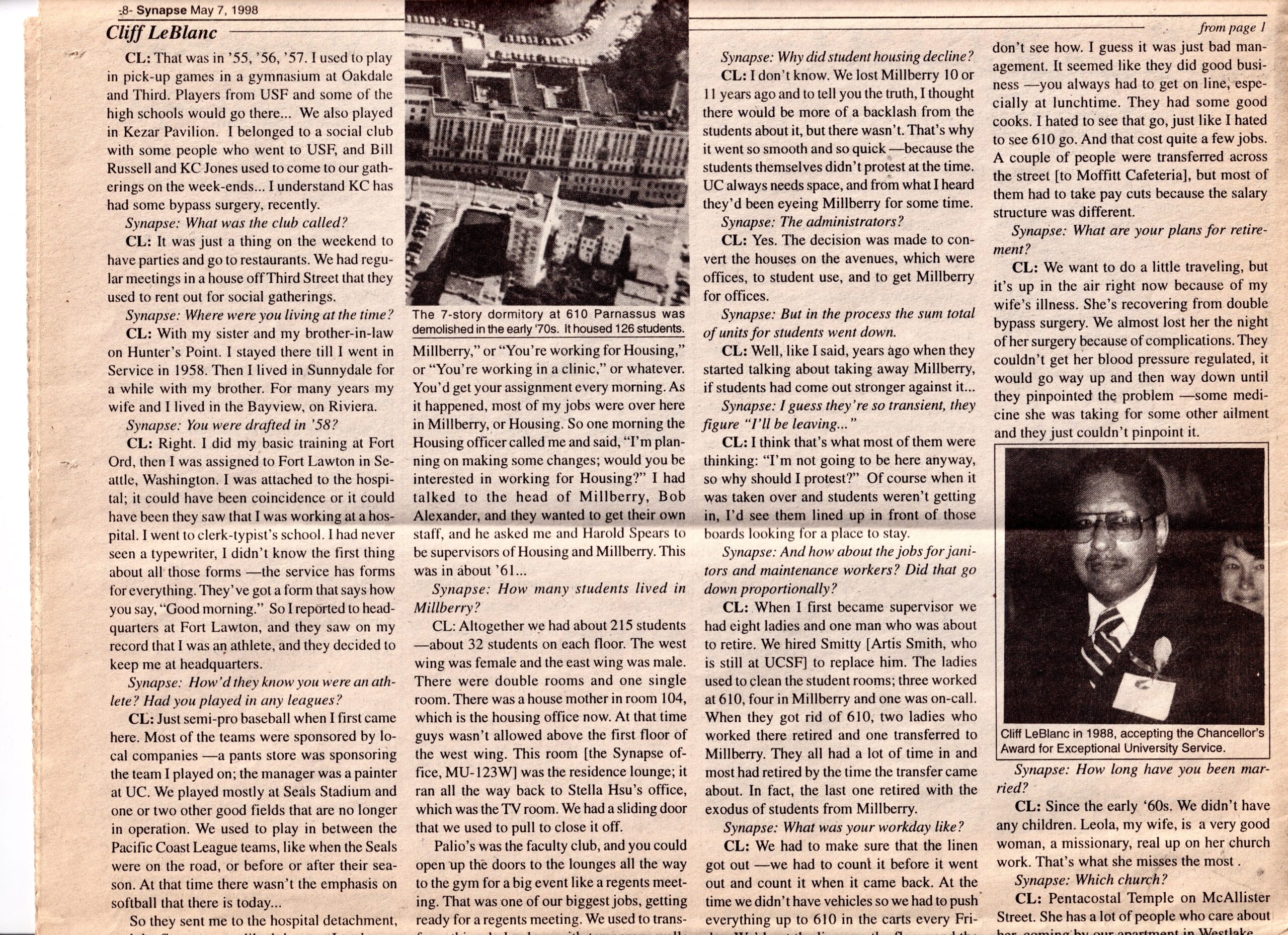

UCSF Medical Center is the largest employer in San Francisco besides the city and county itself. Cliff LeBlanc worked there for more than 42 years, retiring in 1998. He was calm, amiable, very knowledgable about how things worked. I knew that he was from the south and that KC Jones and Bill Russell used to call him when they were in town. Looking back in an interview for Synapse, the campus weekly, LeBlanc had some revealing things to say about how conditions had changed for employees and students during his years at UCSF. (In those days the campus was on Parnassus Heights in the Inner Sunset district. The big Mission Bay expansion was on the drawing boards.)

Synapse: What brought you to San Francisco originally?

Cliff LeBlanc: I first came out here in 1953 to bring my nephew from Donaldsonville, Lousiana. His father had just gotten out of the Navy. He was one of those stationed at Port Chicago [a Naval ammo base on San Francisco Bay] and his wife was out here with him. So at the end of the school year I brought my nephew out here, with the intention of going hack to Louisiana after a while. But I got a job at a service station, and decided to stay.

Donaldsonville was a small town about 60 miles south of New Orleans. The Mississippi River runs through it. At the time there was no jobs or opportunities, but that’s changed since then, there are all these different plants down there. I couldn’t foresee that… We had a family of 11: eight brothers and two sisters. I have four brothers that’s passed and one sister that’s passed. All but one are retired and are living in Clear Lake. Me and my baby brother Claudel are the only ones still living in San Francisco. He’s been working at Laguna Honda as head of the Inhalation Department. He’s also in real estate. I only have two nieces and a nephew left in Donaldsonville…

Synapse: Was your brother-in-law at Port Chicago when the explosion took place? [In July, 1944, 320 Navy personnel were killed and 390 wounded when the ammunition they were loading onto a ship exploded. The survivors subsequently refused to load ammo without proper training —and were court-martialed. All the ammo loaders were black and all the officers were white.]

CL: He was one of the men who got thrown off the boat. His feet got burned. He was never quite right after that… They ordered them to load live ammo and they knew it was a danger. There were certain ways to handle it, certain procedures, but they had never been told how to handle it, and half the time they weren’t told what they were handling. The officers would just say, “Move this from here to there.” And somebody did something wrong and the thing just blew up. A lot of them got maimed, killed. And then they were prosecuted!

Synapse: Did that injustice ever get reversed?

CL: Every so often some old-timers will protest, but that’s about it.

Synapse: How did you come to work at UCSF?

CL: It was March of ’56 and I had just turned 19. At the time I was working long hours at a service station–opening at 7 in the morning and closing at midnight, six days a week and sometimes on Sundays, too. I was just out here one day to see by brother-in-law, Lloyd McKenny, who was a janitor at the time. I was sitting on the General Serves’ messengers bench. I saw a lot of guys in little gray jackets running in and out. I didn’t know what was going on. Suddenly all of ’em disappeared, and the dispatcher was hollering “Messenger! Messenger! Messenger!” and no one responded and the calls were piling up. So the supervisor, Bert Cook, told her to call in the janitors and the window washers, but still the calls were piling up. So he come out and I was just sitting there reading the paper, and he said “Who are you?” I told him I was Lloyd’s brother-in-law and he said, “You want a job?” I thought he was kidding, but he wasn’t. He told the dispatcher, “Call Personnel, tell `em we’re sending over a new employee.” And he wrote me out a messenger slip to take over to Personnel, which was in the basement of UC [Hospital] at the time. [Personnel is now called “Human Resources” and located in the Laguna Honda School building on 7th Ave.] They had my papers ready and it took about 15 minutes to sign me up… I went back and they started giving me calls right away. Half the time I didn’t know where to go, but they

told me and I learned.

Synapse: What was General Services?

CL: At that time General Services did everything. Specimens, X-rays, whenever a patient had to be moved, it was through General Services. Now most of the departments take care of that themselves. Moffitt and then the Medical Sciences building opened around the same time in the mid-50s. At that time the swimming pool was in UC [Hospital] for physical therapy patients. so you’d bring patients there. You’d bring patients to Langley Porter, which is where

they did neurosurgery at the time. You’d pick up and bring specimens to the lab. The metabolic lab was a little shack where the library is now and Dr. Peter Forsham was in charge of it…

Synapse: How did you meet Bill Russell and KC Jones?

CL: That was in ’55, ’56, ’57. I used to play in pick-up games in a gymnasium at Oakdale and Third. Players from USF and some of the high schools would go there… We also played in Kezar Pavilion. I belonged to a social club with some people who went to USF, and Bill Russell and KC Jones used to come to our gatherings on the week-ends… I understand KC has had some bypass surgery, recently.

Synapse: What was the club called?

CL: It was just a thing on the weekend to have parties and go to restaurants. We had regular meetings in a house off Third Street that they used to rent out for social gatherings.

Synapse: Where were you living at the time?

CL: With my sister and my brother-in-law on Hunter’s Point. I stayed there till I went in Service in 1958. Then I lived in Sunnydale for a while with my brother. For many years my wife and I lived in the Bayview, on Riviera.

Synapse: You were drafted in ’58?

CL: Right. I did my basic training at Fort Ord, then I was assigned to Fort Lawton in Seattle, Washington. I was attached to the hospital; it could have been coincidence or it could have been they saw that I was working at a hospital. I went to clerk-typist’s school. I had never seen a typewriter, I didn’t know the first thing about all those forms —the service has forms for everything. They’ve got a form that says how you say, “Good morning.” So I reported to head-quarters at Fort Lawton, and they saw on my record that I was an athlete, and they decided to

keep me at headquarters.

Synapse: How’d they know you were an athlete? Had you played in any leagues?

CL: Just semi-pro baseball when I first came here. Most of the teams were sponsored by local companies —a pants store was sponsoring the team I played on; the manager was a painter at UC. We played mostly at Seals Stadium and

one or two other good fields that are no longer in operation. We used to play in between the Pacific Coast League teams, like when the Seals were on the road, or before or after their season. At that time there wasn’t the emphasis on

softball that there is today.

So they sent me to the hospital detachment and the first sergeant liked the way I took care of the flower garden in front of the day room, and he made me company clerk… I also got a job working at the NCO club in the evenings as a short-order cook and bartender. If I didn’t have any week-end duty, I would come home to San Francisco on Friday nights.

I would get a military hop [flight]. You know, everybody’s the company clerk’s best friend because he controls their destiny. They used to send a levee down every week for people to go to different parts of the country, or to Korea. They would tell you how many privates they wanted, how many lieutenants, how many sergeants, and I would go down the list and check `em off. So every Friday without fail, the guy who was in charge of the hops would call me, “Want to go this week’?…” And I’d say, “Well, I don’t have anything planned up-here…” So I’ve had some pretty good breaks along the way.

Synapse: But you didn’t re-up.

CL: They tried. “I guarantee you’ll get a $10,000 bonus and you’ll get to stay here.” But I knew enough about the Army to know that nobody can guarantee you anything. And Vietnam was beginning to act up, so I said “No.”

Synapse: And then you came back to UC?

CL: Well, I had enough money saved up so I thought, “Why go back to work right now?” But I got back on a Thursday and first thing that Monday morning the dispatcher called and said, “When are you coming back to work? We need you.” So I came right back to work. My younger brother had gotten a job here with General Services, and when I came back they had to find him another position. At that time UC didn’t let you go —they had to have a real good reason to terminate you from any job, so even though he was in there temporarily, they had to find him another job. They gave him a job in Inhalation Therapy and I went back as a messenger and after about six months this man named Walsh offered me a job as a janitor at $2 an hour. As a messenger I was making $1.27 an hour. [Minimum wage then was 95¢.]

So I became a janitor. At that time you’d report to General Services and they would tell you, “You’re working in Millberry,” or “You’re working for Housing,” or “You’re working in a clinic,” or whatever. You ‘d get your assignment every morning. As it happened, most of my jobs were over here in Millberry, or Housing. So one morning the Housing officer called me and said, “I’m planning on making some changes; would you be interested in working for Housing?” I had talked to the head of Millberry, Bob Alexander, and they wanted to get their own staff, and he asked me and Harold Spears to be supervisors of Housing and Millberry. This was in about ’61…

Synapse: How many students lived in Millberry?

CL: Altogether we had about 215 students about 32 students on each floor. The west wing was female and the east wing was male. There were double rooms and one single room. There was a house mother in room 104, which is the housing office now. At that time guys wasn’t allowed above the first floor of the west wing. This room [the Synapse office, MU-123W] was the residence lounge; it ran all the way back to Stella Hsu’s office, which was the TV room. We had a sliding door that we used to pull to close it off. Palio’s was the faculty club, and you could open up the doors to the lounges all the way to the gym for a big event like a regents meeting. That was one of the biggest jobs: getting ready for a Regents meeting. We used to transform this whole place with temporary walls to make different entrances for security purposes. We used to house the governor in the guest suite on the second floor of the east wing. We had four guest suites on that floor they had the whole floor.

Synapse: Governor Pat Brown?

CL: Pat Brown and then Ronald Reagan. In Reagan’s time you had Haight Street and the students at Poly [Polytechnical High School on Frederick St.], so it was a powder keg up here. You didn’t have everything locked

up as it is now; everything was open. So when the regents came, we had to put up partitions and there were certain doors that had to lock.

Synapse: Was there housing for other students —in addition to the 215 at Millberry?

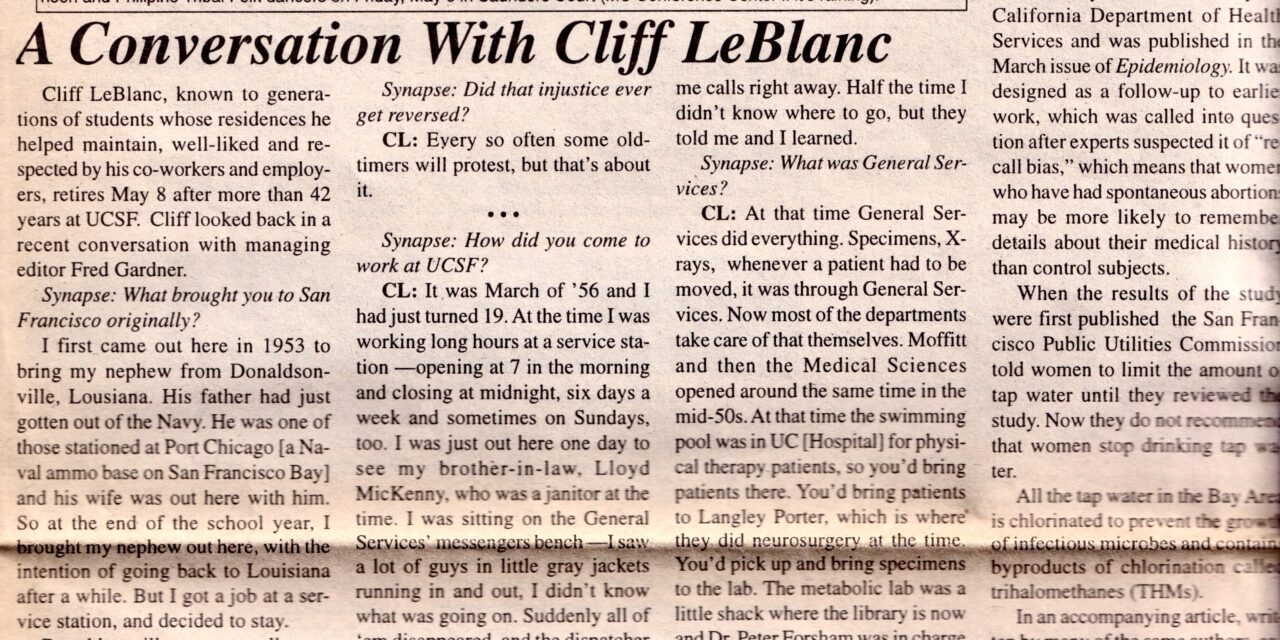

CL: We had 126 students at the residence building at 610 Parnassus. We just called it “610.” It started out just women, mainly nurses. When things started loosening up in the late ’60s, they made it co-ed and one floor was women and one floor was men and so on. They tore it down because they said it wasn’t earthquake proof, but I thought that was the most sturdy building on campus. I said “I’d rather be caught in 610 than in Millberry.” I actually loved that’ building. It was steel frame, with stucco. On the first floor was the house mother’s apartment, and she had a desk facing the elevator. You had to check in with her first, and she would call up and say “You have a guest,” and that’s what the lounge was for… Students were on [floors] 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, mostly singles and a few doubles. The seventh floor had an auditorium, study rooms, piano rooms, a kitchen. It was real nice. The only thing the students didn’t like was the community bathrooms.

Synapse: So at one point UCSF provided housing for 341 students.

CL: More than that. We had Aldea. And one house on the avenues -1350 Third Avenue. We also had the apartment house on Irving St. [145 Irving], which was a residence for married students. I think they had eight apartments in that building.

Synapse: Why did student housing decline?

CL: I don’t know. We lost Millberry 10 or 11 years ago and to tell you the truth, I thought there would be more of a backlash from the students about it, but there wasn’t. That’s why it went so smooth and so quick —because the students themselves didn’t protest at the time. UC always needs space, and from what I heard they’d been eyeing Millberry for some time.

Synapse: UC meaning the administrators?

CL: Yes. The decision was made to convert the houses on the avenues, which were offices, to student use, and to get Millberry for offices.

Synapse: But in the process the sum total of units for students went down.

CL: Well, like I said, years ago when they started talking about taking away Millberry, if students had come out stronger against it…

Synapse: I guess they’re so transient, they figure “I’ll be leaving…”

CL: I think that’s what most of them were thinking: “I’m not going to be here anyway, so why should I protest?” Of course when it was taken over and students weren’t getting in, I’d see-them lined up in front of those housing boards looking for a place to stay.

Synapse: And how about the jobs for janitors and maintenance workers? Did that go down proportionally?

CL: When I first became supervisor we had eight ladies and one man who was about to retire. We hired Smitty [Artis Smith, who is still at UCSF] to replace him. The ladies used to clean the student rooms; three worked at 610, four in Millberry and one was on-call. When they got rid of 610, two ladies who worked there retired and one transferred to Millberry. They all had a lot of time in and most had retired by the time the transfer came about. In fact, the last one retired with the exodus of students from Millberry.

Synapse: What was your workday like?

CL: We had to make sure that the linen got out —we had to count it before it went out and count it when it came back. At the time we didn’t have vehicles so we had to push everything up to 610 In the carts every Friday. We’d put the linen on the floors and the ladies would bring it to the rooms. We didn’t have carpets; we had a lot of tile floors which we had to strip and wax and buff. It was a full day. We didn’t do big maintenance but we did unstop toilets and change light bulbs, that level of maintenance. All day long there was some- thing going on.

Synapse: Who handled the big jobs?

CL: Physical plant. At that time they had a full maintenance crew.

Synapse: How about nowadays?

CL: They have one full-time maintenance and two 60-40 custodian-and-maintenance., Smitty is 50-50 and I was 50-50 while I was working. Oswaldo Robelo is the main maintenance guy. If there’s a big sewer problem we’ll call Malcolm Plumbing or Roto-Rooter.

Synapse: When did you switch from Housing to Millberry?

CL: I never switched. I just added Millberry at some point in the late ’60s. It was supposed to be 75 percent of my time, but sometimes it was 50-50 or even 75-25, because we had a lot of events going on in Millberry. Then Housing demanded more of my attention…

About five or six years before Millberry closed down [as student housing], they made changes and we cut back on the service we provided. We’d just clean the guest suite and, just like now, we’d clean the public areas, and we’d clean the showers and bathrooms. We had two ladies on each side used to do those functions. And we’d clean out the kitchens

they had a kitchen on each floor.

Synapse: In addition to the big cafeteria on I-level?

CL: Yes. Originally they had lounges at the end of every floor; then, when they made the cafeteria smaller, they converted the lounges into kitchens for the students… The cafeteria went from where the juice bar and Sports Medicine is now, all the way back to the swimming pool. It was real big and it was always crowded.

Synapse: It was plenty busy when I got here in ’87. Why did that cafeteria fail?

CL: Well, they said it was losing money. I don’t see how. I guess it was just bad management. It seemed like they did good business —you always had to get on line, especially at lunchtime. They had some good cooks. I hated to see that go, just like I hated to see 610 go. And that cost quite a few jobs. A couple of people were transferred across the street [to Moffitt Hospital Cafeteria], but most of them had to take pay cuts because the salary structure was different.

Synapse: What are your plans for retirement?

CL: We want to do a little traveling, but it’s up in the air right now because of my wife’s illness. She’s recovering from double

bypass surgery. We almost lost her the night of her surgery because of complication. They couldn’t get her blood pressure’ re ulated, it would go way up and then way down until they pinpointed the problem —some medicine she was taking for some other ailment and they just couldn’t pinpoint it.

Synapse: How long have you been married?

CL: Since the early `60s. We didn’t have any children. Leola, my wife, is a very good woman, a missionary, real up on her church work.That’s what she misses the most.

Synapse: Which church?

CL: Pentacostal Temple on McAllister Street. She has a lot of people who care about her coming by our apartment in Westlake.

Synapse: I’m sure everybody here is wishing her well, too. Here’s to a long, happy retirement, Cliff.. Any final comments about

how UCSF has changed over the years?

CL: Well, it used to be more like a family affair where everybody knew everybody. We’d have get-togethers. The difference today is, you don’t have that. I don’t want this to come across wrong but… [long pause]

Synapse: A colder, more bureaucratic atmosphere?

CL: You said it right. It’s more of a business now. You know. Not that people want it to be like that; they’re just driven that way. You get an order, you’ve got to do it that way. It’s not like it used to he. It really used to be a fun place to work. It still is in some places, but it’s not geared to the employee now.

Synapse: It used to be you’d tell someone you worked at UCSF and they’d say “Lucky you!”

CL: That’s right, everybody would say “Could you get me a job there?” ‘Cause at one time there was no such thing as a lay-off. Nowadays you never know what’s going to happen. You never know when they’re going to say, “Well, we’re going to get rid of this department or downsize this.” In those days you didn’t ever hear that kind of talk. But nowadays you’ve got to be looking out for it at all times. Nobody’s safe, no position; that’s the biggest difference. Just look at the merger, things like that. I know they have their own reasons, and we might as well face it, the reasons come down to the bottom line. But like I said, they can say, “We’re going to make this change next month and we’ll try to find you a job…” And maybe they will and maybe they

won’t.

Synapse: Cliff, I know I’m speaking for a lot of people when I say that you’ll really be missed. You care about this place and about the students. I hope some youngster applying for a job today gets to have a Iong career and can retire in 2000-something with security and dignity.

By an odd coincidence, the day after I filed this piece with the Anderson Valley Advertiser, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a front-page story about “the Port Chicago 50.” Cliff had that right, too… The deterioration of “healthcare” in the US is not some recent trend. As LeBlanc pointed out back in ’98, UCSF Administrators had been cutting back on workers who kept the place clean –janitors, housekeepers, orderlies… “Orderly” is one of those meaningful words that has been replaced in our time by a more politically correct phrase. According to Wikipedia, “In the US, orderlies have been phased out of health care facilities in recent years and their functions are now replaced by the patient care assistant and Certified Nursing Assistant. They remain common in Canada and other countries.” (Countries that happen to have much lower maternal death rates, etc.)… I just added orderlies to our list of Two words when one will do

–Fred Gardner