“The United States is in the throes of a colossal health crisis,” writes Helen Epstein in the New York Review of Books, March 26 2020 — assessing two books: “Deaths of Despair and the Future of American Capitalism” by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, Princeton University Press, and “Pain and Politics in the Heart of America” by Jennifer M. Silva, Oxford University Press. Epstein’s fact-filled essay was written before the Covid-19 catastrophe began unfolding in the US —which makes it even more poignant.

In 2015 life expectancy began falling for the first time since the height of the AIDS crisis in 1993. The causes—mainly suicides, alcohol-related deaths, and drug overdoses—claim roughly 190,000 lives each year.

The casualties are concentrated in the rusted-out factory towns and depressed rural areas left behind by globalization, automation, and downsizing, but as the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton demonstrate in their new book, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, they are also rampant in large cities. Those most vulnerable are distinguished not by where they live but by their race and level of education. Virtually the entire increase in mortality has been among white adults without bachelor’s degrees—some 70 percent of all whites. Blacks, Hispanics, college-educated whites, and Europeans also succumb to suicide, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths, but at much lower rates that have risen little, if at all, over time.1

The disparity is most stark in middle age. Since the early 1990s, the death rate for forty-five-to-fifty-four-year-old white Americans with a BA has fallen by 40 percent, but has risen by 25 percent for those without a BA. Although middle-aged blacks are still more likely to die than middle-aged whites, their mortality has also fallen by more than 30 percent since the early 1990s. Similar declines occurred among middle-aged French, Swedish, and British people over the same period.

Case and Deaton show how this crisis worsened over generations, beginning with the Baby Boomers. College-educated whites born before World War II were slightly more vulnerable to suicide, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths than non-college-educated whites, but these trends reversed among those born after the war, and then the fates of those with and without a BA continued to diverge.

Growing economic insecurity is a major cause of the problem. White manual workers once expected that the American Dream would come true for them. In Kathryn Newman’s remarkably prescient study of downsizing, Falling from Grace (1988), older people recalled that Elizabeth, New Jersey—where 18 percent of residents now live in poverty—was once a “place of grandeur, where ladies and gentlemen in fine dress promenaded down the main avenue on Sunday.” The Singer Sewing Machine company employed over 10,000 workers, roughly a tenth of the city’s population. The company awarded scholarships to children, sponsored baseball games, and hosted dances and bar mitzvahs in its recreation hall. Each sewing machine had a label, and if returned with a defect, the man who’d made it would fix it himself.

The last American Singer plant closed decades ago, along with thousands of other factories. There were 19.5 million decently paying US manufacturing jobs in 1979, compared to around 12 million today, when the population is almost 50 percent larger. Over the same period, the wages of workers with a high school degree or less have fallen by about 15 percent, while the earnings of college-educated workers have risen by around 10 percent and of those with higher degrees by nearly 25 percent.

Today, what’s available to those without a BA are mostly poorly paid service jobs without health or retirement benefits, let alone baseball games and scholarships. The demise of unions means that these workers have virtually no bargaining power. One in five US workers is subject to a noncompete clause, meaning they can’t easily move from one company to another without switching fields completely. Until recently, even chain restaurant workers could be subject to such rules, so that a burger flipper at Carl’s Jr. who was offered higher pay at Arby’s couldn’t accept it without risking a lawsuit.

Andrew Cherlin and Timothy Nelson recently interviewed dozens of American men without BAs, most of whom bounced from one dead-end job to another. One unemployed man had started out as an editorial assistant at a local newspaper but was laid off when it downsized; he became a parking attendant, but that job was eliminated by automation; he then worked for a catering company until it went out of business.2

The personal lives of those without a BA mirror this instability. The vast majority of women with a BA have all their children in marriage, but most women without one have at least some, if not all, of their children out of wedlock, often with different men. American children experience more changes in stepfathers, stepmothers, and residences than children in any other wealthy country, and Cherlin maintains that American families may be the most unstable in the world. This no doubt contributes to many child development problems that are also common in the US, including difficulties sitting still and paying attention in school, disobedience, and destructive behavior. Children with these issues often find it difficult to enter, let alone finish, college, perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of thwarted potential.

Some conservatives, such as Charles Murray and J.D. Vance, the author of the wildly popular memoir Hillbilly Elegy, attribute these economic and social upheavals to moral decline. If only poor whites would embrace religion, adopt the family values of their better-educated peers, stop blaming the government, and work harder, they’d be fine, they say. But as Case and Deaton point out, if it were really true that workers without BAs were slacking off, wages would have risen for those who weren’t, but this hasn’t happened. The jobs just aren’t there—or if they are, they don’t pay enough to support a dignified existence. About half of those who patronize America’s food banks live in households with a full-time worker—perhaps a janitor, Uber driver, cashier, nanny, or caregiver—who doesn’t earn enough for groceries. According to the Urban Institute, about a quarter of adults in homeless shelters have jobs.

But while poverty in America is all too real, it’s not the only reason for the epidemic of deaths of despair. Poor states like Arkansas and Mississippi have seen smaller increases in overdose deaths than wealthier Florida, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Maine. Deaths of despair continued their steady rise right through the 2008 financial crisis, when many Americans lost homes and jobs, and didn’t jump in frequency, as we’d expect if economic circumstances alone were the cause. Blacks without a BA earn between 20 and 27 percent less than whites without a BA, but even though addiction remains a problem in African-American communities, non-BA blacks are nevertheless 40 percent less likely than non-BA whites to die from suicide, alcohol, or drug overdoses.

If poverty alone can’t explain this epidemic, what’s going on? Case and Deaton suggest that it may have something to do with the ways in which non-BA whites have responded to the radical changes that have upended their world over the past century or so. The post-1970s economy inflicted suffering on non-BA people of all ethnicities, but the psychological toll on whites might have been worse because their expectations were so much higher. Financial hardship has long been part of historical reality for black Americans, often attributed, rightly, to discrimination. Perhaps for this reason, blacks are more likely to sympathize with poor and unemployed friends and relatives, and help out when possible. Europeans are similarly likely to see their personal misfortunes in political terms, blaming their governments and even taking to the streets to protest fiscal policies they see as harmful, as the French are doing now.

But white American men tend to be especially hard on themselves. They often find in their occupations the self-worth and community that other groups find in kinship and class consciousness, so their sense of personal worthlessness can be profound when jobs are unstable or disappear.

For Falling from Grace, Newman interviewed men laid off after a downturn in the computer industry during the 1980s recession. Even though the entire industry was affected, most men dwelled only on what was wrong with them. The problem, they explained to Newman, wasn’t a ruthless corporate culture or the laissez-faire government that had just hiked interest rates, causing the collapse of fragile businesses, but themselves. “If people…are not prospering, that’s their problem,” John Kowalski, sacked from his company after thirty years of service, told Newman. Meanwhile, friends stopped calling; wives accustomed to a comfortable lifestyle glowered and complained; children shrank away in confusion.

The decline in blue-collar jobs has been far more sustained than the periodic glitches in the white-collar economy, but whites without a BA haven’t thus far used their considerable political clout to improve their situation. As has repeatedly been pointed out, many don’t vote, while others support corporate-backed Republicans hostile to the very programs many poor whites depend on, including food stamps, job training, social security, Medicaid, and unemployment and disability benefits.

During the run-up to the 2016 election, the sociologist Jennifer Silva interviewed people in the Pennsylvania coal region, which delivered Trump a two-thirds majority, to find out how they made political decisions. Pennsylvania’s coal mines, which once employed 175,000 people, now employ just 837. With those jobs went an entire way of life. The work was dangerous and dirty; thousands died in accidents or succumbed to black lung disease; miners depended on company stores and homes, and those who lost their jobs faced destitution; but they nevertheless had a profound sense of solidarity. Most marriages lasted a lifetime, and communities were held together by social clubs, churches, unions, and friendships.

Today, Coal Brook, the (pseudonymous) town that Silva describes in We’re Still Here, is a depressed wasteland of bars, chain stores, fast food restaurants, and drug rehab centers. Most of the white, black, and Hispanic men and women Silva interviewed struggled with drug or alcohol problems, had spent time in jail, and/or were unemployed. Virtually all said that voting was pointless because the system was rigged in favor of the rich. When Silva turned up for an interview on Election Day wearing an “I Voted” sticker, she was mocked as a gullible fool.

“All politicians are bought off,” declared Joshua, a twenty-eight-year-old white ex-con in drug recovery. “Once they get thrown into the machine they become puppets like all the rest…. I’m not a fan of either [Trump or Clinton]. It’s like choose shit or a shit sandwich.”

Bree, a white waitress suffering from chronic pain whose black boyfriend was recently released from prison, felt similarly:

I love women, and I think they can do anything a man can do, but that woman should not be the President of this United States, so help me God, but neither should that jackass. So it’s like, who the frick do you pick? I’m like, you’re not giving us much of a choice here. Either way we’re going to be destroyed.

Very few of the people of color interviewed by Silva bothered to vote at all, but some whites held their noses and voted for Trump. “Oh, he got us rednecks!” said Steven, a sixty-two-year-old janitor. Danielle, a twenty-eight-year-old child abuse survivor with debilitating anxiety, put it this way: Trump is “so in your face, like eff you, I don’t give a crap what you think of me. I think he belongs in this area because that’s what we are.” Bree agreed: “At the end of the day, I would rather have President Dickhead than President Sellout.”

The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu was the first to observe that what made the new “precariat” class—as he called the intermittently employed, low-wage workforce—so vulnerable was that its solidarity had been ruined.3 When workers are made to feel replaceable and lucky to have even a lousy job, they become cynical, competitive, depressed, and easier to exploit. A growing number of researchers are finding that instead of turning to politics, many poor Americans are turning inward, focusing on their own personal struggles with trauma and pain.4 One of Case and Deaton’s most striking findings is what I’ll call the “pain paradox.” On national health surveys, sixty-year-old white Americans without a BA are two-and-a-half times more likely to report that their health is fair or poor than same-aged whites with a BA. Even though working-class jobs involve less risk and physical exertion than in the past, each generation of non-BA whites since the Baby Boom has reported more pain, at younger ages, than the previous one. Non-BA blacks, who tend to do the most physically grueling jobs, are 20 percent less likely than non-BA whites to report pain at all ages. Even odder, non-BA whites actually report more pain at age sixty than at age eighty, whereas the reverse is true for blacks, whites with a BA, and populations in nineteen comparison countries.

The pain experienced by non-BA whites is so severe it’s keeping many of them from working altogether. In 1993 4 percent of forty-five-to-fifty-four-year-olds without a BA were out of the workforce for health reasons; today, 13 percent are. In Virginia’s coal region, the journalist Beth Macy found that in one county, 60 percent of men were either unemployed or living on disability payments.5

This pain seems to be real. At no time do Silva or Macy suggest that anyone is faking it in order to live large on food stamps. But a combination of prescription and recreational drug use, sky-high smoking rates, depression, anxiety, and other emotional problems—which may worsen the actual feeling of pain, according to neuroscientists6—along with poor access to good health care, seems to have amplified the effects of work injuries, accidents, and the physical and emotional scars of domestic violence and trauma resulting from military service.

Pain, observes Silva, has become a powerful organizing factor in the lives of just about all of Coal Brook’s adults. But ethnic differences in the way people respond to their afflictions could help explain white hypervulnerability to deaths of despair. The lives of Silva’s black and Hispanic informants, like those of the whites, were full of school failure, incarceration, addiction, and health problems. On top of that, they faced raised middle fingers and muttered N-words in the streets. They felt unwelcome at churches and sporting events, their kids were bullied by white classmates, and they were keenly aware of racism in the criminal justice system and in their workplaces. But their vision of the future tended to be less hopeless and bleak than that of the whites. One, for example, obsessively read self-help books, and another proudly showed Silva his prison diplomas from parenting and accounting classes. Perhaps because most of them grew up in urban ghettos, Silva’s poor blacks and Hispanics expected things to turn out even worse, and for them, Coal Brook was almost a land of opportunity, if a shabby and disappointing one.

Silva’s white informants, by contrast, tended to see themselves as lonely warriors facing strange, undefined threats to their community. Weird conspiracy theories were common. Graham Hendry, a white nursing-home aide who’d been chain-smoking since age nine and had recently lost three friends to heroin, believed that September 11 and the Sandy Hook school massacre were hoaxes, that FEMA was building a network of concentration camps for minorities, and that the government put fluoride in toothpaste and aluminum chloride in deodorant in order to calcify people’s pineal glands, allowing the authorities to control their minds.

“Everybody is getting cancer,” Mary Ann Wilson, a fifty-one-year-old white smoker, told Silva. “There’s something in the air,” said her adult daughter Vivian, also a smoker. Could it be landfill from those trucks from New York, they wondered? Or the dust kicked up by the mines?

Many of the white men carried guns everywhere—to high school football games, the supermarket, the sub shop. Their anger focused on a faceless government that neglected people like them and on supposedly shiftless immigrants and minorities who feasted at the public trough. Some embraced white nationalist ideas, which unconvincingly concealed deep feelings of loneliness, shame, worry about the future, and a yearning for solidarity.

Other white men adhered to a stoic and lonely individualism. Jacob, divorced from his unfaithful wife, discharged from the navy for health reasons, and having failed a test to become a construction foreman, still believed in self-reliance and self-sacrifice and had the word “courage” tattooed all over his body. Joshua, the nonvoting twenty-eight-year-old, sought a Zen-like suspension from the world: “I think if we live with a fearless approach to life with unconditional love, then we can be the stillness in the chaos, we can endure.”

Whereas most whites aspired to a lonely-hero ideal, many of Silva’s nonwhites upheld an image of what the sociologist Michèle Lamont has called the “caring self”—altruistic, part of a mutually supportive kin network, cognizant of how their own suffering linked them to that of past generations. And they found real hope in their children, whom they attempted to shield from racism. The whites were also devoted to their children but were often so preoccupied with their own problems that they struggled to be good parents.

Addiction, violence, and despair are common to all human societies that have seen their cultures destroyed, whether South Africans uprooted by apartheid, Native Americans herded onto reservations, or African-Americans stranded in urban ghettos. The psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove calls it “root shock,” the loss of one’s emotional ecosystem following the destruction of cultural, social, and political capital resulting from mass displacement, natural disaster, or economic upheaval. The anthropologist Oscar Lewis observed it in rural migrants trying to eke out a living in the slums of Mexico City; Ralph Ellison witnessed it during the Great Migration among black migrants who discovered that mid-twentieth-century Harlem wasn’t necessarily the promised land after all. In his 1964 essay “Harlem Is Nowhere,” Ellison wrote that in the South, a stable family structure, authoritative religion, and “techniques of survival which…[made] Hemingway’s definition of courage, ‘grace under pressure,’ appear mere swagger,” enabled them to endure Jim Crow racism. But in the North, without those supports, they lacked one of the bulwarks which men place between themselves and the constant threat of chaos. For whatever the assigned function of social institutions, their psychological function is to protect the citizen against the irrational, incalculable forces that hover about the edges of human life like cosmic destruction lurking within an atomic stockpile.

Out of the ashes of the current catastrophe, America’s white working class seems to have fashioned a new culture of pain and trauma, rooted in white America’s peculiar imperative to seem happy all the time (unless you’re sick) and to personalize and depoliticize financial hardship. This self-defeating belief system is reinforced by neoliberal “government is the problem” slogans and self-help gurus such as Melody Beattie, author of Codependent No More, who warn against getting wrapped up in other people’s problems. “If Tori dies, that’s on her,” one of Silva’s informants said of her drug-addicted sister.

This new culture flourishes amid rampant pharmaceutical marketing that shunts vulnerable depressed people onto a path, via side effects and addiction, to further health problems. Entry into this culture starts early. In Virginia coal country, Beth Macy was told that some parents, worried about their children’s financial prospects, urged their pediatricians to diagnose them with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, so that they might eventually qualify for disability. Ritalin, most often prescribed for ADHD, is a “pipeline” drug to the disability rolls, a local health official told her. A doctor who worked at a summer camp said that in the 1970s, very few kids were on prescription medications, but now one third are, mostly for ADHD and depression, but sometimes even for psychosis.

The victims of America’s pain epidemic might be experiencing something similar to what Frantz Fanon called North African Syndrome—a mixture of stomach ailments, vague aches and pains, heart palpitations, and headaches that afflicted Algerian migrants in France during the 1940s. Baffled French doctors could find no physical cause, and treatment offered no relief, so they dismissed their patients as malingerers. But Fanon, channeling Jean-Paul Sartre’s equation of existential despair with physical nausea, understood that these migrants, raised to believe that they were part of a great French empire, were responding to the mental agony of loneliness. Poor and adrift on the outskirts of French cities, rejected and condescended to by French people, they were liminal and lost, even to themselves.

Opioids, my drug-using friends say, don’t just ease pain. They liken the effect to the warmth of bonding with a newborn or being praised for a great piece of work. These drugs stimulate the dopamine system in the brain, which, among other things, helps make the world appear more meaningful. No wonder they seem to be the perfect medicine for the anomie that is blighting so many American lives.

There are solutions to this disaster. Case and Deaton would like to see tougher rules for prescribing opioids, the regulation of outsourcing firms so they don’t exploit workers, a stronger safety net for the unemployed, increased access to higher education, and more and better retraining programs for people in depressed areas. Corporate mergers should be better scrutinized to ensure they aren’t devouring competition, and wages and tax credits for the poor should be increased.

But most of Case and Deaton’s ire focuses on the health care industry, which not only underperforms but is also wrecking the US economy. We spend twice per capita what France spends on health care, but our life expectancy is four years shorter, our rates of maternal and infant death are almost twice as high, and, unlike the French, we leave 30 million people uninsured. The amount Americans spend unnecessarily on health care weighs more heavily on our economy, Case and Deaton write, than the Versailles Treaty reparations did on Germany’s in the 1920s.

If, decades ago, we’d built a health system like Switzerland’s, which costs 30 percent less per capita than ours does, we’d now have an extra trillion dollars a year to spend, for example, on replacing the pipes in the nearly four thousand US counties where lead levels in drinking water exceed those of Flint, Michigan, and on rebuilding America’s bridges, railroads, and highways—now so run-down that FedEx replaces delivery van tires twice as often as it did twenty years ago. Median income growth over the past thirty years would have been twice what it actually was, and many of the 45,000 uninsured Americans who die annually because they can’t afford care might be alive. More and better jobs might also be available to people without BAs. In the US, health insurance accounts for 60 percent of the cost of hiring a low-wage worker. Many employers opt instead to hire contract workers with no benefits, or illegal immigrants with no rights at all.

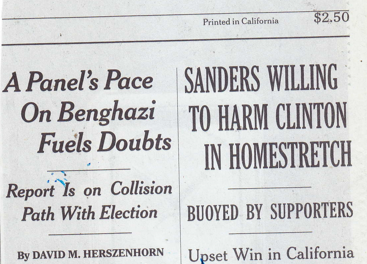

Silva’s Pennsylvania informants, including those most critical of minorities on welfare, do support the expansion of access to education, health care, fair pay, and good jobs. “A political candidate who puts economic justice for working-class families at the center of their platform,” she notes, “and who does not shy away from criticizing the collusion of financial and political elites, could have a shot at gaining their support.” Interestingly, many informants, including Trump supporters like Steven, the sixty-two-year-old janitor, indicated that they would have voted for Bernie Sanders had he been on the ballot in 2016. It’s worth noting that 117,000 Pennsylvanians who voted for Sanders in the primary cast their general election ballots for Trump, who won the state by only 44,292 votes.

If you include those who have left the workforce altogether, the US unemployment rate is almost as high as it was in 1931. Back then, the grandfathers of today’s non-BA whites were drawn to Franklin Roosevelt, who supported generously funded public works programs and expressed open contempt for greedy corporate tycoons. Perhaps a Democratic candidate with similar policy positions will offer America’s struggling workers a reason to go to the polls in 2020 without feeling like fools.

1 Although this may be changing, as deaths of despair seem to be increasing among people of color in the US and in the UK. ↩

2 Andrew J. Cherlin, Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America (Russell Sage Foundation, 2014), p. 154. ↩

3 Pierre Bourdieu, “La précarité est aujourd’hui partout,” Grenoble Conference, December 12–13, 1997. ↩

4 “Pathologizing Poverty: New Forms of Diagnosis, Disability, and Structural Stigma under Welfare Reform,” by Helena Hansen, Philippe Bourgois, and Ernest Drucker, Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 103 (February 2014). ↩

5 Beth Macy, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America (Little, Brown, 2018), p. 125. ↩

6 “Induction of Depressed Mood Disrupts Emotion Regulation Neurocircuitry and Enhances Pain Unpleasantness,” by C. Berna et al., Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 67, No. 11 (June 1, 2010).