Recent CDC laboratory testing of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples (or samples of fluid collected from the lungs) from 29 patients with EVALI submitted to CDC from 10 states found vitamin E acetate in all of the BAL fluid samples. Vitamin E acetate is used as an additive in the production of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. This is the first time that we have detected a potential chemical of concern in biologic samples from patients with these lung injuries.

CDC continues to recommend that people should not use e-cigarette, or vaping, products that contain THC, particularly from informal sources like friends, or family, or in-person or online dealers. We will continue to provide updates as more data become available.

On November 4 Leafly posted a lucid, well-researched piece by Marissa Wenzke and David Downs about the culprits. chemical and human. They explain:

Industrial chemical manufacturers have sold vitamin E oil for years, but only as an ingredient in hand lotions or gummy vitamins. So who turned tocopheryl-acetate into a wildly popular and potentially deadly vape cartridge additive?

Multiple industry experts point to a mysterious, low-profile Los Angeles company called Honey Cut. By creating a new category of “thickening” vape cartridge additives, Honey Cut became a nationwide phenomenon. Its formula—and copycat products just like it—suddenly turned up last year in illicit THC vape cartridges nationwide.

Don’t expect the sad epidemic to come to an abrupt end, partly because of those “copycat products.” As the Leafly team note,

“Vape cartridge makers are continuously developing more novel additives, just as the makers of performance-enhancing drugs keep innovating to stay one step ahead of anti-doping agencies… With a few clicks, anyone can find images of the company’s logo online, print it out on stickers, and start selling re-labeled jars of vitamin E oil on Ebay. Chinese authorities have promised to start clamping down on supplies, but the product remains just a Google search away.”

Although many media outlets are now describing Vitamin E oil as the cause of vape-related lung damage, analytic labs have found significant pesticide and herbicide residues in cannabis oil (and flowers). Unscrupulous producers also use synthetic cannabinoids like “Spice” instead of plant extracts in the oil they fill their vape cartridges with.

Although most of the EVALI patients reported having vaped THC, 11% “reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products,” according to a CDC survey posted October 15. So e-cigarettes are not in the clear.

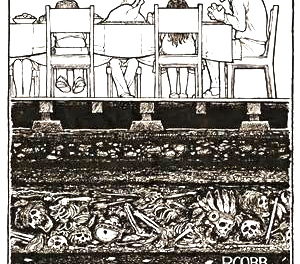

Although the coils and batteries of vape pens were not implicated in the EVALI epidemic, if cheaper versions with a less benign safety profile become available, unscrupulous ganjapreneurs will market them.

Wenzke and Downs provide this relevant background:

Most vaping devices pair a rechargeable battery with a screw-on reservoir (known as a cartridge) filled with either liquid nicotine or THC oil. Vapes dispensed low doses of THC without the telltale odor of burning cannabis, and the small size of the devices offered discretion amid the social stigma—and criminal penalties—attached to the use of cannabis.

In 2012, THC vape products barely registered as a market category. Six years later, they accounted for half of all THC extract sales and a quarter of all product sales, according to BDS Analytics.

In 2013, researchers at Northwestern University published a study that may have indirectly inspired a host of unintended consequences. “Two Faces of Vitamin E in the Lung,” printed in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care, described alpha tocopherol—one of eight closely-related chemicals in the vitamin E family—as potentially helpful for some pulmonary conditions. The study found that the substance, available in sunflower oil and olive oil, could protect humans from adult-onset asthma and might have a “beneficial effect on lung function.”

One of the study’s critical details, though, was that the researchers were studying the effects of eating vitamin E, not inhaling it.

Two years later, in 2015, Constance Finley applied for a patent on a vape pen containing CBD and vitamin E. Finley is the founder of the San Francisco medical cannabis company Constance Therapeutics,

Finley ran her idea by an organic chemist, a molecular biologist, and a clinical herbalist before analyzing what happened when they heated alpha tocopherol to 750°F. Large-scale clinical research simply didn’t exist.

“We did what we could,” Finley told Leafly. “We analyzed what came out of the vapor in a balloon study.”

According to Finley, more than 4,000 customers over seven years used her company’s product without incident. She contends that one form of the chemical—alpha tocopherol—is safe in low amounts, while other forms, like tocopheryl-acetate, may not be. No peer-reviewed studies exist to confirm or disprove this thesis.

Finley’s patent application for the use of vitamin E in vape pens may have inspired Honey Cut. Patent applications are public documents, available to anyone online.

“What we’re told is all these people that started using vitamin E acetate did so by copying our patent,” Finley said. But the copy either proved to be imperfect, or the knockoff artists deliberately altered the formula to avoid infringing on Finley’s pending patent. “I was shocked and kind of horrified to have this influence,” she said. “Because it’s really stupidity.”