My heart leaped up as if I’d beheld a rainbow. The War on Drugs is not a Failure is a point a few under-the-radar journalists have been trying to make for years; it took Professor Hart to make it in the New York Times. (No news achieves “critical mass” in the US until it appears in the Times, Alex Cockburn observed. Even in this twittery era, it’s still the elite’s newspaper of record.)

Gone are the days when a hack writer could request and get review copies from book publishers. Begrudgingly, I paid online for “Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear” (Penguin, $28). While waiting for it, I emailed the Review a letter I knew they wouldn’t run:

In “Drug Use for Grown-Ups,” I learn from Casey Schwartz’s review, Carl Hart asks: what’s wrong with being a regular heroin user?

Her review is favorable, except for: “Hart’s writing can turn from passionate and moral to what feels like score-settling, undercutting the tenor of his narrative.”

I ask: what’s wrong with score-settling?

In 2011, Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance, explicitly and forcefully urged his followers to always describe the War on Drugs as a failure. (DPA would pay hundreds of activists to attend an annual conference at which Nadelmann laid out the party line.) Though supposedly a liberal, Nadelmann was a control freak, very strict about reformers “staying on message.” And because almost all activists and politicians craved some of the funding he doled out on behalf of George Soros (about $6 million annually), they made a mantra of “the failed war on drugs” in their speeches and blog posts. Google that awkward phrase to see how successful Nadelmann’s PR campaign has been.

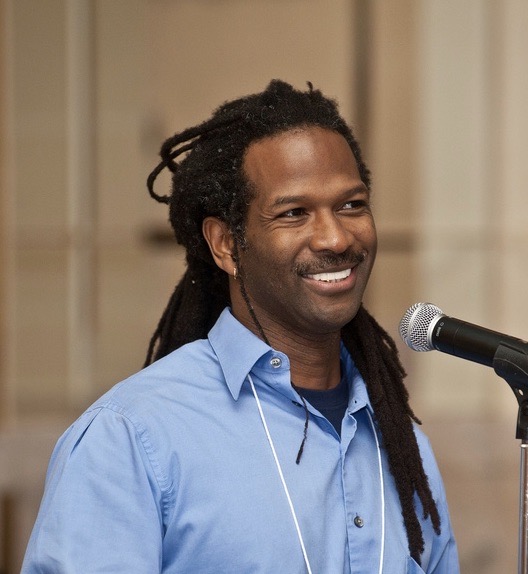

Hart, 54, was raised by his mother and her mother in the Black ghetto of Miami. He has close relatives in prison. He made his getaway by enlisting in the Air Force. He got a BA from the University of Maryland and a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Wyoming. He chose neuroscience, he says, because “It was clear to me that the poverty and crime in the resource-poor community from which I came was a direct result of recreational drug use and addiction. I reasoned that if I could stop people from taking drugs, especially by fixing their broken brains, I could fix the poverty and crime in my community.”

Columbia hired him as an associate professor of psychology in 1999. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) gave him millions in grant money. The university granted him tenure with alacrity. And all the while Hart considered illicit drug use harmful to the users and devastating for the Black community. His own research findings and observations over the course of a decade would lead him to reconsider. The book is dedicated, “For Parker and countless other real niggers —who shielded me from the hit, making it possible for a hood counterfeit to become mainstream legit.”

In the prologue Hart quotes Jefferson and adds, “I recognize that Thomas Jefferson and other revered historical figures enslaved Black people. This was reprehensible even during their time. But the cruel hypocrisy of these individuals’ actions does not negate the noble ideals and vision articulated in their writings.”

The Declaration of Independence, Hart reminds us, defines “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” as the inalienable rights of US Americans. So why, he asks, “Is our government arresting hundreds of thousands of Americans each year for using drugs, for pursuing pleasure, for seeking happiness?” The rationale for prohibition, he explains, is the chance of use leading to addiction:

“The conversation about recreational drug use is hijacked by peddlers of pathology as if addiction is inevitable for everyone who takes drugs. It is not. 70% or more of drug users – whether they use alcohol, cocaine, prescription medications, or other drugs – do not meet the criteria for a drug addiction. Indeed, research shows repeatedly that such issues affect only 10 to 30 percent of those who use even the most stigmatize drugs, such as heroin and methamphetamine. This observation highlights two important points. The first is society’s flagrant, disproportionate focus on addiction when discussing drugs. Addiction represents a minority of drug affects, but it receives almost all the attention, certainly the media attention… Imagine if you were interested in learning more about cars or driving and could only find information about car crashes or information about how to repair a car after a crash. That would be ridiculous.”

Hart has dreadlocks and is handsome as any rock star. It’s hardly surprising that reviews of “Drug Use for Grown-Ups” focus on his first-person revelations. “I am now entering my fifth year as a regular heroin user,” he acknowledges. “I do not have a drug problem. Never have. Each day, I meet my parental personal and professional responsibilities. I pay my taxes, serve as a volunteer in my community on a regular basis, and contribute to the global community as an informed and engaged citizen.” Hart doesn’t fix; he does lines of heroin (and ingests other opioids). He sees his use pattern as typical. “Research clearly shows that most heroin users are people who use the drug without problems, such as addiction; they are conscientious and upstanding citizens.”

The chapters on amphetamines, psychedelics, cannabis, cocaine, and “novel psychoactive substances” also combine Hart’s first-hand observations with the relevant published research, and are replete with citations that should satisfy the academic without breaking the flow of his very readable narrative.

Mitch Twists Hart’s Gist

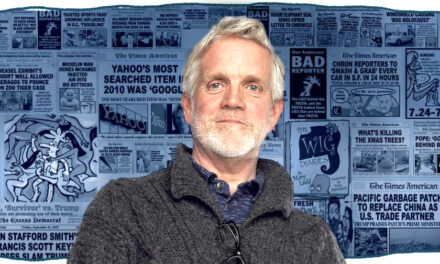

Exactly as Carl Hart foresaw, “peddlers of pathology” are raising the specter of addiction in an attempt to discredit his thesis. The February 7 Times Book Review ran a letter by Mitchell S. Rosenthal, owner of the Phoenix House chain of treatment centers, dissing Hart’s book and promoting his own business. In closing, Rosenthal wrote, astonishingly, “I agree with Hart that the ‘war on drugs’ has failed, but his war on the reality of addiction is far more dangerous.” Two weeks earlier the Times had run a review stating that Hart disputed the notion that the War on Drugs has been a failure. Rosenthal was “agreeing” with the opposite of Hart’s important point! You’d think an editor would have consulted the book itself to confirm that their reviewer had it right —she did—and then rejected Rosenthal’s letter or respectfully asked him to cut the shit.

Rosenthal’s letter was doubly duplicitous. By pretending to agree with Hart, the treatment magnate tries to come off as a reasonable, unprejudiced man, when in fact he is biased and self-serving. If and when there’s ever a decline in the number of US drug users mandated to get “treatment” by courts, employers, schools and others in position of authority, Mitch Rosenthal’s Phoenix House empire will lose revenue.

Pardon me while I settle a score. In the spring of 1996 the New Yorker assigned me to write a piece about Proposition 215, the ballot initiative to legalize marijuana for medical use in California. The piece was scheduled to run the week before the November 4 election or the week after. It was spiked at the last minute, according to my editor, Hendrik Hertzberg, at the urging of “Tina’s guru on drug issues, Mitch Rosenthal.” Tina Brown was the top editor at the NYer. Rosenthal’s Phoenix House had taken in millions of dollars thanks to marijuana prohibition. The Village Voice ran a much-shortened version of my Prop 215 piece on November 12 and the New Yorker sent a $3,000 ‘kill fee’ —a lot more than I’d ever been paid for magazine articles that actually got published.

When US Drug Czar Gen. Barry McCaffrey retired in 2000 at the end of Bill Clinton’s term, he went to work for Rosenthal pitching “treatment” as an alternative to incarceration.

The Harm in ‘Harm Reduction’in

The Wall St. Journal ran a review of Drug Use for Grown-ups by Dr. Sally Satel that actually was fair and balanced. Unfortunately, Satel inverted one of Hart’s key points just as Rosenthal had done in the Times. “As a psychiatrist,” she wrote, “I know that some people can be responsible users of even the most feared drugs. But the pill mills of Appalachia and the needle-strewn streets of San Francisco show how devastating unfettered access to drugs can be. Mr. Hart promotes treatment and harm reduction (e.g., clean needles, safe-injection rooms, testing for contaminants), but he doesn’t offer a detailed blueprint for keeping drugs away from the people whose lives can be ruined.”

Hart acknowledges up front that his book is not about addiction, it’s about drug use by responsible adults in pursuit of happiness. The treatment industry is run by the very “peddlers of pathology” who Hart says have “hijacked the conversation about recreational drug use.” Thinking I may have missed his discussion of treatment, I checked the index. It lists “tolerance, Trainspotting (movie), triazolam…”

The index lists seven aspects under harm reduction: “drug safety testing, fentanyl scare, letting it go, opioid crisis, Park Life festival, replacing the term, use of the term.” The index lists seven aspects under harm reduction: “drug safety testing, fentanyl scare, letting it go, opioid crisis, Park Life festival, replacing the term, use of the term.” How did Satel mistake Hart’s assessment of harm reduction?

Hart defines the term as “an attempt to reduce negative consequences associated with drug use. Providing clean needles and syringes to an intravenous heroin user is an example of harm reduction because it decreases the person’s chances of contracting a blood-borne infection from sharing contaminated injection equipment. Instructing a festival-goer to drink lots of fluids, to stay well hydrated, if the individual takes a diuretic drug such as MDMA or methamphetamine, is another example of harm reduction…”

Then he explains why he deplores the term: “Each one of us on a daily basis takes measures to prevent illness and to improve our health and safety: we brush our teeth, wear seatbelts, use condoms, exercise. We don’t call it harm reduction, we call it common sense, prevention, education, or some other neutral name… The term harm reduction is used almost exclusively in connection with drug use and has negative connotations… [It] preoccupies us with drug-related harms. The connection between harms and drug use is reinforced repeatedly through our speech. This connection in turn narrows our associations, conversations, feelings, memories, and perceptions about drugs and those who partake. Perhaps even worse, it relegates drug users to an inferior status. Surely, only a feeble-minded soul would engage in an activity that always produces harmful outcomes, as the term implies.”

A scholarly paper on the origins of the term “harm reduction” appeared in Critical Public Health September 2005. According to author Gordon Roe, a professor at Simon Fraser University, “The story begins with the activists, workers, doctors, programs and policymakers committed politically and socially to opposing the legal suppression of drug use and the oppression of drug users in the 1960s and 70s. In the mid-1980s these alternatives began to be referred to collectively as part of the ‘risk reduction,’ ‘harm reduction,’ and ‘harm minimization’ solution to the health problems of HIV/AIDS amongst injecting drug users. Harm reduction has since become identified also with addictions treatment…”

In the medical marijuana movement the phrase “harm reduction” was pushed forcefully and for years by the Influencer of Influencers, Ethan Nadelmann of the Drug Policy Alliance. Dr. Tod Mikuriya, the co-founder of O’Shaughnessy’s, used the term uncritically and I disseminated it. I vaguely sensed that there was something opportunistic about “harm reduction;” Carl Hart’s elucidation of the term showed me how and why.