January 30, 2020 “California officials announced Monday that marijuana vape cartridges seized in illegal shops in Los Angeles contained potentially dangerous additives, including a thickening agent blamed for a national outbreak of deadly lung illnesses tied to vaping.”

So begins an Associated Press story that quotes Lori Ajax, head of the Bureau of Cannabis Control, promoting the legal industry: “The prevalence of dirty and dangerous vape pens at unlicensed cannabis stores demonstrate how important it is for consumers to purchase cannabis goods from licensed retailers, which are required to sell products that meet state testing and labeling standards.”

Facts in the story support Ajax’s point:

“The state conducted tests on the marijuana oil contained in a random sample of more than 10,000 illegal vape pens seized in the Los Angeles raids. The tests found that 75% of the vapes contained undisclosed additives, including the thickening agent vitamin E acetate, which has been blamed by federal regulators for the majority of lung illnesses tied to the outbreak.

“In some samples, oil in the cartridges was diluted by more than one-third by potentially dangerous and undisclosed additives.

“Nearly all the samples were labeled with incorrect THC content… Some vape products seized from the unlicensed stores contained as little as 18% THC.

“Last Thursday, regulators proposed rules that would require legal shops to post a unique black-and-white code in storefront windows to help consumers identify licensed businesses. Shoppers would use smartphones to scan the familiar, boxy label known as a QR code — similar to a bar code — to determine if businesses are selling legal, tested cannabis products. The codes also would also be required when transporting or delivering cannabis.

“The state has been escalating its war with the illegal market under pressure from the legal cannabis industry, which has struggled as consumers go underground looking for bargain prices. But there is a trade-off: illegal products almost certainly are not tested for safety or potency.”

It would be interesting to know what percentage of the >10,000 samples were thickened with Vitamin E acetate, the main culprit identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Also, how many samples tested positive for the anti-fungal myclobutanil (Eagle 20), and the insecticides bifenazate (Floramite) and abamectin (Avid). All are widely used, often by growers who intended to rely on organic pest-control methods but couldn’t resist the synthetic poisons when powdery mildew or earwigs threatened their income.

The AP story quoted above was sent to us by Steve Robinson, MD, president of the Society of Cannabis Clnicians and Dale Gieringer, director of California NORML. Obviously, vape-related lung damage and the legal status of vaping are matters of great concern to doctors and reformers.

Cassandra Predicts

Vape-related lung damage has frightened consumers, led to outright bans in many jurisdictions, and made a dent in the legal vendors’ sales. But in due course it will turn out to be a boon for them, just like poisoned Tylenol turned out to be a boon for Johnson & Johnson. As it becomes widely known that all the lung-damaging vape products have come from unregulated manufacturers via unregulated vendors, consumers will have a strong incentive to buy from the more expensive legal vendors. And law enforcement can and will righteously shut down the unregulated outlets, which currently account, it is said, for 3/4 of cannabis sales in California. Once reviled as paramilitary narcs, agents conducting raids will be honored as public-health enforcers. It’s already happening.

The powerful public-relations man who orchestrated Johnson & Johnon’s response to the poisoned Tylenol episode, Harold Burson, died earlier this month at the age of 96. In addition to J&J, Eli Lilly and other pharmaceutical makers, his clients included Philip Morris, Merrill Lynch, Coca-Cola, Shell, ExxonMobil, General Motors, Dow Chemical, IBM, American Express and Citicorp. This is how the New York Times described The Great Burson’s advice to J&J

“When cyanide-laced capsules of Tylenol, the pain medication, killed seven people in the Chicago area in 1982, its manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, made the best of a bad situation. After consulting Mr. Burson, the company’s chief, James E. Burke, announced a recall, ordered new tamper-resistant caplets and packaging seals, and mounted a campaign that acknowledged the facts, stressed safety measures and eventually restored his company’s credibility… The Tylenol case is often cited as a textbook model of corporate responsibility in a crisis.”

Johnson & Johnson’s strategy was actually one of the most irresponsible and destructive marketing schemes ever deployed by a manufacturer. Yes, the prompt recall and reimbursement of customers was shrewd and widely appreciated. Yes, giving out discount coupons at drug stores induced people to buy Tylenol when it was reintroduced. But the key step in rebuilding and vastly expanding sales of J&J’s supposedly-safer-than-aspirin analgesic was to engulf each bottle in triple-seal, tamper-resistant packaging. Tylenol may have been the first over-the-counter drug to get this level of gratuitous “protection.” It was certainly the first product for which the plastic packaging itself became the essential selling point.

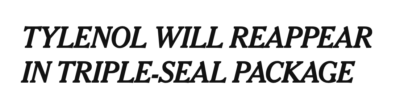

On November 11, 1982, less than a week after J&J recalled Tylenol, the company announced plans for its reintroduction. The Times headline conveyed the key fact:

It was a brilliant marketing ploy. The hard plastic outer layer proclaimed “safety” and a faint overtone said “purity.” As Tylenol sales rebounded and kept rising, other manufacturers started sealing their products in plastic —not just drugs for internal consumption, but a wide variety of commodities were given unnecessary see-through packaging. Who hasn’t struggled to cut through the hard plastic in which, say, a new stapler or flashlight was mummified? The oceans are now polluted with countless tons of plastic produced to seal things that did not and do not need sealing.