Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s connection to the Hallinan saga is indirect and faint, but the AVA is a newspaper, above all, and the Supreme Court is now Action Central as Antonin Scalia’s protege ascends; so here’s the relevant background.

California voters legalized marijuana for medical use in November, 1996. In December ’96 secret meetings were held in Washington, DC, at which Clinton Administration officials assured California law enforcers and private-sector Drug Warriors that they would take action to curtail implementation of the new law. In January ’98 the US Department of Justice invoked the rarely used civil provisions of the Controlled Substances Act against six Bay Area dispensaries, including Dennis Peron and the recently renamed San Francisco Cannabis Cultivators Club; Jeff Jones and the Oakland Cannabis Buyer’s Cooperative (OCBC); Lynette Shaw and the Marin Alliance for Medical Marijuana (represented by the late Carl Shapiro, a friend of the AVA); and Marvin and Mildred Lehrman and the Ukiah Cannabis Buyer’s Club. This was the Clinton Administration’s triangulated and politically tragic response to the passage of Prop 215.

Bill Clinton could have and should have said, “We are very concerned and the Centers for Disease Control and the Public Health Service will be monitoring California very carefully…” And then, when no ominous patterns ensued from widespread marijuana use, the Democrats could have taken credit for allowing the popular reform to take root. It probably would have meant a victory for Al Gore in November 2000 (by which time eight states had passed medical MJ laws).

“The feds used the civil injunction instead of filing criminal charges because they want to avoid a jury trial on the clubs’ right to operate,” was District Attorney Hallinan’s analysis back in ’98. Dennis Peron asked him to file fraud charges against five DEA agents, identified in court documents, who had falsified doctors’ letters of diagnosis to gain membership in his club. Terence said it wasn’t do-able.

US District Court Judge Charles Breyer ruled that the cannabis clubs were not entitled to a defense on grounds of “medical necessity.” Attorney Robert Raich, representing Jones and the OCBC, got a ruling from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal instructing Breyer to modify his injunction to acknowledge that individual patients might have a medical necessity to use marijuana. Breyer did so, and on July 17, 2000, Hallinan issued a press release magnifying its significance:

“Judge Breyer’s ruling is courageous and historically significant. It’s a victory for everyone who voted for Prop 215. A major conflict has been removed for law enforcement: medical patients can now use marijuana legally under federal law. The next step is for the executive branch of the federal government to move cannabis from Schedule One —drugs with no medical use and great potential for harm— to Schedule Three, so doctors can recommend it without fear of reprisal.”

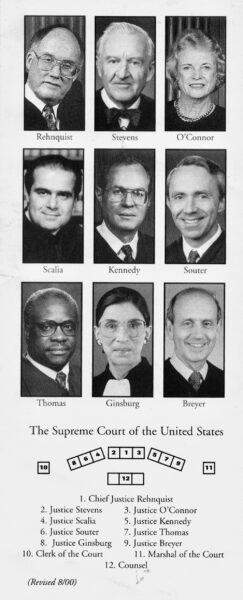

In 2000 the Justice Department asked the Supreme Court to reverse acceptance of the OCBC’s claim to a medical necessity defense. The case of the United States vs. the Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Cooperative and Jeff Jones was argued before the Supremes in March, 2001 by Gerald Uelmen, former dean of the Santa Clara University Law School (and a bit of a celebrity following his role on OJ Simpson’s defense team). Stephen Breyer, Charles’s older brother, recused himself. The ruling that came down in May was 8-0 against the OCBC, with Clarence Thomas writing the majority opinion. “A medical necessity exception for marijuana is at odds with the terms of the Controlled Substances Act,” they asserted.

But three liberal Justices —Ruth Bader Ginsburg, David Souder and John Paul Stevens— pointed out that the case was about distribution by a dispensary, not about individual patients. Their opinion noted, “This case does not call upon the court to deprive all such patients of the benefit of the necessity defense to federal prosecution.” The OCBC lawyers had presented ample evidence about individual patients with medical necessities, but these patients were OCBC members and were not parties to the case as individuals.

Uelmen told the Recorder, a San Francisco daily covering the courts, “The concurring opinion points out how narrow the ruling is on the merits. It only applies to distribution and manufacturing. I think there are still a lot of issues to be addressed.” The Recorder also reported, “District Attorney Terence Hallinan said the question of personal possession appears to be where some conflict my lie. ‘Possession would not be against California law, but it would be against federal law.'”

Robert Raich was not about to accept defeat. To help frame an argument that would sway the court’s majority —Scalia, Thomas, Rehnquist, Kennedy, and O’Connor— he enlisted a prominent libertarian law professor, Randy Barnett. In October 2002 they sought to enjoin the feds from raiding growers and patients operating legally under California law. The plaintiffs were Raich’s wife, Angel, who had been diagnosed with several life-threatening ailments; two anonymous growers who supplied her with marijuana; and Diane Monson, an accountant from Oroville who had grown six plants to treat her disabling back pain. The case was filed as Raich et al v Ashcroft et al. The plaintiffs’ key argument was that the federal government had no jurisdiction because the process by which the plants were grown for and consumed by them did not affect interstate commerce significantly.

“We expected Ginsburg and the other liberals to be against us,” Raich recalls, “but we thought we had a good chance of swaying the conservatives because in two recent cases, Lopez and Morrison, they had limited Congress’s power under the Constitution’s ‘Commerce Clause.'”

The key precedent was a 1942 case, Wickard v. Filburn, which established that impact on interstate commerce is not a function of individual transactions (such as caregivers growing cannabis for Angel Raich) but of all such transactions in aggregate (all medical users growing their own or having it grown for them within California).

Filburn was an Ohio farmer who grew more wheat than he was allowed to under the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which was intended to keep prices up by limiting production. That Act was clearly trying to regulate economic activity. The Court ruled that Congress could regulate consumption of Filburn’s wheat on his own farm because if all farmers acted likewise, Congress’s scheme to regulate the price would be undermined.

Raich-Monson argued that Wickard v. Filburn was a bad analogy because Filburn sold some of the wheat he raised, and much more of it was being consumed by his cows (from which he got milk, and which he sold occasionally) than by his family. Moreover, the Agricultural Adjustment Act didn’t apply to farmers growing small quantities for family use. And the principle of “aggregation” established in Wickard did not apply in the Lopez and Morrison cases by which the Rehnquist court had limited Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause.

By ruling against Raich and Monson, Barnett argued, the Court would significantly extend federal power under the Commerce Clause —the last thing “conservatives” supposedly want to do. If the court upholds the DOJ’s claim of federal power, Barnett warned, “this case will become the most expansive interpretation of the Commerce Clause since the Founding.”

During the oral argument, Justice Ginsburg —who’d had surgery for breast cancer and almost certainly knew people who had used marijuana for nausea and pain— asked if there had been any challenges to marijuana’s Schedule I status. Solicitor General Paul Clement whose reply noted that the Institute of Medicine had concluded “Whatever benefits there may be for the individual components in marijuana, smoked marijuana itself really doesn’t have any future as medicine” because the plant contains too many chemical components to evaluate.

Scalia commented, “I understand that there are some communes that grow marijuana for the medical use of all of the members of the commune… You can’t prove that they’re buying and selling. There are just a whole lot of people there with alleged medical needs.”

The plaintiffs’ strategy failed. Rob Raich recalls ruefully, “We expected Ginsburg and the other liberals to be against us. The power of the federal government under the Commerce Clause is something they really cared about. But for Scalia and Kennedy, their hatred of marijuana was a stronger salient issue than the centuries-old precedent of a necessity defense —stronger than their own recent precedents limiting Congress’s powers under the Commerce Clause.”