammate on the move, coming off a screen on a backdoor cut or lob, or just flashing to an opening.

“Tommy was so insistent on dribbling for his own play and shot that we would be on the move, finding key openings and calling for the ball, only to have to stop, wait, and ultimately lose our advantage as he pounded ball, back and forth, through his legs, in and out —anywhere and everywnere except where it needed to go.

“And Tommy was always talking to the other team, their coaches, the refs, the fans. It was always, ‘In you fact,’ ‘In you eye,’ ‘Your mama,’ ‘Too late,’ ‘Get back,’ ‘Stay down.

“It was all so depressing. And every day I would be in coach Wooden’s office pleading, explaining, begging for sanity, rationality, reason. But all to no avail. As Greg sat for extended periods and Tommy continued to get more and more of everything, Coach would just sit there with a blank stare as I tried to get him to see what was so painfully obvious to me.”

In February UCLA lost on the road to Oregon and Oregon State. “Greg hardly played at all in either game,” according to Walton. “Turnovers, uncertainty, hesitancy and doubt plagued every aspect of our existence.”

Greg Lee was reinserted as a starter towards the end of the season and UCLA stopped losing, “But we still lacked the perfect consistency and flawless execution that had been our standard for years.” In the NCAA tournament, the team squeaked by Dayton (Lee was benched after Dave Meyers let a pass go through his hands). Then they beat USF and met North Carolina State (with the great David Thompson) in the semi-finals. Walton’s refrain: “Turnovers, missed free throws, offensive fouls, and Tommy Curtis all cost us down the stretch.” NC State won in double overtime. For the Bruins, reefer madness had culminated in March sadness.

“Back From the Dead” reminds us how strong the anti-marijuana prejudice can be —strong and ineradicable in otherwise righteous people. And nobody’s perfect. Nobody bats a thousand, not even those we admire most.

Bonus track: Patty Hearst & Bill Walton Revisited