In 1934 President Franklin D. Roosevelt created a Committee on Economic Security to draft legislation that would lift millions of Americans out of poverty. The five-member group drafted a bill that would cover all workers. It would provide some income in old age, a stipend in the event of disability, and health insurance. The CES draft was altered at the last minute by Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr. presumably with the president’s backing or at his request.

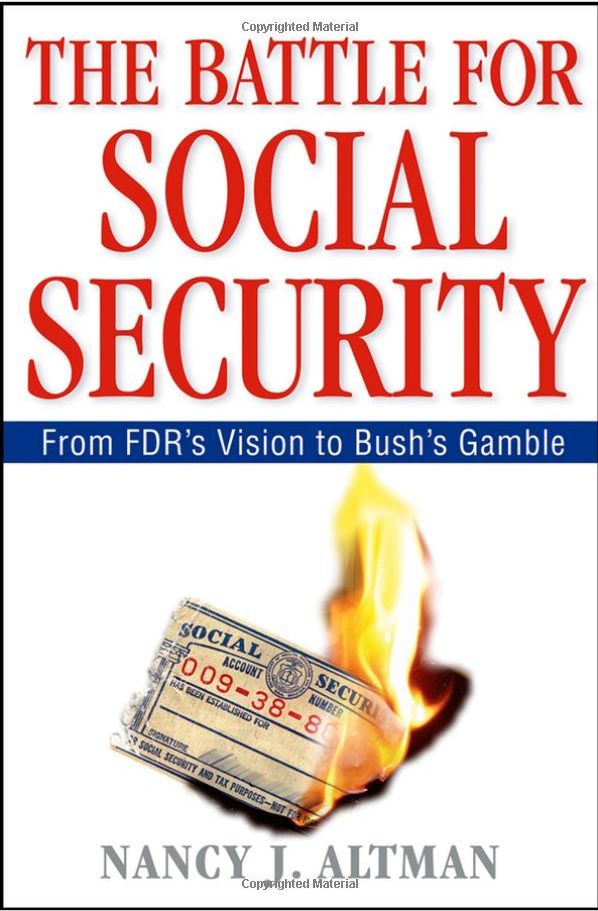

Morgenthau’s appearance before the House Ways and Means Committee in support of the bill is vividly described by Nancy Alman in The Battle For Social Security:

In its deliberations the prior December, CES had agreed, as a fundamental principle, that old-age insurance should be universal, in order to provide everyone with the important protection and to establish a broad insurance pool over which to spread the risk. The cabinet-level group had recommended to the president that all workers be covered with the only exceptions being federal workers covered by the relatively new civil service retirement system, railroad workers covered by the recently enacted Railroad Retirement Act, and state and local workers, with respect to whom there were constitutional questions involving state sovereignty.

Morgenthau had a representative at all CES deliberations and had signed its report to the president. Morgenthau had not been reticent, even at the eleventh hour, about objecting to the proposed financing scheme contained in the report. But he had never breathed a word of objection to the decision to propose nearly universal coverage.

Nevertheless, at the hearing, Morgenthau asserted that the Treasury Department believed it would be extremely difficult to collect payments from agricultural workers, domestic workers, and employers with only a few employees. With Secretary [of Labor Frances] Perkins seated next to him at the witness table, her eyes widening and her jaw dropping, he urged Congress to restrict coverage of the legislation to these involved in ‘commerce and industry,’ about 60 percent of the workforce. As the members of the committee nodded their heads in agreement Perkins sat frozen in shock and disbelief.

A motion to strike the old-age insurance piece had been leading by one vote within the Ways and Means Committee, according to Altman, when Morgenthau made his unilateral concession. Then:

Representative Frederick M. Vinson… worked out a deal in which the lead supporters of the president’s proposal would vote to strike the voluntary annuities, if, in exchange, the hesitating members would support compulsory old-age insurance.

And that’s how most of the Black folks in the South and many struggling white folks throughout the land were excluded when Social Security was enacted in 1935. Altman says that before the bill was reported out, “someone on the Ways and Means Committee moved that the name of the bill be changed from the Economic Security Act of 1935 to the more alliterative Social Security Act of 1935.” More alliterative but less meaningful.

Two years later, as he was ramming through the Marijuana Tax Act, Fred Vinson could come on as a populist, lambasting the AMA for opposing Social Security. The hypocrite had effectively opposed Social Security for 40% of the work force.

Morgenthau to Wallace, March 25, 1938 “Marihuana Tax Act of 1937,” National Archives. He had been contacted by Harry Strauss. Lupien” Morgenthau “mentioned some experimentation which the Treasury and Agricultural Departments had jointly conducted over the summer of 1937. These experiments revealed “that there was a tendency on the part of the Some of Cannabis plants to be lower than others in narcotic content.” On the basis of this discovery, Secretary Morgenthau suggested that it might be possible to breed a strain of cannabis that was totally free of the drug. Such a project would be beneficial to agriculture and industry. In order to facilitate this avenue of research, M. proposed that Treasury and Ag should “consider utilizing the approacirations available under the Ag Adjustment Act of 1938, which provided $4 million to develop crops. He concluded by stating that hemp would cease to exist as an agricultural commodity unless action was taken to insure its legimitamte industrial usage. Wallaces response was “not posibitive.” WHY WAS GREGG “Acting Secretary?” in 38. Gregg suggested research would have to wait until the chemists identified the psychoactive component.

Gregg makes reference to uAg Dept experiments in Ames “into the utilizatio of hemp hurds toward th production of cellulose.”